calsfoundation@cals.org

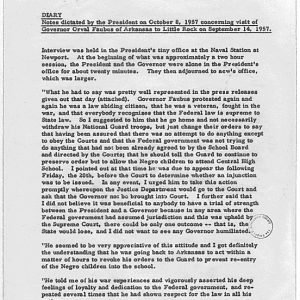

Desegregation of Central High School

aka: Crisis at Central High

aka: Little Rock Desegregation Crisis

In its 1954 Brown v. Board of Education of Topeka, Kansas decision, the U.S. Supreme Court ruled that racial segregation in public education was a violation of the Fourteenth Amendment to the Constitution. As school districts across the South sought various ways to respond to the court’s ruling, Little Rock (Pulaski County) Central High School became a national and international symbol of resistance to desegregation.

On May 22, 1954, the Little Rock School Board issued a statement saying that it would comply with the Court’s decision, once the court outlined the method and time frame for implementation. Meanwhile, the board directed Superintendent Virgil Blossom to formulate a plan for desegregation. In May 1955, the school board adopted the Phase Program Plan of gradual desegregation that became known as the Blossom Plan, after its author.

The plan was originally conceived to begin at the elementary school level. However, as parents of elementary school students became some of the most outspoken patrons against integration, district officials decided to begin token desegregation in the fall of 1957 at Central High School, to expand to the junior high level by 1960 and, tentatively, to the elementary level by 1963. The plan also included a transfer provision that would allow students to transfer from a school where their race was in the minority. This assured that students at Horace Mann High School would remain predominantly African American.

Later that May, the U.S. Supreme Court issued its Brown II decision, directing districts to proceed with desegregation with “all deliberate speed.” The Court returned the case to federal district courts for implementation.

In February 1956, the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP) filed suit against the Little Rock School District on behalf of thirty-three African American students who had attempted to register in all-white schools. In the suit, Aaron v. Cooper, the U.S. Court of Appeals for the Eighth Circuit upheld the school district’s position that the Blossom Plan complied with the Supreme Court’s instructions. The federal court retained jurisdiction in the case, making compliance with the plan mandatory.

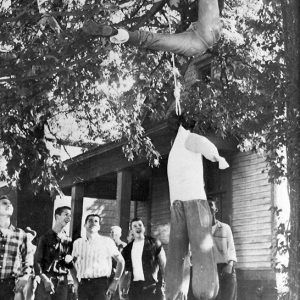

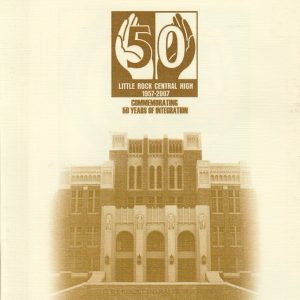

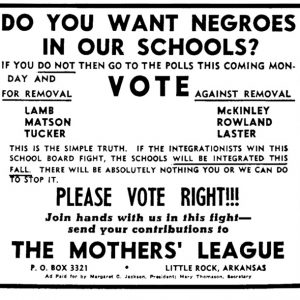

Meanwhile, across the South, resistance to desegregation grew. Nineteen U.S. senators and eighty-one congressmen, including all eight members from Arkansas, signed the “Southern Manifesto” denouncing the U.S. Supreme Court’s decision and urging Southern states to resist it. In Little Rock, the Capital Citizens’ Council—a local version of the white citizens’ councils that were emerging across Arkansas and the South—formed in 1956 to promote public resistance to desegregation. The organization purchased newspaper advertisements attacking integration and held rallies at which speakers challenged Arkansans to resist. In one of the more publicized events, Georgia Governor Marvin Griffin and former Georgia state representative and state senator Roy V. Harris, frequent speakers at white citizens’ council rallies across the South, assured listeners at a Capital Citizens’ Council fundraiser that Georgia would not allow school desegregation and called upon Arkansans to support white supremacy and defend segregation. With fall of 1957 fast approaching, both segregationists and school district officials appealed to Governor Orval Faubus to take action to preserve order. In a letter-writing campaign to the governor, segregationists predicted that violence would erupt if desegregation proceeded at Central High School. School district officials appealed to the governor to assure the public that desegregation would proceed smoothly. Faubus, in turn, asked the federal government for assistance in the event of trouble. Arthur B. Caldwell, head of the Department of Justice’s civil rights division, met with Faubus on August 28, 1957, and advised him that the federal government could not promise advance responsibility for maintaining order. Angered when the press received a report of the meeting, Faubus told reporters that the federal government was trying to force integration on an unwilling public while at the same time demanding that states handle any problems that might arise on their own.

Closely aligned with the Capital Citizens’ Council, the Mothers’ League of Central High, formed by Margaret Jackson and Nadine Aaron in August, petitioned the governor to prevent desegregation at the school. The group filed a petition on August 27, 1957, seeking a temporary injunction against integration. Pulaski Chancellor Murray Reed granted the injunction on the grounds that desegregation could lead to violence. The next day, however, Federal District Judge Ronald Davies nullified the injunction and ordered the Little Rock School Board to proceed with its desegregation plan. The conflict reached crisis proportions when Faubus appeared on television on September 2, 1957, and announced that he had called out units of the Arkansas National Guard to prevent violence at Central High School, saying, “There is evidence of disorder and threats of disorder which could have but one inevitable result—that is violence, which can lead to injury and the doing of harm to persons and property.” School district officials advised the black students who had registered at Central not to try and attend for the first day of classes on September 3. Davies ordered the school board to proceed with desegregation the next day.

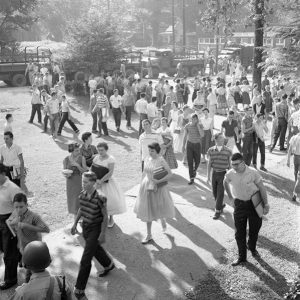

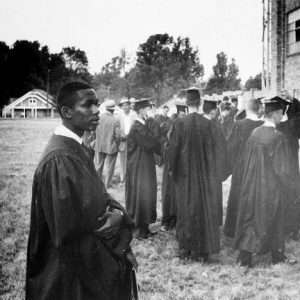

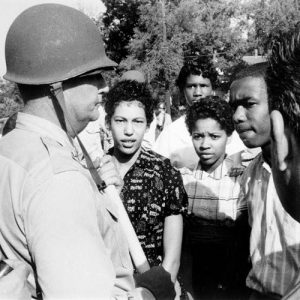

On September 4, 1957, nine Black students attempted to enter Central High School. Several of them made their way to one corner of the campus where the National Guard turned them away. One of them, fifteen-year-old Elizabeth Eckford, arrived at the north end of the campus and was directed away by National Guardsmen. She walked south down Park Street in front of the school campus, surrounded by a growing crowd of protesters who jeered and taunted her. Eckford made her way to a bus stop on the south side of the campus and was able to board a bus and get away to safety at her mother’s workplace. The next morning, people around the country and world opened their newspapers to images of the teenager besieged by an angry mob of students and adults.

The Little Rock School Board asked Davies to suspend his desegregation order temporarily, but the judge refused and ordered the school district to proceed with desegregation. The judge also instructed U.S. Attorney General Herbert Brownell Jr. to file a petition for an injunction against Faubus and two officers of the Arkansas National Guard to prevent them from obstructing the court order to desegregate. In the interim, U.S. Congressman Brooks Hays, a Democrat, arranged a meeting between Faubus and President Dwight D. Eisenhower to try and reach a solution to the crisis. They met at Eisenhower’s vacation home in Newport, Rhode Island, on September 14, but the meeting ended without an agreement.

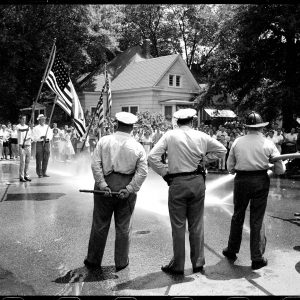

On September 20, 1957, Judge Davies ordered Faubus and the National Guard commanders to stop interfering with the court’s desegregation order. Faubus removed the guardsmen from the school and left the state for a Southern governors’ conference in Georgia. The following Monday, September 23, 1957, Little Rock police were left to control an unruly mob that quickly grew to over 1,000 people as the nine Black students entered the school through a side door. The crowd’s attention was diverted when some of the protestors chased and beat four Black reporters outside the school. By lunchtime, police and school officials feared that some in the crowd might try to storm the school and removed the nine students for their safety.

Little Rock Mayor Woodrow Mann asked the federal government for assistance, and President Eisenhower issued Executive Order 10730, sending units of the U.S. Army’s 101st Airborne Division to Little Rock and federalizing the Arkansas National Guard.

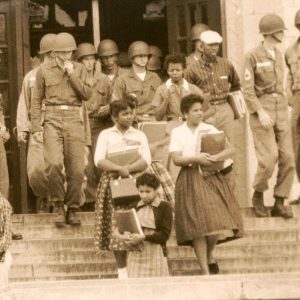

These U.S. Army troops escorted the “Little Rock Nine,” as they became known, into Central High School on September 25, 1957. After weeks of turmoil and trying to keep up with their work without attending school, the students went to their classes guarded by soldiers. Faubus appeared on television saying that Little Rock was “now an occupied territory.”

By October 1, most of the enforcement duty was turned over to the National Guard troops, and the U.S. Army troops were completely removed by the end of November. On October 25, one month after they arrived with a federal troop escort, the Little Rock Nine rode to school for the first time in civilian vehicles. While conditions calmed outside the campus, inside the school, the Nine endured an endless campaign of verbal and physical harassment at the hands of some of their fellow students for the remainder of the year. More than 100 white students were suspended, and four were expelled, during the year, raising segregationist ire against Principal Jess Matthews. One of the Nine, Minnijean Brown, was expelled in February 1958 for retaliating against the abuse; she was struck by a white student and called the student “white trash” in response.

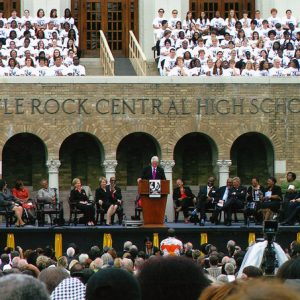

In spite of the abuse, the bomb threats, and all other disruptions to the learning environment, the only senior among the Nine, Ernest Green, became Central High’s first Black graduate on May 27, 1958. Of his experience that year, Green said, “It’s been an interesting year…. I’ve had a course in human relations firsthand.” The 1957 Central High Crisis came to symbolize both massive resistance to social change and the federal government’s commitment to enforcing civil rights for Black citizens.

Green’s graduation did not end the “crisis” in Little Rock, however. As the NAACP continued to press for continued desegregation through the federal courts, segregationist and moderate whites began a struggle of their own for control of local schools that would not end until the public high schools closed for the duration of the 1958–59 school year, what is known as the Lost Year, and finally reopened in the fall of 1959.

For additional information:

“1950s Special Report: ‘Central High School Students Speak Out on Negro Students.’” Hezakya Newz & Films. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=4JQSWsOIJA4&ab_channel=HezakyaNewz%26Films (accessed July 11, 2023).

Anderson, Karen. Little Rock: Race and Resistance at Central High School. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 2009.

———. “The Little Rock School Desegregation Crisis: Moderation and Social Conflict.” Journal of Southern History 70 (August 2004): 603–636.

Ashmore, Harry S. Civil Rights and Wrongs: A Memoir of Race and Politics, 1944–1996. Columbia: University of South Carolina Press, 1994.

Baer, Frances Lisa. Resistance to Public School Desegregation: Little Rock, Arkansas and Beyond. New York: LFB Scholarly Publishing, 2008.

Bates, Daisy. Long Shadow of Little Rock. Fayetteville: University of Arkansas Press, 1997.

Beals, Melba Pattillo. Warriors Don’t Cry: A Searing Memoir of the Battle to Integrate Little Rock’s Central High. Little Rock: Washington Square Press, 1994.

“Blogging the Digitization of the History of Segregation and Integration of Arkansas’s Educational System.” Digital collection. University of Arkansas at Little Rock Center for Arkansas History and Culture. https://ualrexhibits.org/roadblog/ (accessed August 17, 2022).

Bowman, Michael Hugh. “In the Eye of the Beholder: The Little Rock Central Crisis as a Television Event.” PhD diss., Arkansas State University, 2008.

Brückmann, Rebecca. Massive Resistance and Southern Womanhood: White Women, Class, and Segregation. Athens: University of Georgia Press, 2021.

———. “Pointing Fingers? Massive Resistance and German Reactions to the Little Rock Crisis, 1957.” Southern Quarterly 58 (Spring 2021): 34–54.

Central High Desegregation Crisis Video Clips. 1957–1959. Video from Home Movie Collection, BC.AV.09.23, Butler Center for Arkansas Studies, Bobby L. Roberts Library of Arkansas History & Art, Central Arkansas Library System: Central High Video Clips (accessed July 11, 2023).

Choi, Connie H. “’A Matter of Building Bridges’: Photography and African American Education, 1957–1972.” PhD diss., Columbia University, 2019.

Collins, Cathy J. “Forgetting and Remembering: The Desegregation of Central High School in Little Rock, Arkansas: Race, Community Struggle, and Collective Memory.” PhD diss., Fielding Graduate Institute, 2004.

Collins, Janelle. “Easing a Country’s Conscience: Little Rock’s Central High School in Film.” Southern Quarterly 46 (Fall 2008): 78–90.

“Confronting the Crisis: The Legacy of Little Rock Central High School.” Digital collection. University of Arkansas at Little Rock Center for Arkansas History and Culture. https://ualrexhibits.org/legacy/ (accessed September 4, 2025).

Cope, Graeme. “‘Dedicated People’: Little Rock Central High School’s Teachers during the Integration Crisis of 1957–1958.” Arkansas Historical Quarterly 70 (Spring 2011): 16–44.

———. “‘Everybody Says All Those People… Were from out of Town, But They Weren’t’: A Note on Crowds during the Little Rock Crisis.” Arkansas Historical Quarterly 67 (Autumn 2008): 245–267.

———. “‘Honest White People of the Middle and Lower Classes’? A Profile of the Capital Citizens’ Council during the Little Rock Crisis of 1957.” Arkansas Historical Quarterly 61 (Spring 2002): 37–58.

———. “‘A Thorn in the Side’? The Mothers’ League of Central High School and the Little Rock Desegregation Crisis of 1957.” Arkansas Historical Quarterly 57 (Summer 1998): 160–190.

Corrigan, Lisa M. “The (Re)segregation Crisis Continues: Little Rock Central High at Sixty.” Southern Communication Journal 83.2 (2018): 65–74.

Devlin, Erin Krutko. “‘Justice Is a Perpetual Struggle’: The Public Memory of the Little Rock School Desegregation Crisis.” PhD diss., College of William and Mary, 2011. Online at https://scholarworks.wm.edu/etd/1593092083/ (accessed July 11, 2023).

———. Remember Little Rock. Amherst: University of Massachusetts Press, 2017.

Eisenhower, David, and Alex Eisenhower. “A Civil Legacy: A Judiciary History of the Central High School Crisis.” FRANK, Fall/Winter 2007, 35–45.

Ellis, Kara D. “Assuming Responsibility: The Little Rock Branch of the American Association of University Women and the Little Rock School Desegregation Crisis.” MA thesis, University of Little Rock, 2009.

“Fifty Years Later.” Special issue, Arkansas Times. September 20, 2007.

Fisher, Shawn A. “The Battle of Little Rock.” PhD diss., University of Memphis, 2013.

Freyer, Tony. The Little Rock Crisis: A Constitutional Interpretation. Westport, CT: Greenwood Press, 1948.

———. Little Rock on Trial: Cooper v. Aaron and School Desegregation. Lawrence: University Press of Kansas, 2007.

Godfrey, Phoebe. “Bayonets, Brainwashing, and Bathrooms: The Discourse of Race, Gender, and Sexuality in the Desegregation of Little Rock’s Central High.” Arkansas Historical Quarterly 62 (Spring 2003): 42–67.

Harper, Misti. “And They Entered as Ladies: When Race, Class and Black Femininity Clashed at Central High School.” PhD diss., University of Arkansas, 2017. Online at https://scholarworks.uark.edu/etd/2405/ (accessed July 11, 2023).

Huckaby, Elizabeth. Crisis at Central High, Little Rock, 1957–58. Baton Rouge: Louisiana State University Press, 1980.

Jacoway, Elizabeth. Turn Away Thy Son: Little Rock, the Crisis That Shocked the Nation. New York: Free Press, 2007.

Jacoway, Elizabeth, and C. Fred Williams, eds. Understanding the Little Rock Crisis: An Exercise in Remembrance and Reconciliation. Fayetteville: University of Arkansas Press, 1999.

Katagiri, Yasuhiro. Black Freedom, White Resistance, and Red Menace: Civil Rights and Anticommunism in the Jim Crow South. Baton Rouge: Louisiana State University Press, 2014.

Kirk, John A. Beyond Little Rock: The Origins and Legacies of the Central High Crisis. Fayetteville: University of Arkansas Press, 2007.

———. Redefining the Color Line: Black Activism in Little Rock, Arkansas, 1940–1970. Gainesville: University Press of Florida, 2002.

Kirk, John A., ed. An Epitaph for Little Rock: A Fiftieth Anniversary Retrospective on the Central High Crisis. Fayetteville: University of Arkansas Press, 2008.

Kruse, Nyssa. “From 1957 to 2023: How the Supreme Court Prevented Little Rock Schools from Achieving the Ideal of Desegregation.” Indiana Journal of Law and Social Equality 13, no. 1 (2025): 14–68. Online at https://www.repository.law.indiana.edu/ijlse/vol13/iss1/3/ (accessed November 21, 2025).

LaNier, Carlotta Walls, and Lisa Frazier Page. A Mighty Long Way: My Journey to Justice at Little Rock Central High School. New York: One World/Ballantine, 2009.

Lewis, Catherine M., and J. Richard Lewis, eds. Race, Politics, and Memory: A Documentary History of the Little Rock School Crisis. Fayetteville: University of Arkansas, 2007.

“The Little Rock Crisis: A Fiftieth Anniversary Retrospective.” Special issue, Arkansas Historical Quarterly 66 (Summer 2007).

Margolick, David. Elizabeth and Hazel: Two Women of Little Rock. New Haven, NJ: Yale University Press, 2011.

Nichols, David. A Matter of Justice: Eisenhower and the Beginning of the Civil Rights Revolution. New York: Simon & Schuster, 2007.

Ogden, Dunbar H. My Father Said Yes: A White Pastor in Little Rock School Integration. Nashville, TN: Vanderbilt University Press, 2008.

Özdemír, Fatma Doğuş. “Red, White, and Black: Anti-Communism, Massive Resistance, and the Case of Orval Faubus.” MA Thesis, Bilkent University, 2008.

Perry, Ravi K., and D. LaRouth Perry. The Little Rock Crisis: What Desegregation Politics Says about Us. New York: Palgrave Macmillan, 2015.

Pierce, Michael. “Historians of the Central High Crisis and Little Rock’s Working-Class Whites: A Review Essay.” Arkansas Historical Quarterly 70 (Winter 2011): 462–483.

———. “Odell Smith, Teamsters Local 878, and Civil Rights Unionism in Little Rock, 1943–1965.” Journal of Southern History 84 (November 2018): 925–958.

Reed, Roy. Faubus: The Life and Times of an American Prodigal. Fayetteville: University of Arkansas Press, 1997.

“The Road from Hell Is Paved with Little Rocks.” Digital collection. University of Arkansas at Little Rock Center for Arkansas History and Culture. https://ualrexhibits.org/desegregation/ (accessed September 4, 2025).

Roberts, Terrence. Lessons from Little Rock. Little Rock: Butler Center Books, 2009.

Robinson, Brandon Earl. “The Band at Little Rock Central High School Before, During, and After Integration in 1957–1958.” PhD diss., University of Mississippi, 2014.

Roy, Beth. Bitters in the Honey: Tales of Hope and Disappointment across Divides of Race and Time. Fayetteville: University of Arkansas Press, 1999.

“Special Issue: 40th Anniversary of the Little Rock School Crisis.” Special issue, Arkansas Historical Quarterly 56 (Autumn 1997).

West, Michael O. “Little Rock as America: Hoyt Fuller, Europe, and the Little Rock Racial Crisis of 1957.” Journal of Southern History 78 (November 2012): 913–942.

“The Whole World Was Watching.” Special issue. Arkansas Times, September 19, 1997.

National Park Service

Central High School National Historic Site

Irene Samuels told me at a meeting for the planning of the 40th reunion of the Women’s Emergency Committee (WEC) that I was to arrange for an artwork to commemorate the contributions of the committee. She just pointed a finger at me and said that was my assignment. I was not quite sure what she had in mind, but after thinking about it for a few days, I decided to create the “windows project.” The membership of the WEC was not known to the community. And many were relieved that their names were not made public. Members of the WEC board had often suffered in their efforts to carry out the organization’s mission. Inspired by Maya Lin’s naming project, I decided to have the names of WEC members etched on the windows of the sun room, a space adjacent to the dining room of Mrs. Terry’s home, where board members had once gathered around the dining room table to conduct their business. Soos Glass Co. was hired to etch the names of WEC members, never before made public, on replacement window panes. As was usual at the time, women were identified by their husbands’ names. Only unmarried women were listed by their given names. So it was that the the membership of WEC was revealed on the occasion of the 40th anniversary of WEC. (I also served as chair of WEC’s 40th Commemoration Committee.) Hillary Clinton was the featured speaker.

At Springdale High School, we had a student from Central during the 1958-59 year (William Branscom). His father was a dentist in Little Rock. He commuted from Little Rock each week. He stayed with relatives, the Sisco family in Springdale, during that time, owners of the funeral home there. He was killed in a car accident at a Northwest Arkansas car rally. Jerry Don May was a 1959 graduate of Springdale High School; he attended Springdale High while the Little Rock schools were closed. He had a younger sister who also attended that year.

This book also discusses the Little Rock incident:

Scott E. Buchanan. Some of the People Who Ate My Barbecue Didn’t Vote for Me: The Life of Georgia Governor Marvin Griffin. Nashville, TN: Vanderbilt University Press, 2011.