calsfoundation@cals.org

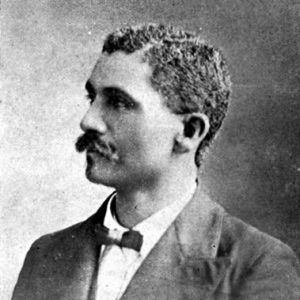

Elias Camp Morris (1855–1922)

Elias Camp Morris was an African American minister who, in 1895, became president of the National Baptist Convention (NBC), the largest denomination of Black Christians in the United States. Recognized by white Arkansans and the nation as a leader of the Black community, he often served as a liaison between Black and white communities on both the state and national level. He was also an important leader in the Arkansas Republican Party.

Morris was born in slavery on May 7, 1855, in Murray County, Georgia, the son of James and Cora Cornelia Morris. In 1864–1865, he simultaneously attended grammar schools in Dalton, Georgia, and Chattanooga, Tennessee. From 1866, he attended school in Stevenson, Alabama, and in 1874–1875, he attended Nashville Normal and Theological Institute (renamed Roger Williams University in 1883) in Nashville, Tennessee. From 1872 to1886, he worked as a shoemaker. In 1874, he was licensed to preach in a Baptist church. In 1877, attracted by opportunities in the western states, he set out for Kansas but chose to settle in Helena (Phillips County) instead.

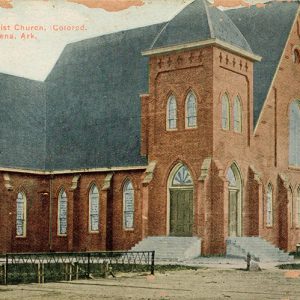

In Helena, Morris pursued careers in politics and the church. In 1879, he became an ordained Baptist minister and pastor of Centennial Baptist Church, while also organizing the Phillips, Lee, and Monroe counties’ Black Baptist association. From 1880 to 1881, he served as the secretary of the Black Arkansas Baptist State Convention (ABSC). In 1882, he became the convention’s president, a post he held for thirty-five years. On November 27, 1884, he married Fannie E. Austin of Fackler, Alabama, with whom he had five children.

As president of the ABSC, he oversaw the establishment of a denominational newspaper, the Arkansas Times, later renamed the Baptist Vanguard. He assisted in the establishment of a Black seminary in Little Rock in 1884, which became Arkansas Baptist College in 1886. He also emerged as a leading member of the state Republican Party, serving as a delegate to the National Republican Convention a number of times by the turn of the century. When William McKinley became president in 1897, Morris was suggested for the federal post of Recorder of Deeds for the District of Columbia, but he failed to receive the nomination.

Morris’s career in the church surpassed his political career. In 1892, he received an honorary Doctorate of Divinity from State University of Kentucky in Louisville. By 1894, he had been elected head of the Foreign Missionary Convention, a national body of Black Baptists. In 1895, the convention merged with two other bodies of Black Baptists to become the largest denomination of Black Christians in America—the NBC. Elected its first president, Morris held this post until his death in 1922. In recognition of his work, he received an honorary Doctor of Divinity degree from State University in Louisville, Kentucky in 1892 and, in 1902, an honorary Doctor of Philosophy degree from Agricultural and Mechanical College at Normal, Alabama.

His position as leader of the nation’s Black Baptists earned him recognition among white Christians. In November 1911, he spoke at Arkansas’s white state Baptist convention. He served on the predominantly white executive committees of the General Convention of Baptists of North America, the Baptist World Alliance, and the Congress of English Speaking Peoples of the World. He also served as a vice president of the interracial Federal Council of Churches of Christ.

Morris also helped to develop Black businesses. In 1902, he founded the Helena Negro Business League. He also joined the National Negro Business League and became a close associate of its head, Booker T. Washington of the Tuskegee Institute in Alabama. In 1906, Morris spoke at the Tuskegee Institute’s twenty-fifth anniversary celebration, and in 1908, he hosted a session of the National Negro Business League in Helena.

In 1915, Morris faced a great crisis when Black Baptists loyal to Richard Henry Boyd, head of the Nashville-based National Baptist Publishing Board, broke from the NBC. Despite the intervention of Washington, the rift became permanent.

In 1916, white Republicans led by Augustus Caleb Remmel of Little Rock (Pulaski County) attempted to expel Black leaders from positions in the Arkansas Republican Party. Remmel’s uncle, Harmon Liveright Remmel, ostensibly the head of the party, put forth Morris as a delegate for the national convention; however, the “Lily White” Republicans, joined by Jacob N. Donohoo of Helena, a Black Republican and long-time rival of Morris, prevented him from receiving the nomination.

With America’s entry into World War I, Morris became one of the Committee of One Hundred Speakers named by Governor Charles Brough to tour Arkansas in promotion of the war effort. He also served on the governor’s Commission on Race Relations. However, the end of the war witnessed a worsening of race relations, culminating with the Elaine Massacre in Phillips County in October 1919. After order had been restored, Brough met with Morris and other Black leaders in Little Rock to discuss ways to prevent future violence. When Brough asked Morris his opinion of Arkansas’s segregation laws, he answered, “The Jim Crow laws of the South are a disgrace upon the statute books of the states, for they benefit nobody and do hurt somebody.” His candid answer shocked white leaders; nevertheless, he remained a member of the Commission on Race Relations through 1921.

Race relations continued to be strained in the Arkansas Republican Party. At the state convention in 1920, “Lily White” Republicans attempted to prevent the seating of Black delegates from several counties. A frustrated Morris, whose own seat had not been challenged, led a walkout of Black Republicans, who then held their own convention in which they selected a candidate for governor.

After a lengthy illness, Morris died on September 5, 1922, at the home of his son in Little Rock. He was buried at Dixon Cemetery in Helena.

For additional information:

Carter, Vertie L. Dr. E. C. Morris. Little Rock: VLC Research and Biographical Technical Enterprises, 1999.

Clancy, Sean. “Pioneer Baptist: Exhibition on Influential Rev. E. C. Morris and Centennial Church Details Role of Religion during Jim Crow.” Arkansas Democrat-Gazette, August 22, 2021, pp. 1E, 3E. Online at https://www.arkansasonline.com/news/2021/aug/22/pioneer-baptist/ (accessed July 11, 2023).

Hamilton, G.P. Beacon Lights of the Race. Vol. 2. Memphis: P. H. Clarke and Brother, 1911.

Mather, Frank Lincoln, ed. Who’s Who of the Colored Race: A General Biographical Dictionary of Men and Women of African Descent, Volume One, 1915. Chicago: 1915.

Morris, E.C. Reflections from the Public Services of E. C. Morris, D. D.: Sermons, Addresses and Reminiscences and Important Correspondence, With a Picture Gallery of Eminent Ministers and Scholars. Nashville: National Baptist Publishing Board, 1901.

Memorial Program in Honor of Rev. Elias Camp Morris, D.D. of Helena, Ark. National Baptist Convention, 1923. Special Collections. University of Arkansas Libraries, Fayetteville, Arkansas.

Ryan, Scott C. “‘That These Glorious Results Will at Some Day Be Realized’: An Examination of the Rhetoric of Self-Help, Respectability, and Social Uplift in the Early Works of E. C. Morris.” Baptist History and Heritage 49 (Fall 2014): 7–22.

Tisby, Jemar. The Spirit of Justice: True Stories of Faith, Race, and Resistance. Grand Rapids, MI: Zondervan Academic, 2024.

White, Calvin. “It Should Be More Than Just a Simple Shout: The Life of Elias Camp (‘E. C.’) Morris.” In Race and Ethnicity in Arkansas: New Perspectives, edited by John A. Kirk. Fayetteville: University of Arkansas Press, 2014.

Who Was Who in America. Vol. 1. Chicago: The A.N. Marquis Company, 1942.

Todd E. Lewis

University of Arkansas, Fayetteville

Comments

No comments on this entry yet.