calsfoundation@cals.org

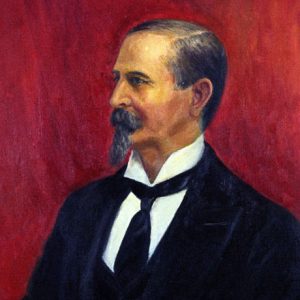

Daniel Webster Jones (1839–1918)

Nineteenth Governor (1897–1901)

Daniel Webster Jones was the last Civil War veteran to serve as governor of Arkansas. He was a member of the old, aristocratic, land-owning class in the South. Most of the Arkansas governors of his genteel social rank had stood loyally by the interests of the wealthier landowners and businessmen, but Jones, as governor, tended to give more attention to the interests of the poorer farming class. Those who wanted still more radical reform in the interests of the lower classes had formed the Populist Party in the early 1890s. This new party threatened the dominance of the one-party system, and thus white supremacy. To stave off the movement of voters away from the Democratic Party, Jones cautiously moved toward agrarian reform, but he stopped short of the more dramatic grandstanding agrarian style reform of his successor, Governor Jeff Davis.

Daniel Jones was born on December 15, 1839, in Bowie County, Texas, to Isaac N. Jones, a physician and member of the Texas Republic Congress, and Elizabeth W. Littlejohn. Jones was one of nine children. In 1840, while Jones was still an infant, the family moved to the Arkansas town of Washington (Hempstead County), and Jones’s father purchased a large plantation in Lafayette County. Jones attended the Washington Academy, which was conducted by B. J. Borden. He grew up with all the advantages that come from being part of an aristocratic and wealthy family. After graduating from the academy, Jones began studying law in January 1860, but when Arkansas seceded from the Union in May 1861, he enlisted in the Third Arkansas Regiment (State Troops). Fighting under Colonel John R. Gratiot, he participated in the Battle at Wilson’s Creek, Missouri, on August 10, 1861. He fought at Corinth, Mississippi, on October 4, 1862. There, he was shot just below the heart and was taken prisoner by Union forces; he was later exchanged by the Union for one of their own troops. At the Battle of Vicksburg in July 1863, he was again briefly held as a prisoner. By this time, Jones had achieved the rank of colonel.

After being released from his second internment by the Union forces, and while the war continued, Jones and Margaret P. Hadley of Hamburg (Ashley County) married on February 9, 1864, after a brief, two-week courtship. They had two daughters and three sons. After his marriage, Jones continued as the commander of his regiment until nearly the final days of the war. He returned to Washington to resume his study of law and, in September 1865, was admitted to the bar. The following January, Governor Isaac Murphy appointed him prosecuting attorney for Hempstead County. During the 1870s, he practiced law in partnership with James K. Jones (no relation), a future United States senator. They had lived only six miles apart in Hempstead County, were boyhood friends, and grew up in the same comfortable upper-class environment.

Daniel Jones was elected prosecuting attorney for the Ninth Judicial Circuit in 1874, served as a Democratic presidential elector in 1876 and 1880, and won the office of attorney general in the 1884 and 1886 elections. As attorney general, he used his office to protect railroad interests. After practicing law in Little Rock (Pulaski County) for several years, Jones was elected in 1890 to serve a term in the state House of Representatives for Pulaski County. Jones did not demonstrate a tendency at that time to compromise with the rising populistic sentiment. He opposed concession to the demands of the populists for reform of the election laws. Instead, he voted for an election law that weakened the opposition parties. In 1895, he was hired by the Iron Mountain Railroad to serve as a lobbyist. In this position, he fought against the creation of a railroad commission. The railroads feared reduction of their rates because of the angry demands of farmers. As governor, Jones was more willing to meet the demands of the farmer’s protest movement. He would fight for both a railroad commission and fair election laws.

In 1896, he entered the county primaries as a candidate for the Democratic gubernatorial nomination. Despite his image as a planter-class candidate and railroad attorney, he now proposed some of the same reforms favored by the agrarian agitators. Although the Populist Party did not show great strength in Arkansas elections, some of the reform sentiments of that party did gain support from the state’s large rural class. Jones hoped to avoid any drift away from the Democratic Party.

Silver became the leading issue in the 1896 campaign in Arkansas and the nation, and Jones, establishing himself as the most aggressively pro-silver candidate, won the state primary. The Southern and Western states especially supported the coinage of silver as a means of inflating the currency. The more agrarian states looked upon the gold standard as a way for eastern bankers and businessmen to gain a financial advantage over the rest of the nation. The national Democratic Party nominated William Jennings Bryan as their candidate. He believed that allowing the monetization of silver would help oppressed debtor farmers. An inflated currency would raise the price of farm products and would in real terms lower mortgage payments. The issue was divisive within the Democratic Party nationally and in Arkansas as well. Jones made bold attacks on the conservative gold standard politicians in his party. His pro-silver stance helped him win the Democratic primary election. In the general election in September, Jones easily defeated Republican candidate Harmon L. Remmel, receiving 91,114 votes compared to Remmel’s 35,836. The Populist Party candidate, A. W. Files, received only 13,990. The Populist Party faded quickly from the scene after the 1896 election.

In his inaugural address on January 18, 1897, Jones called on the General Assembly to reform the election laws to provide fairer treatment for the minority (Republican) party. The assembly rejected this and most of the other reform measures suggested by Jones. The House of Representatives approved his proposal for a railroad commission, a measure aimed at lowering railroad rates so that farmers could ship their goods to market at reasonable rates. The more conservative Senate rejected the measure.

Disappointed with the regular legislative session’s lack of productivity, Jones called a special session to meet on April 26, 1897. The governor had called in his inaugural address for the building of a state-owned railroad system. Coal mine operators in Arkansas believed that railroad monopolies kept their transportation costs unfairly high. The agrarians across the nation as well as in Arkansas also believed the railroads were charging too much for shipment of farm commodities. Populist sentiment in the Arkansas legislature prompted passage of the Bush Act, which provided for creation of a state-owned railroad which could force fairer railroad competition. But the financing scheme did not raise sufficient money to begin construction. Arkansas never built the railroad, and the 1899 legislature repealed the Bush Act. The most important railroad measure from the governor’s viewpoint was the commission bill, a regulatory measure, but the pro-railroad forces, continuing their domination of the Senate, killed it. Despite these failures, Jones is regarded as one of the earliest governors of the state to exhibit progressive leanings.

In the fall of 1898, Jones easily defeated Republican H. F. Auten and won a second term. Although the Bush Act and the hopes for lowering freight rates through a state-owned railroad were dead, Jones won a major victory when the legislature finally enacted a railroad commission bill in March 1899. Farmers and other industries dependent upon the railroad to ship their goods were crying for lower railroad freight rates. At first, some of these shippers actually experienced higher rates, but by 1901, the commission claimed it had achieved an overall lowering of rates. There is no evidence to support their claim, and more effective rate legislation would only come from the U.S. Congress with the passage of the Hepburn Act in 1906.

The governor continued his drift toward populist reforms by calling for passage of a bill to control corporate monopolies. The General Assembly responded by passing the Rector Antitrust Act. This law made it illegal for monopolies (non-competitive corporations) to operate in the state. Newly elected attorney general Jeff Davis tried to win support by aggressively enforcing the new act, threatening to take the monopolies to court. Because of his threats, many insurance companies fled the state. Jones considered Davis’s behavior as simply an attempt to appeal to the prejudices of the masses to win votes, and a serious division developed between the two men.

The Jones administration generated another controversy that raged for a decade. The governor repeated former governor James P. Clarke’s request that the Old State House be replaced by a new capitol; the old building had grace and charm but insufficient space. Davis initiated a frenzied legal campaign in May 1899 to obstruct the project, which he viewed as wasteful. Jones managed to lay the cornerstone in November 1900, but the construction site remained inactive for two years.

On January 29, 1900, Jones announced his candidacy for the United States Senate. In his support for American expansion overseas, he stood squarely in opposition to the other candidate, United States senator James H. Berry. Daniel Jones lost the primary election.

Jones turned his energies toward the practice of law in Little Rock. His political star was rapidly eclipsed by Jeff Davis’s rise. After his wife’s death in 1913, he returned briefly to active political office as Pulaski County representative in the 1915 assembly.

After a brief bout with pneumonia, Jones died at Little Rock on Christmas Day of 1918 and was buried in a uniform of Confederate gray at Oakland Cemetery in Little Rock.

For additional information:

Donovan, Timothy P., Willard B. Gatewood Jr, and Jeannie M. Whayne, eds. The Governors of Arkansas: Essays in Political Biography. 2d ed. Fayetteville: University of Arkansas Press, 1995.

Herndon, Dallas T., ed., Centennial History of Arkansas. Vol. 1. Chicago: S. J. Clarke Publishing Company, 1922.

Ledbetter Jr., Calvin R. “Governor Daniel Webster Jones: An Unexpected Progressive.” Arkansas Historical Quarterly 68 (Spring 2009): 23–51.

Niswonger, Richard L. Arkansas Democratic Politics, 1896–1920. Fayetteville: University of Arkansas Press, 1990.

The Goodspeed Biographical and Historical Memoirs of Central Arkansas. Easley, SC: Southern Historical Press, 1978.

Richard L. Niswonger

John Brown University

This entry, originally published in Arkansas Biography: A Collection of Notable Lives, appears in the CALS Encyclopedia of Arkansas in an altered form. Arkansas Biography is available from the University of Arkansas Press.

Comments

No comments on this entry yet.