calsfoundation@cals.org

David Williamson Carroll (1816–1905)

David Williamson Carroll, who was one of the eleven men who represented the state in the Confederate Congress, was the first Roman Catholic to represent Arkansas in a national legislative body. He was one of the three members of the eleven-member Arkansas delegation who owned no slaves.

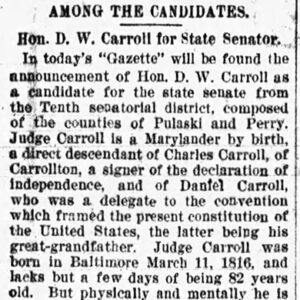

David Williamson Carroll was born in Baltimore, Maryland, on March 11, 1816, the eldest child of William Carroll and Henrietta Maria Williamson. He was the scion of a prominent Catholic family. His great-grandfather Daniel Carroll (1730–1796) participated in the Constitutional Convention of 1787, being one of the three members of the Maryland delegation to sign the document. Daniel Carroll was the older brother of John Carroll (1735–1815), the first Catholic bishop and archbishop of Baltimore, and the founding father of the American hierarchy. These Carrolls were also distant cousins of Charles Carroll (1737–1832), the only Catholic to sign the American Declaration of Independence.

Carroll was educated at St. Mary’s College in Baltimore. At the age of twenty, he journeyed to Arkansas to work for a surveying company. He returned two years later to Maryland, where he married Melanie Mary Scull in 1838. They had seven children, though apparently only three lived to adulthood. Melanie Carroll died on February 11, 1869.

Carroll returned to Arkansas sometime in the early 1840s, settling in Little Rock (Pulaski County). Andrew Byrne, the first Catholic bishop for the Diocese of Little Rock, resided at Carroll’s home in the Arkansas capital before the first St. Andrew’s Cathedral and Rectory were completed in 1846. That year, President Polk appointed Carroll deputy clerk for the U.S. District Court in Little Rock. Two years later, Carroll was admitted to the Arkansas bar. In 1850, Carroll ran successfully for the Arkansas House of Representatives. Carroll served only one two-year term, but the Know-Nothing American party attacks on Catholics in the mid-1850s only solidified his identification with Arkansas’s Democrats. By 1860, Carroll had relocated to Pine Bluff (Jefferson County) to serve as prosecuting attorney for the district that covered southeastern Arkansas.

With the onset of the Civil War, Carroll resigned his position as prosecuting attorney in the spring of 1862 to organize Confederate volunteers, who soon joined the Eighteenth Arkansas Infantry. He was stationed at Fort Pillow, Tennessee, and Corinth, Mississippi; at the latter post, the Arkansans contracted yellow fever and left the military in August 1862, and Carroll returned to Pine Bluff.

A unicameral Provisional Congress initially wrote the Confederate Constitution and selected its president and vice president in early 1861. In November, voters elected Jefferson Davis to a six-year term as president. They also elected members to a Congress composed of a Senate and a House of Representatives. Each state was granted two senators. Arkansas had four Confederate congressional districts, one for each quadrant of the state. Another election in November 1863 elected the second and final Confederate Congress.

In September 1864, Confederate senator Charles B. Mitchel died, and the legislature elevated Third District representative Augustus H. Garland to the upper house. His district covered Little Rock and southeastern Arkansas. By late 1864, however, Federal forces had overrun the northern two-thirds of the state, including the capital city of Little Rock. As reported in the Washington (Hempstead County) Telegraph on December 7, 1864, Carroll won a special election to the vacant seat. By this time, traveling to the Confederate capital was not easy, as the Union had control of the Mississippi River. Carroll made it to Confederate House of Representatives on January 11, 1865, yet that body would exist for only two more months. During his short tenure, Carroll supported most desperation methods, with the exception of higher taxes and the arming of slaves. He supported granting more power to the Confederate government and was against any peace proposal with the North. Carroll was one of three Arkansans who were still at their desks when the Confederate Congress adjourned forever on March 18, 1865. (Both Senators and one House member were not there.)

After the war, Carroll was chosen as probate judge for Jefferson County in 1866, but he was removed by the Republican government two years later. In 1878, Carroll was named state chancery circuit judge, a position he held until he retired in 1890. He died in Little Rock on June 24, 1905, and his remains are in the Calvary Catholic Cemetery.

Carroll lived longer than any former member of the Confederate Congress, the only one to see the twentieth century. Of all the eleven Arkansas Confederate congressmen, Carroll was the only one whose views on secession prior to the war could not be uncovered by historians Thomas Alexander and Richard Beringer.

For additional information:

Alexander, Thomas, and Richard Beringer. The Anatomy of the Confederate Congress: A Study of the Influences of Member Characteristics on Legislative Voting Behavior, 1861–1865. Nashville, TN: Vanderbilt University Press, 1972.

Journal of the Congress of the Confederate States of America, 1861–1865. 7 Vols. Washington DC: Government Printing Office, 1904–1905.

Warner, Ezra J., and W. Buck Yearns. Biographical Register of the Confederate Congress. Baton Rouge: Louisiana State University Press, 1975.

Woods, James M. “Devotees and Dissenters: Arkansans in the Confederate Congress, 1861–1865.” Arkansas Historical Quarterly 38 (Autumn, 1979): 227–247.

———. Rebellion and Realignment: Arkansas’s Road to Secession. Fayetteville: University of Arkansas Press, 1987.

James M. Woods

Georgia Southern University

Carroll Endorsement Article

Carroll Endorsement Article

Comments

No comments on this entry yet.