calsfoundation@cals.org

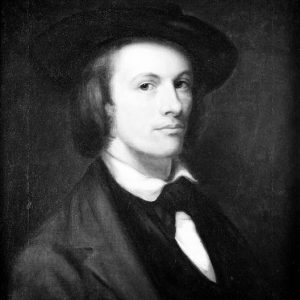

Edward Payson Washbourne (1831–1860)

Of the many artists who lived and worked in antebellum Arkansas, none gained greater acclaim than Edward Payson Washbourne, creator of one of the Western frontier’s most memorable and humorous genre scenes, The Arkansas Traveler. Noted not only for his allegorical works, Washbourne was also widely sought for portraiture. Examples of his work can be seen in the collections of the Historic Arkansas Museum and the Arkansas State Archives in Little Rock (Pulaski County).

Edward Washbourne was born on November 16, 1831, at Dwight Mission, then located in Indian Territory (present-day Oklahoma); the 1850 census lists him as being born in Arkansas, but the western border of Arkansas was in flux at the time of his birth. He was the son of famed Presbyterian missionary Cephas Washburn, who moved to Arkansas in 1820 to establish a mission among the westward-migrating Cherokee, and Abigail Woodward Washburn; he had four siblings. By 1831, the Washburns, along with thousands of Cherokee, were removed by treaty to a new home in what is now northeastern Oklahoma. There, young Washbourne first began to make rudimentary sketches and dream of his future as an artist. But it was in Fort Smith (Sebastian County)—where the Reverend Washburn moved his family in 1851—that the nineteen-year-old Washbourne received his first formal art training and began trying his hand at selling his services as a portraitist.

According to family oral history, the sons of Cephas Washburn—Josiah Woodward, Henry A., and Edward (or Eddy, as he was known)—began using what they believed to be an “Old” English and more correct spelling of their last name to differentiate themselves from their Northern cousins. This difference had much to do with their support for the pro-slavery South as opposed to their abolitionist kinfolk in Vermont and Connecticut.

No doubt aware he needed further training to pursue his artistic goals, young Washbourne struck out for New York City early in 1853. Contemporary accounts state that he studied for eighteen months with famed portraitist Charles Loring Elliott, who was considered by many to be the finest portrait painter in America. According to family tradition, Elliott may have gotten one or more of young Washbourne’s works exhibited at the National Academy of Design. Washbourne stated that he planned on traveling abroad to Europe to continue his studies; however, a lack of funds may have put his travel plans on hold, and, by 1855, he had returned to Arkansas with brush and palette in hand. Soon, Fayetteville (Washington County), Little Rock, Fort Smith, and Washington (Hempstead County) all became temporary home and studio for the artist as he traveled around the state painting the portraits of the great and near-great. In a July 6, 1856, letter to his brother, James Woodward Washbourne, the young artist served up a marvelous account of the nomadic life of a typical American portrait painter: “I am in Sevier Co. where I came to rusticate a little & paint a little. I am staying at Col. Ben Hawkins…painting 6 portraits for Hawkins, 3 boys on one canvas. Col. Hawkins is a perfect Arkansas Gentleman.”

In this same letter, Washbourne mentioned for the first time that he had completed what would become his artistic opus, The Arkansas Traveler. The painting depicts an event that was already well known as play, folktale, and fiddle tune: a mounted traveler has stopped at the dilapidated log cabin of a backwoods squatter, whom he finds sitting on a barrel with his fiddle playing an incomplete version of a familiar tune known far and wide as “The Arkansas Traveler”; a dialogue ensues, with the traveler agreeing to finish the second half, or “turn,” of the tune in exchange for lodging for the night. In his letter, Washbourne further confided that he hoped to go to New York City to see about having prints made. In the end, The Arkansas Traveler was lithographed in Boston, Massachusetts, by the well-known firm of J. H. Bufford, which, by the fall of 1859, made the first-known lithographs of the painting available to the public. An initial printing of 1,500 was commissioned, with approximately half of the prints being sent directly to Washbourne, while the rest were consigned to a variety of dealers around the country or kept in Boston, subject to order.

The popularity of The Arkansas Traveler print was immediate and overwhelming. Washbourne’s plans to study abroad now seemed within reach. He had also confided to family and friends that he planned, at some point, to open a grand gallery of Southern art in Memphis, Tennessee. However, in March 1860, while painting in Little Rock, the young artist suddenly became ill. On March 26, 1860, he died. Washbourne had unexpectedly been present at his father’s death on March 17, 1860. Both father and son are interred at Little Rock’s historic Mount Holly Cemetery. The Pulaski County Historical Society installed a marker on Washbourne’s grave (with his name spelled Washburn) in 1958; the dedication ceremony featured a talk by historian John Ferguson.

By 1870, the well-known firm of Currier and Ives created its own version of The Arkansas Traveler. Soon after, they paired it with another, less well-known version of the Traveler tale, again painted by Washbourne, titled, The Turn of the Tune, which depicts the traveler winning over the squatter and his rustic brood by taking up the fiddle and playing the “turn” of the squatter’s tune. Washbourne had been working on completing the original painting at the time of his death.

For additional information:

Bennett, Swannee. The Likeness Trade: Portrait Painting in Arkansas, 1780–1900. Exhibit catalog. Little Rock: Arkansas Territorial Restoration, 1996.

Bennett, Swannee, and William B. Worthen. Arkansas Made: A Survey of the Decorative, Mechanical and Fine Arts, 1819–1870. Vol. 2. Fayetteville: University of Arkansas Press, 1991.

Brown, Sarah. “The Arkansas Traveller: Southwest Humor on Canvas.” Arkansas Historical Quarterly 46 (Winter 1987): 348–375.

Hancox, Louise M. “Picturing a Nation Divided: Art, American Identity, and the Crisis over Slavery.” PhD diss., University of Arkansas, 2018.

Masterson, James R. Arkansas Folklore: The Arkansas Traveler, Davy Crockett and Other Legends. Little Rock: Rose Publishing Co., 1974. (Facsimile reprint of Tall Tales of Arkansas. Boston: Chapman and Grimes, 1942.)

Park, Hugh. Reminiscences of the Indians by Cephas Washburn. Van Buren, AR: Press-Argus, 1955.

Swannee Bennett

Historic Arkansas Museum

Comments

No comments on this entry yet.