calsfoundation@cals.org

Dick Allen (1942–2020)

aka: Richard Anthony Allen

Richard Anthony (Dick) Allen—or Richie Allen, as the media called him early in his career—was the first African American to play for the minor league baseball team based in Little Rock (Pulaski County). That same year, 1963, official baseball records first recognized the team’s name change from the Little Rock Travelers to the Arkansas Travelers. After one season in Little Rock, Allen had a memorable, though controversial, career in the major leagues.

Dick Allen was born on March 8, 1942, in Wampum, Pennsylvania, the second youngest of nine children born to Era Allen and Coy Allen, a traveling truck driver and self-employed sanitation worker who later divorced her. Era Allen raised Dick Allen primarily on her own. Allen’s family was well known in Wampum because of the athletic talents Allen and his brothers had demonstrated throughout their school years. Though they were one of the few black families in Wampum, a town of 1,000 about thirty miles from Pittsburgh, the Allens experienced no overt discrimination.

The Philadelphia Phillies signed Allen in 1960 for $70,000, the highest signing bonus ever paid a black player at the time. The organization and the Philadelphia media called him “Richie,” perhaps in an attempt to link him in fans’ minds with Philadelphia’s star player, Richie Ashburn. Allen had always been called Dick and disliked the “Richie” nickname; the name controversy later was one of the disputes between him and sportswriters.

The teenager progressed rapidly through the Phillies’ minor league system. By age twenty, he was ready for AAA baseball, the final minor league stop before the majors. Philadelphia had a new AAA affiliate in 1963, as baseball returned to Little Rock after a year’s absence following the collapse of the Southern Association. The Arkansas Travelers were a new member of the International League and now were classified AAA.

Little Rock held an infamous place in history because of the 1957 desegregation of Little Rock Central High School. Those events concerned Allen, who had never been to the South. He asked Phillies officials not to send him to Arkansas to play, to no avail. In later years, Allen faulted the organization for the little support it provided him in his year in Little Rock.

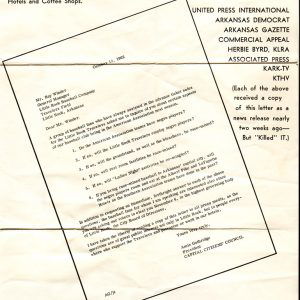

Little Rock sportswriters made passing reference during spring training to Allen’s race as they wrote about the upcoming season, but the fact that Allen would be the first black Traveler was never reported. Jim Bailey, an Arkansas Gazette baseball writer, confirmed years later that Gazette editors told reporters not to mention that Allen would be the first black Traveler. The newspaper had suffered economically for its stand in support of Central High’s desegregation and adopted a different approach to the integration of the Travelers. “The editors decided we’d be better off not getting things all stirred up again,” Bailey said. The Arkansas Democrat adopted a similar approach. In pre-season articles, his race was mentioned occasionally but not his being the Travelers’ first black player.

Opening night in Little Rock still featured the tension that the newspapers had hoped to avoid. Marchers, led by White Citizens’ Council leader Amis Guthridge, picketed the ballpark carrying signs that read, “Don’t Negro-ize baseball” and “Nigger go home.” Governor Orval Faubus, a nationally known opponent of school integration, threw the game’s ceremonial first pitch before a standing-room-only crowd of nearly 7,000, including about 200 black fans. As the national anthem played before the game, out in left field, the Travelers’ first black player repeated the twenty-third Psalm to himself.

The first pitch resulted in a routine fly ball hit to left. Allen later recalled: “I froze….The ball flew over my head. I missed the ball because I was scared. I don’t mind saying it.” He made amends for his fielding error later in the game. He hit two doubles, the second of which led to the Travelers’ taking the lead and winning the game.

Allen was the last player to leave the park that night. He found a note on his car’s windshield that read, “Don’t come back again, nigger.”

Allen led a life separate from his teammates during his season in Little Rock. He lived with a black family in a black section of town (Little Rock’s neighborhoods were segregated). He ate in restaurants only when accompanied by white teammates. He received threatening notes and letters throughout the season.

Even during the games, Allen heard racial slurs from the grandstand as he returned to the dugout between innings. Despite this, he led the team in hitting at .290 and the league in home runs (thirty-three), runs batted in (ninety-seven), and triples (twelve). His thirty-three homers by a right-handed hitter remained a Traveler record for nearly forty years. Fans voted Allen the team’s most valuable player at season’s end.

Allen was called up to Philadelphia in September 1963 to begin a fifteen-year career in the major leagues. He frequently was at odds with sports writers, fans, and team management over his treatment by those groups. Reporters and baseball fans in Philadelphia became highly critical of Allen and welcomed, as did Allen, his eventual trade to St. Louis in 1969, the first of several trades that would be made for the talented player.

Some writers, in reviewing Allen’s career in later years, contend that Allen’s experiences integrating baseball in Little Rock contributed to these later disagreements. Allen might well have agreed with that assessment. In his biography, Crash, Allen wrote that in Little Rock he learned that two sets of rules existed: one set for the white players and one set for Allen. In the future, Allen wrote, if there were going to be two sets of rules, he would see to it that the rules governing himself were of his own choosing.

Allen was the National League’s Rookie of the Year in 1964 and the American League’s Most Valuable Player in 1972, when he played for the Chicago White Sox. Allen was selected for the All-Star game seven times before retiring in 1977, having played for six different teams in his fifteen-year major league career.

Allen had married prior to beginning his baseball career. He and his wife, Barbara, had three children and later divorced.

Allen lived in Los Angeles, California. In December 2014, Allen missed being elected to the National Baseball Hall of Fame by only one vote. He died on December 7, 2020. In 2024, he was finally elected to the National Baseball Hall of Fame.

For additional information:

Allen, Dick, and Tim Whitaker. Crash: The Life and Times of Dick Allen. New York: Ticknor & Fields, 1989.

Campbell, Matt. “Dick Allen, First Black Player for the Arkansas Travelers, Elected to the National Baseball Hall of Fame.” Arkansas Times, December 9, 2024. https://arktimes.com/arkansas-blog/2024/12/09/dick-allen-first-black-player-for-the-arkansas-travelers-elected-to-the-national-baseball-hall-of-fame (accessed December 16, 2024).

Jacobson, Matthew Frye. “‘Richie’ Allen, Whitey’s Ways and Me: A Political Education.” In In the Game: Race, Identity, and Sports in the Twentieth Century, edited by Amy Bass. New York: Palgrave, 2005.

Kashatus, William C. September Swoon: Richie Allen, the ’64 Phillies, and Racial Integration. University Park: Pennsylvania State University, 2004.

Kepner, Tyler. “Dick Allen, Dave Parker Elected to Baseball Hall of Fame by Era Committee.” The Athletic, New York Times, December 8, 2024. https://www.nytimes.com/athletic/5979358/2024/12/08/dick-allen-dave-parker-baseball-hall-of-fame/ (accessed December 16, 2024).

March, Lochlahn. “Revisiting a ‘Graveyard’ on the Way to Cooperstown.” Philadelphia Inquirer, July 22, 2025. Online at https://www.inquirer.com/phillies/a/dick-allen-hall-of-fame-induction-class-2025-arkansas-travelers-documentary-20250722.html (accessed July 24, 2025).

Nathanson, Mitchell. God Almighty Hisself: The Life and Legacy of Dick Allen. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 2016.

Razer, Bob. “The Black Traveler: Dick Allen and Little Rock Baseball, 1963.” Pulaski County Historical Review 61 (Spring 2013): 2–10.

Rhoden, William C. “Weighing the Complexity of a Hall Candidate, and His Times.” New York Times, December 7, 2014, http://www.nytimes.com/2014/12/07/sports/baseball/weighing-the-complexity-of-a-hall-candidate-and-his-times.html (accessed July 11, 2023).

Bob Razer

Bill Clinton State Government Project

Central Arkansas Library System

The Black family that Richard Anthony Allen lived with for one year with the Arkansas Travelers in 1963 before being called up by the Philadelphia Phillies were the Hugheses: Charlie and Hattie, at 2121 S. Chester Street in Little Rock. The Hugheses were business owners on 9th Street providing hair services–barber and cosmetology, respectively. Charlie was the first Black Arkansas barber inspector.

Richie Allen was also the subject of a song by singer and songwriter Chuck Brodsky called “Letters In the Dirt.” I’ll allow Chuck to explain: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=qIrZSc54mWE

Allen was the lone African American on the team that year, and the only black position player. But future Hall of Fame member Ferguson Jenkins (a Canadian) and Marcelino Lopez (from Cuba) were pitchers on the 1963 squad.

I was thirteen years old in 1963 and a Travelers fan. In a previous season, I used to sit in section W, Row 1, Seat 10, the closest seat to the bullpen. I actually talked to the pitchers and got a ball from Bo Belinsky, although I couldn’t buy him a beer even with his ID. I do not remember the opening day pickets on April 16th or all the other racist stuff, although I was not a liberal at the time. I was 13. But I do remember the game. It was also the day that two events that would change life forever happened in Little Rock, one personal and one global. There is much written about the night that baseball was integrated in Little Rock. However, what ties me to that day is personal. It was two days after Larry Storthz’s birthday, and I attended that game with Steve Tuck and Larry. We were driven to the game by my dad. Later, I was called over the PA. I was then told my dad was real sick. I was picked up by neighbors and told my father had died. Sam Levine died at the same time Dick Allen was making his debut, and my world was never the same. I followed his career from then on.