calsfoundation@cals.org

Edward Coy (Lynching of)

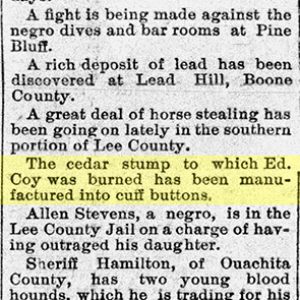

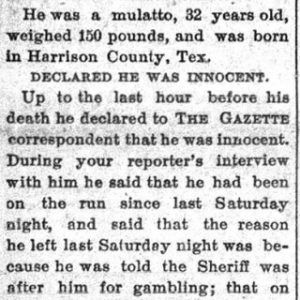

On February 20, 1892, Edward Coy, a thirty-two-year-old African-American man, was burned at the stake in Texarkana (Miller County) before a crowd of approximately 1,000 people. Ida B. Wells, a journalist and prominent anti-lynching crusader, described Coy’s murder as one of the most shocking and repulsive in the history of lynching. Coy, described in press accounts as “mulatto,” was charged with a crime “from which the laws provide adequate punishment. Ed Coy was charged with assaulting Mrs. Henry [Julia] Jewell, a white woman. A mob pronounced him guilty, strapped him to a tree, chipped the flesh from his body, poured coal oil over him, and the woman in the case set fire to him.”

According to the New York Times, Jewell was attacked and raped by a “negro” who visited her house to sell hogs to her husband. The man attacked her when she told him her husband had gone to town. Following the attack, her husband returned and gave the alarm. Men scoured the country around Texarkana in all directions. Two suspects were apprehended, but Julia Jewell pronounced them innocent.

During the search, it was learned that the suspect being sought was named Ed Coy. It was believed that Coy had fled “northwards towards Little River County, Arkansas.” Another suspect was arrested and brought before Jewell, who “pronounced him not the man, although the hat and clothes he wore looked exactly like those of her assailant.” The prisoner explained the clothing by saying that “he and Coy had been together on Sunday and Monday and at the latter’s request they had swapped clothes. Coy said that they were after him for some minor offense.”

The next morning, a farmer, W. B. Scott, who lived just five miles outside of Texarkana, found Ed Coy and held him until a posse, headed by Noah Sanderson, arrived and took possession of Coy. The posse, consisting of about fifty mounted guards, “attended the prisoner to town, arriving…about 9 o’clock.” Jewell identified Coy as the man who attacked her.

By 2:00 p.m., a decision had been made to hang Coy. A crowd of 1,000 marched Coy to the Iron Mountain roundhouse. A large stake was found here, “and in a twinkling he was securely bound to it. One from the mob advanced with a can of coal oil, and the crowd then knew what fate was in store for the negro.” The crowd cried, “BURN HIM! BURN HIM!” Julia Jewell, the alleged rape victim, was given a torch. She looked at Coy, looked at the torch, and seemed to falter until, as one, the entire crowd yelled, “Burn him!” She applied the torch, and the crowd watched Coy burn alive.

It was reported in a “Special” to the Republic newspaper of Texarkana that “Mrs. Henry Jewell was a respectable farmer’s wife, with a five-months-old child at the breast.” However, an investigation by Judge Albion Winegar Tourgée, a pioneer civil rights activist, published in the Chicago Inter Ocean on October 1, 1892, stated, “The woman who was paraded as a victim of violence was of bad character; her husband was a drunkard and a gambler. She was publicly reported and generally known to have been criminally intimate with Coy for more than a year previous. She was compelled by threats, if not by violence, to make the charge against the victim.” (It is unclear if Tourgée traveled to Arkansas for his investigation.) Indeed, Coy contended, right up until his death, that he and Jewell were lovers by mutual desire and consent. As she applied the torch to his oil-soaked body, he turned to her and asked how she could burn him after they had “been sweethearting” so long.

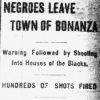

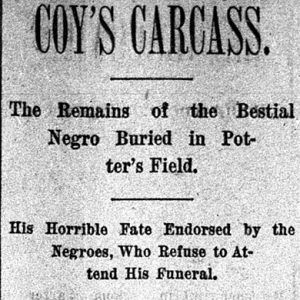

Coy’s murder attracted national attention, and the New York Times supported Wells’s accusation that sheriffs and police simply looked on when it wrote, “Marshall Crenshaw, accompanied by a small posse, took the negro in charge.” The Times continued with, “a crowd of 1,000 people secured Coy from his captors as they were bringing him to the city.” The Arkansas Gazette added a sad commentary on the South when it wrote, “People witnessed his burning, thus endorsing it with their presence.” The murder of Coy typifies a trend in lynching toward greater public spectacle, the acts being carried out by people who felt no need to hide their identities. By contrast, lynching in the early decades following the Civil War was often done in secret, usually at night.

The lynching of Edward Coy remained a part of public consciousness throughout the United States for many years. On June 4, 1899, the Reverend D. A. Graham delivered a sermon at Bethel AME Church in Indianapolis, Indiana, on the subject of lynching. In part, Graham said, “The greatest affliction we have to suffer is the lack of trial by jury when accused of crime. Lynching of Negroes is growing to be a Southern pastime.” When speaking of Coy, Graham said, “The relatives and husband of the woman who made the charge were fully cognizant of the fact that she was equally guilty with Coy. They compelled her to make the charge and then to set fire to her paramour.”

For additional information:

“At the Stake.” Arkansas Gazette, February 21, 1892, p. 1.

Graham, Rev. D. A. “Some Facts about Southern Lynchings.” Indianapolis Recorder, June 10, 1899. Online at http://www.blackpast.org/?q=1899-reverend-d-graham-some-facts-about-southern-lynchings (accessed February 7, 2024).

“A Negro Burned Alive.” New York Times. February 21, 1892, p. 6. Online at https://www.nytimes.com/1892/02/21/archives/a-negro-burned-alive-roasted-alive-in-the-presence-of-a-thousand.html?searchResultPosition=1 (accessed February 7, 2024).

Wells, Ida. B. “Lynch Law in All Its Phases.” Our Day, May 1893, pp. 333–337.

Larry LeMasters

LeMasters’ Antique News Service

Comments

No comments on this entry yet.