calsfoundation@cals.org

Extinct Animals [Prehistoric Period]

Fossils and sedimentary rock layers contribute to current knowledge of the animals that lived in Arkansas in the geologic past. A careful examination of these layers and the types of fossils contained in them reveals clues about the age of the rock and the different environments of the past. In the older deposits, evidence indicates that all of Arkansas was covered by the ocean at various times; fossils of marine animals are found as well as sequences of rock that display patterns only found in marine sedimentary deposits. In some of the most recent deposits, the remains of land animals that walked the earth just a few thousand years ago have been found. All but the most recent of the fossils are of extinct animals.

Animal species may become extinct for several reasons. The most prosaic reason is simple evolution. All animals evolve enough over long time intervals to be considered different species by modern taxonomists. Because the fossil record is often incomplete, researchers may lack many of the transitional steps between one recognized species and its direct descendant. In a sense, a species like this does not really go extinct—it just evolves into something else. All living creatures are examples of this.

Extinction that leaves no descendants, however altered, occurs quite commonly in the geologic record. This can be due to changes in the physical environment, competitive interaction with one or more other species, pure chance, or a combination of these circumstances. Climate change is a major environmental driver of evolution and therefore, extinction. If the climate of the home range of a species changes faster than the species can evolve or move away from, the species may die out completely. Invasion of predators into a region not previously occupied by them can dramatically impact certain species unprepared to deal with the new threat. A species that has co-existed with another may evolve some new ability that gives it a significant advantage over the other species. In time, it may supplant the less capable species through better or more aggressive utilization of the resources they both need for success. Species populations fluctuate normally. If a species is composed of a small population, a chance reduction in numbers may reduce the population to below some critical number necessary for continued existence. In general, species that evolve specializations to utilize some restricted resource or living space are more at risk of extinction than creatures that are generalists. In modern times, habitat destruction or alteration and introduction of foreign species brought about by anthropic means tend to occur at a high rate as compared to the pace of most natural systems, driving the extinction process at an accelerated tempo.

The rate of species extinction seems to have been fairly stable throughout geologic history. A few times in geologic history, however, the earth has experienced global catastrophes that have resulted in the extinction of significant percentages of the planet’s species. During the Late Ordovician Period (about 450 million years ago), at the end of the Paleozoic Era (about 248 million years ago), near the Triassic-Jurassic Periods boundary (about 206 million years ago), and at the end of the Cretaceous Period (about 65 million years ago), events occurred that caused the extinction of between forty percent and ninety percent of all species living at the time. Different theories have been put forth to suggest why these global extinction events occurred, and it now seems clear that several mechanisms may have been at work. For example, the extinction event at the end of the Cretaceous Period is widely thought to have been largely caused by a significant asteroid impact on the Yucatan Peninsula of Mexico.

The history of now extinct animal life in Arkansas, as evidenced by the fossils, ranges from over 500 million years ago to as recently as 1,000 years ago. Throughout that time, the state has undergone many changes. Five hundred million years ago, all of the state was beneath an ocean and south of the equator. Arkansas was on the margin of the early “North American” continent before it acquired the southeastern part. For hundreds of millions of years, sea level rose and fell, sometimes exposing parts of Arkansas to erosion—which removed thick sequences of rock and their encased fossils—and at other times allowing deposition of sediments with the animal remains on an ocean bed that would one day be the layers of rock and fossils found in modern times. About 250 million to 300 million years ago, what was to become the southeast and southern part of the continent converged with the rest and uplifted the portions now called the Ozarks and the Ouachitas. Oceans continued to cover portions of the state, however, until just the last few million years. Most recently, the glacial-interglacial cycles have left their traces.

The fossils do not represent all of the animal life of a particular time in earth’s history—only the remains that survived. Soft tissue decays easily and rarely gets preserved. Animals without hard parts such as shells, bones, and/or teeth are poorly represented in the fossil record. Even these hard parts do not survive if they are not quickly removed from the destructive processes of the earth’s surface. Generally, rapid burial is needed to preserve a fossil, and this happens most often in a marine environment. Therefore, most of the record of past animal life is of marine animals.

The oldest fossils found in Arkansas are of simple ocean creatures that lived during the early part of the Paleozoic Era, about 500 million years ago. Microscopic single-cell plants and animals created sediment-trapping structures called stromatolites in the shallow waters of northern Arkansas. Macroscopically, trilobites—a group of arthropods—held dominance over all other macroscopic life for tens of millions of years. Later, their numbers declined as ecosystems became more complex, extinction events took their toll, and other marine creatures became better adapted to compete for food and living space.

Brachiopods, mollusks (snails, bivalves, cephalopods, etc.), corals, crinoids, bryozoans, and graptolites supplanted the trilobites as the dominate life forms on the planet. They went on to dominate the marine macroscopic life for the next four geologic periods (through the end of the Paleozoic Era, about 240 million years ago). Their fossils are found in abundance in certain rocks, mostly in the Ozark region. The most common fossil found in the state is of the crinoid, an animal related to starfish and sea urchins. The crinoid is sometimes called a sea lily because of its plant-like appearance. The generalized crinoid has a root-like structure called a holdfast that anchors it to the sea floor. Arising from the holdfast is a long stem of disk-shaped sections. Capping the stem is a cup-shaped head with branching arms radiating from it. The animal spreads its arms into the currents and filters plankton for its food. Its skeleton is composed of calcium carbonate in the mineral form calcite. The broken skeletons of crinoids make up most of the recognizable sediment particles that compose Arkansas’s limestones. In one sense, the high limestone bluffs along northern Arkansas rivers are merely ground-up “seashells” cemented together.

At the beginning of the Mesozoic Era (240 to 65 million years ago), an ocean covered half of the state. Little evidence exists of the creatures that lived in the early part of the Mesozoic because of the lack of exposed rocks formed during that time, but deposits of the Cretaceous Period, the last period of the Mesozoic, are exposed in southwestern Arkansas, just south of the Ouachita Mountains. These sediments mainly represent shallow to marginal marine environments, with a few near-shore terrestrial deposits. This was the time of the so-called “ruling reptiles.” Single-celled foraminifera and tiny crustaceans called ostracods dominated the microscopic fauna. The macroscopic invertebrate remains include oysters and other bivalves, snails, cephalopods, corals, worms, barnacles, echnoids, and crabs. The remains of turtles, sharks, and sawfish, as well as other fish, crocodiles, plesiosaurs, and mosasaurs are among the marine vertebrates. The plesiosaur was a large paddle-finned reptile, and the mosasaur was a large marine lizard that looked somewhat like a crocodile.

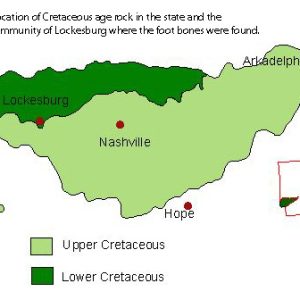

On land, dinosaurs left few fossils. A right hind foot of a long-necked, bipedal, coelurosaur named “Arkansaurus fridayi” was found in Sevier County in 1972. In 1983, a trackway of thousands of footprints of various sauropods (large, quadrupedal, vegetarian dinosaurs) was discovered in Howard County.

Tertiary Period deposits (65 to 1.8 million years old) are made up of the usual marine invertebrate microscopic faunal groups, the foraminifera and ostracods, as well as a macroscopic fauna of oysters and other bivalves, snails, cephalopods, and crabs. The marine vertebrates include sharks, rays, and catfish, as well as other fish, whales, snakes, and turtles. Crocodiles still roamed the shoreline and swamps. One unique Tertiary terrestrial deposit found in southwestern Arkansas preserves an occasional insect or spider in amber (fossil tree sap).

By the Pleistocene Period, the oceans had receded from Arkansas. The fossils we find represent the climatic influences of the Ice Age. Most of the fossils of this age are preserved in cave or stream deposits. In 1903–04, the American Museum of Natural History excavated Conard Fissure, a sinkhole cave in northern Arkansas. Remains of fifty-one mammal species, seven amphibian and reptile species, and seven species of birds were found. Included were several extinct and extant species. Among the extinct animals were certain species of shrew, bat, skunk, weasel, lynx, saber-tooth cat, chipmunk, gopher, mouse, muskrat, horse, peccary, and musk ox. Other cave and bluff shelter deposits have included many of these groups and added dire wolf, mammoth, mastodon, elk, and armadillo to the recently extinct species list. Stream deposits in various places around the state have yielded many of the same species, including a few not yet found in other places in Arkansas, such as a giant ground sloth and a beaver. Some of these creatures have gone extinct quite recently, in ages that overlap very early historical times.

For additional information:

“Geologic Time Scale v. 5.0” Geologic Society of America. https://www.geosociety.org/documents/gsa/timescale/timescl.pdf (accessed August 19, 2023).

Brown, Barnum. “The Conard Fissure, a Pleistocene Bone Deposit in Northern Arkansas: With Descriptions of Two New Genera and Twenty New Species of Mammals.” Memoirs of the American Museum of Natural History 9.4 (1908): 157–208.

Davis, Leo Carson. “The Biostratigraphy of Peccary Cave, Newton County, Arkansas.” Proceedings of the Arkansas Academy of Science Proceedings 23 (1969): 192–196

Freeman, Tom. “Fossils of Arkansas.” Bulletin 22. Little Rock: Arkansas Geological Commission, 1966, p. 53.

McFarland, John David. “Stratigraphic Summary of Arkansas.” Information Circular 36. Little Rock: Arkansas Geological Commission, 2004.

Pittman, Jeffrey G., and David D. Gillett. “Tracking the Arkansas Dinosaurs.” Special issue, The Arkansas Naturalist 2 (March 1984).

Quinn, James H. “Arkansas Dinosaur.” In Geological Society of America Abstracts with Programs for 1973. Boulder, CO: Geological Society of America, 1973.

———. “Extinct Mammals in Arkansas and Related C14 Dates Circa 3000 Years Ago.” In Proceedings of the 24th International Geological Congress. Montreal, Canada: International Geological Congress, 1972.

John David McFarland

Arkansas Geological Survey

"Arkansaurus fridayi"

"Arkansaurus fridayi"  Arkansaurus fridayi Territory Map

Arkansaurus fridayi Territory Map  Mastodon Display

Mastodon Display  Mastodon Femur

Mastodon Femur

Comments

No comments on this entry yet.