calsfoundation@cals.org

Effect of the California Gold Rush

The California gold rush did not have the positive impact on Arkansas envisioned by its promoters, who hoped for Fort Smith (Sebastian County) to become the hub of westward migration. It did force Arkansas out of its frontier status as people went farther west to California. It also shifted population. John L. Ferguson wrote that, following 1850, Arkansans searching out new opportunity were continuing to move westward; by 1860, some 2,000 Arkansans lived in California, while another 11,000 had emigrated to Texas. The Arkansas Gazette of May 14, 1852, noted that “it is calculated that out of every 100 persons who have gone to California, fifty have been ruined, forty no better than they would have been had they stayed at home, five a little better, and four still better, and one has made a fortune.”

But in 1849, the future beckoned. President James Polk’s State of the Union message was headline news in the Arkansas Gazette on December 22, 1848. Polk confirmed rumors that had circulated for months—that there was indeed gold in California, and plenty of it. Hundreds of Arkansans began to make preparations for the 2,000-mile trek to the goldfields. The failure of the State and Real Estate banks had depreciated currency, businesses and citizens were in debt, and the treasury was empty. Some decided to go for the adventure, while others joined up to escape an unhappy marriage and/or debt. Whatever the reason, the decision to risk the journey was further sealed when the Arkansas State Gazette published a letter from Dr. Walter Colton Alcalde of Monterey, California, on December 29, 1848. He wrote about the fabulous profits to be made as miners recovered what was thought to be an inexhaustible supply of gold, then valued at $18 an ounce. Similar reports were published on a daily basis, adding further encouragement to a prospective gold seeker.

Travelers had a number of choices for their route to California. Some opted for the popular northern Overland Trail, which went by way of Nebraska, Wyoming, and Utah, while others chose one of the branches of the Santa Fe Trail, both of which led out of Independence, Missouri. A number of Washington County emigrants teamed up with a group of Cherokee and blazed the Cherokee Trail, which meandered in a northwest direction out of Fayetteville (Washington County) to join the Santa Fe Trail in the area of McPherson, Kansas, then traveled as far as Pueblo, Colorado, turning north to join the Overland Trail and crossing the Sierra Nevada into California.

Arkansans played an important role in setting a course for California emigrants out of Fort Smith by opening up a southern route to California. With some foresight, creative entrepreneurs began meeting to promote the reopening of a trace leading from Fort Smith across Indian Territory to Santa Fe, which Josiah Gregg had blazed along the Canadian River in the spring of 1839 on one of his early trading excursions.

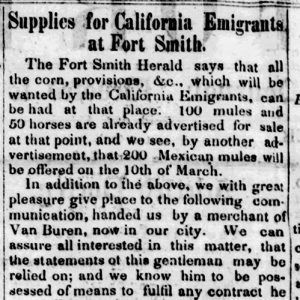

The Fort Smith Herald began an advertising campaign resulting from hundreds of letters received from prospective gold seekers all over the eastern seaboard. It responded with a circular bearing the caption, “HO FOR CALIFORNIA,” offering information on the proposed route, which they called the Fort Smith-Santa Fe Trail. Included was advice on food supplies, wagons and teams, clothing, and weapons.

As thousands began to gather in Fort Smith and neighboring Van Buren (Crawford County), they learned that they would not be traveling unprotected. The editor of the Fort Smith Herald and several colleagues asked one of Arkansas’s U.S. senators, Solon Borland, to petition the secretary of war, William L. Marcy, for a 100-man military escort to protect the “Forty-niners,” as they came to be known, and to construct a national road between Fort Smith and Santa Fe. An army appropriation bill was approved on March 3, 1849, for a sum of $50,000, which was to cover the expense of a survey by the topographical engineers and, at the same time, provide escort for the emigrants. Captain Randolph B. Marcy of the Fifth United States Infantry was selected to escort the emigrants, and Lieutenant J. H. Simpson, topographical engineer, was appointed to survey and construct a wagon road from Fort Smith to Santa Fe. The troops started out on April 4, 1849.

Citizens wasted no time in organizing. For example, some forty citizens of Little Rock (Pulaski County) formed a company in early January (the Little Rock and California Association), published its articles of association, and recommended a departure date from Fort Smith on March 25, 1849. The Fort Smith Company had begun forming as early as December 1848. Others followed suit. More than 100 people from Clarksville (Johnson County) organized under Redmond Rogers, and those from Fayetteville organized under Captain Lewis Evans. From Van Buren came a group with wagons and another with pack mules. Cherokee and Arkansans formed a company under J. N. A. Carter at Fort Gibson in Indian Territory. In the beginning, this was mainly an emigration of men, both married and single, although there were a few families in the Clarksville Company. Many men left behind their wives to run plantations and businesses and care for children for at least two years, while they labored in the mines.

As Arkansans began gathering at Fort Smith, hundreds of individuals from neighboring states joined the crowd. By April 28, a correspondent from the Baltimore Sun guessed that some 900 wagons with 2,000 emigrants, along with thousands of mules, horses, and oxen, had left with the troops on April 4. There was no doubt that the emigration helped the Fort Smith and Arkansas economy considerably, and in spite of the fact that thousands of citizens had left for the gold fields, the 1850 population of Arkansas was 209,000, an increase of 112,000 citizens since 1840.

Emigrants were left to choose from a number of travel options out of Santa Fe. Many companies had divided into smaller units, while others reorganized. Some sold their wagons in exchange for pack mules and opted for a course down the Rio Grande to modern Truth and Consequences, New Mexico, where they turned west to travel a rugged terrain along the course of the Gila River all the way to the Yuma Crossing on the Colorado River. Most Arkansas emigrants, however, opted to follow a trail opened by Philip St. George Cooke in 1846 as he led the Mormon Battalion, another contingent of the Army of the West, to California. In this case, they left the Rio Grande near modern Garfield, New Mexico, traveled southwest over the Animas Mountains into the New Mexico Bootheel, then through the rugged Guadalupe Pass on the international border with Mexico. At this point, the emigrants found themselves in Sonora, Mexico, near the ruins of San Bernardino Rancho, where they hunted wild bulls. They followed the Santa Cruz River to the Mission San Xavier del Bac and the presidio of Tucson, Arizona, before trudging across a searing Sonoran desert to the villages of the friendly Pima Indians on the Gila River. Continuing west along the Gila River, these travelers ultimately connected with the Colorado River at Yuma, Arizona, where Yuma Indians helped swim their animals and wagons across.

Robert Brownlee of Little Rock was one of many Arkansans who left a journal of his experiences, and there are many whose correspondence of the time survives. Arkansas newspapers frequently published the written works of those traveling to California during the gold rush. Excerpts from the journal of F. J. Thibault were published in the Arkansas State Gazette & Democrat on January 31, May 9, and July 11, 1851; letters by Alden M. Woodruff, son of Arkansas Gazette founder William E. Woodruff, were published in the Arkansas State Democrat on August 7 and December 21, 1849, and January 25, 1850, and in the Arkansas State Gazette & Democrat on April 19 and 26 and October 11, 1850.

Following the gold rush, Arkansans’ travel between Fort Smith and Santa Fe began to spark national interest, and in 1853, Lieutenant Amiel Weeks Whipple began his survey at Fort Smith for a railroad from the Mississippi River to the Pacific Ocean, basically following the emigrant road along the Canadian River. That railroad route never materialized. Next came the Butterfield Overland Mail Company in 1858, terminating in Fort Smith. Again, with variations in the route, the Fort Smith-Santa Fe Trail ultimately became Interstate 40 across Oklahoma, New Mexico, and northern Arizona into California. The southern segment of the trail evolved into Interstate 10 between Las Cruces, New Mexico, and Tucson.

There is no solid estimate as to the number of Arkansans who returned home after their sojourn in the mines. Some returned to Arkansas to retrieve their families and moved to California for a year or two before returning permanently. A number died and were buried in graves near the trail. Some returned to Arkansas to lead another contingent to the mines. Others never came back. A majority likely became heartily sick of the whole experience and returned home without having achieved much in the way of riches.

James Calvin (Cal) Jarnagin was one of the lucky gold seekers. He traveled to California with the Clarksville Company from Johnson County and ended up in Sonora, in the Southern Mining District. Here, he lived in a rough log cabin with several fellow miners. One day in 1850 found him “digging by myself in the claim when suddenly my pick broke away part of a bank of earth and there in front of me a piece of gold lay exposed…shaped like a common corn-doger, it was very nearly pure gold!” As it turns out, the nugget weighed in at 23 pounds, 11 3/4 ounces. Ultimately, Jarnagin sold it for $3,000. Following a number of years’ residence in California, he returned to Arkansas and married Matilda Caroline Pittman.

James McVicar traveled with the Little Rock Company and ultimately settled in Quartzburg, in the Southern Mining District, where he became a partner in the enormously rich Washington Quartz Mine in 1850. Sam Ward wrote that the proprietors offered him half of the mine for $14,000. In addition, McVicar opened a “trading establishment,” where he had an “eating house, bakery, and rummery” near Indian Bar on the Tuolumne River. McVicar ultimately returned to Little Rock, where he married Amanda Miller in 1856.

Some found gold in other ways. Robert Brownlee of Little Rock opened a tent store in the mining town of Agua Fria. He and his partner, John W. Clark, made a good deal of money selling mining supplies, canned goods, liquor, clothing, and even Panama hats to the miners and members of the Mariposa Battalion. Brownlee returned to Little Rock briefly to sell the house he built (now preserved at the Historic Arkansas Museum) and moved permanently to his ranch in Napa County, California.

Whatever the case, the men and women who participated in the greatest mass migration in American history would never be the same. Although some may have been embittered, others were strengthened by the experience. Many returned with a greater understanding of their fellow man and the indigenous peoples and cultures they met along the way. They encountered and overcame enormous physical challenges on the deserts and in the mountains. And they saw an immense, beautiful country, largely uninhabited except for its Native Americans. Their collected reminiscences form a unique perspective of adventure and the origin of southern trails in an era that continues to excite the imagination.

For additional information:

Akins, Jerry. “Fort Smith and the Gold Rush: The Impact of the 1849 Gold Seekers on the City.” Journal of the Fort Smith Historical Society 34 (September 2010): 16–19.

Alfred D. King Journal, 1849. Special Collections. University of Arkansas Libraries, Fayetteville, Arkansas.

“Arkansas’ Golden Army of ’49.” Special issue, Arkansas Historical Quarterly 6 (Spring 1947).

Bier, James A. Western Emigrant Trails, 1830–1870: Major Trails, Cutoffs, and Alternates. 2d ed. Independence, MO: The Oregon-California Trails Association, 1993.

Brownlee, Robert. An American Odyssey: The Autobiography of a 19th-Century Scotsman, Robert Brownlee, at the Request of His Children. Napa County, California, October 1892. Edited by Patricia A. Etter. Fayetteville: University of Arkansas Press, 1986.

Collins, Carvell. Sam Ward in the Gold Rush. Palo Alto, CA: Stanford University Press, 1949.

Conway, Mary. “Little Rock Girl Rides Horseback to California in Gold Rush Days.” Pulaski County Historical Review 12 (March 1964): 6–9.

Emory, William Hemsley. Notes of a Military Reconnaissance from Fort Leavenworth, in Missouri to San Diego, in California, Including Part of the Arkansas, del Norte and Gila Rivers. Thirtieth Congress, First Session, Ex. Doc. No. 41, 1848.

Etter, Patricia A. To California on the Southern Route, 1849: A History and Bibliography. Spokane, WA: The Arthur H. Clark Company, 1998.

Ferguson, John L., and J. H. Atkinson. Historic Arkansas. Little Rock: Arkansas State Archives, 1966.

Foreman, Grant. Marcy and the Gold Seekers: With the Journal of Capt. R. B. Marcy With an Account of the Gold Rush over the Southern Route. Norman: University of Oklahoma Press, 1968.

Gregg, Josiah. Commerce of the Prairies. New York: H. G. Langley, 1844.

Griffith, Nancy Snell. “Batesville and the 1849 California Gold Rush.” Independence County Chronicle 40 (October 1998–January 1999): 39–57.

McArthur, Priscilla. Arkansas in the Gold Rush. Little Rock: August House, 1986.

Self, Jean. “Jarnagin’s Gold: Big Nuggets Were Found in Old Sonora Camp.” The Quarterly of the Tuolumne County Historical Society 7 (October–December 1967): 221–223.

Stith, Matthew M. “‘How! For California!’: Fort Smith, Van Buren, and the Rush to the Gold Fields.” Ozark Historical Review 35 (2006): 50–61.

Patricia A. Etter

Emeritus College, Arizona State University

Comments

No comments on this entry yet.