calsfoundation@cals.org

Eagle-Booe Feud

On April 25, 1898, three men were shot to death in Lonoke (Lonoke County). These killings—and the conflicts that took place before and after—have come to be called the Eagle-Booe Feud. The prominent Eagle family of Lonoke County, including the brother of a former Arkansas governor, was roped into the feud and ended up being defended in court by a distant relation who would became governor himself, and later a U.S. senator.

Approximately a week before the killings, on or about April 19, 1898, an unknown assailant shot Charles (Charley) Booe (wrongly spelled sometimes as Booie) outside of his law office in England (Lonoke County). Charley Booe, for reasons unknown, accused Robert (Bob) Eagle of shooting him. Booe’s father, William K. Booe, and brother, William (Will) Booe, believing that Charley Booe’s accusation against Eagle was true, swore to exterminate the Eagle family.

William K. Booe, armed with a gun, immediately went to the storehouse in England owned by Bob Eagle. Booe stayed at the storehouse for a considerable time, declaring he was there to kill Bob Eagle. Eagle left his store by a back door and escaped to Lonoke, where he reported Booe’s assassination plans to friends and family.

Before bloodshed occurred, friends of both families tried to restore harmony between the two families. The Eagles seemed willing to make peace to avoid continued violence, but the Booe family members insisted that only blood would satisfy them.

The Eagle clan, having been told that William K. Booe and Charley Booe would join Will Booe in Lonoke on April 25, took up arms. They were waiting in ambush on the south side of the Lonoke train depot when the Booes arrived. After conferring at the depot for a moment, the three Booes, all heavily armed, proceeded down Center Street, south of the depot. As the three men neared the corner by Ruble’s Store, the Eagles fired at them. Within minutes, all three Booes lay dead.

The Booe clan had a long history of violence and was known around Lonoke to be dangerous. William K. Booe, who was a saloonkeeper in his younger days, had once shot and seriously wounded two men (Print Lowe and Jack Carroll) over trivial debts. However, at the time of his death, Booe was a member of the Methodist Church and was regarded as a good citizen and leading merchant of Lonoke. His son Will Booe possessed a violent and dangerous temper, once shooting a customer in his father’s store named Conley twice in the back over the matter of a small debt.

As a young man, Charley Booe had killed a thirteen-year-old boy, escaping to Texas to avoid prosecution. Ironically, it was William H. Eagle—father of Joe P. Eagle and R. E. L. Eagle—who helped Charley Booe gain an acquittal for this crime. Following his acquittal, Charley Booe practiced law in England, as well as terror in Lonoke, threatening to kill a number of Lonoke citizens and terrorizing the entire town with his reckless behavior.

After the shooting near Ruble’s Store, the New York Times declared, “Booies of Arkansas taken by surprise by the Eagles and shot down in cold blood.” Joe P. Eagle, Joe E. Eagle, Bob Eagle, Dave Eagle, Miles Eagle, and brother-in-law Robert S. Daughtry were arrested for killing the three Booes and released on $1,000 bonds.

The Eagle family was well-known and respected in Lonoke County, where it dominated local politics for years. William H. Eagle, one of Lonoke County’s wealthiest land owners, was the patriarch of the Eagle family and brother of former Arkansas governor James P. Eagle. The grand jury refused to indict the Eagle clan on murder charges, returning indictments for second-degree murder only. Amid sweltering heat, the local judge, afraid of offending the Eagle or the Booe clans and being killed himself, disqualified himself from the case, leaving the bench open for an outsider.

Joe T. Robinson, distant kin to the Eagle family, represented the Eagle faction, giving an effective closing argument to the jury and painting Charley Booe as an outlaw. Robinson added that the Booes had threatened the “extinction” of the Eagle family, so the Eagles were acting in self-defense at the time of the shootings. All six of the Eagle men were acquitted.

Citizens of Lonoke expected some of the extended Booe family to seek a blood vengeance against the Eagle clan, but this never happened. Times were changing in Arkansas, and the heyday of the blood feud was quickly drawing to a close. The murders of William K., Charley, and Will Booe effectively ended the Eagle-Booe Feud.

For additional information:

“Eagles Are Not Guilty.” Arkansas Gazette, August 28, 1898, p. 1.

“Eagles Second Trial.” Arkansas Gazette, September 2, 1898, p. 2.

“Killing of the Booes—Done by the Eagles.” Arkansas Democrat, April 26, 1898, p. 2.

“Shot to Kill—Eagles Killed Booes.” Arkansas Gazette, April 26, 1898, p. 2.

“Three Killed in a Feud.” New York Times, April 26, 1898, p. 5.

Larry LeMasters

LeMasters’ Antique News Service

Post-Reconstruction through the Gilded Age, 1875 through 1900

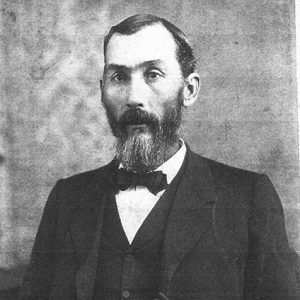

Post-Reconstruction through the Gilded Age, 1875 through 1900 William H. Eagle

William H. Eagle

In 1898, my grandfather, Thomas Abbott Hestir, had a hardware store in Lonoke. He was married (to Mable Ann Hard Hestir) and they had a three-month-old infant son (Myron Louis Hestir) when the Eagle and Booe family feud broke out in violence on the Main Street in town. Even though there were several people who were shot and killed, apparently no arrests took place immediately after the event. When people came in his store he expressed his disbelief and shock that with murders occurring on the Main Street in town that nobody had been arrested. Not long after, some men (apparently from the Eagle family) came into his store with guns and said that if he didn’t keep quiet that they would kill him too. He felt like he couldn’t raise his family and live in a town where murderers went free, so he went home and put his wife and infant son on the next train out of town to Iowa, where her parents were living. He stayed in Lonoke for some time in order to sell the store and then joined his family in Iowa. In recounting this story some years later, someone asked if he hadn’t been afraid to go home at night for fear that someone might be in the house. He said he wasn’t afraid because after stepping through the front door he would pause for a few moments. He said he was sure he would sense if someone was there or if it was safe to go in.