calsfoundation@cals.org

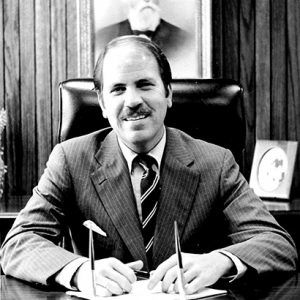

Dan Carlos West (1939–)

Dr. Dan Carlos West served as president of Arkansas College, now Lyon College, from 1972 to 1988. As stated in Brooks Blevins’s history of the college, the physical and curricular changes, along with West’s administrative style, made his presidency “the most turbulent, the most exciting, the most confusing, [and] the most successful” time in the school’s history up to that point.

Dan C. West was born on May 29, 1939, in Galveston, Texas, one of four children of Embry Carlos West and Mildred Louise Junker West. The family later moved to Dallas, Texas, where West attended Woodrow Wilson High School, graduating in 1957. He attended the University of Texas for a year and then went on to the U.S. Naval Academy. Leaving before completing a degree, he earned a BA in history at Austin College in Sherman, Texas, in 1962. His graduate studies led to a Bachelor of Divinity in Bible studies from Union Theological Seminary in 1965 and a Doctor of Divinity in systematic theology from Vanderbilt University. During his Arkansas College presidency, he also earned an EdD from Harvard University in administration, planning, and social policy.

West married Sidney Claire Childs of Anson, Texas, whom he met when both were students at Austin College; the couple had two children.

West served as the minister of Smyrna Presbyterian Church in Nashville, Tennessee, for three years. He then left the parish ministry for higher education, returning to Austin College as director of church relations. There, his interests and responsibilities grew to include leading a project to overhaul every aspect of the college, and his title became coordinator of research and development. It was from this post that he moved to Arkansas College.

In 1972, at just thirty-three years old, West was the youngest college president in Arkansas. He had assumed leadership of an institution at which one-third of the faculty did not have a terminal degree, enrollment was only around 350 students, the endowment was a minuscule $800,000, and debt was high. Many people around the country at that time believed that small private institutions like Arkansas College simply were not viable.

Brought in by a board of trustees who wanted to see academic innovation that would lead to significant enrollment growth, the new president arrived on a campus with sufficient facilities, many only a few years old, to support that kind of growth. With his arrival, West mandated a nine-month study of every aspect of the school and then developed the “New Plan.” With no campus plant concerns, West expected to lead reformation of the curriculum and continue efforts to strengthen the faculty. However, an April 1973 tornado devastated the campus, destroying an instructional building and the administration building and damaging to some extent every other building on campus except the new gymnasium and physical education building.

West’s “New Plan” was approved by the board in May 1973, and when it actually got under way, it polarized the college. By the spring of 1974, the campus was in revolt. West had added numerous career-preparation options, such as business administration, accounting, media arts, health education, secretarial administration, data processing, and hospital unit management. Students in these programs could get credit for some on-the-job training. The general education requirements were reduced from forty-four to thirty-one credit hours, and for the first time in the history of the college, no Bible course was required. Tenure was put on moratorium, merit pay increases were instituted, and some positions were cut back to part time. Some faculty demanded West’s resignation, but the trustees, who had hired him to restructure the curriculum and revitalize the college, supported his decisions.

The unrest intensified the next year, when the designers of a new academic calendar abandoned the semester system for a combination of quarters and one-month modules. Faculty had to redesign all their courses to fit this new system, and students had difficulty getting enough credits to complete degree plans. The new calendar provoked a student protest on the Wests’ lawn one night. Changes to dormitory regulations, along with requiring residential students under twenty-one to live on campus rather than in apartments out in town, further inflamed student opinion. When the College Council voted that year to return to the previous calendar, West did not fight it.

By the late 1970s, with a new dean of the faculty, the curriculum was changed again. General education requirements were revised, becoming more focused on the liberal arts, dropping many experimental and cross-disciplinary courses, and dramatically reducing the number of career-oriented majors. Several endowed chairs and the Williamson Prize for Excellence in Teaching were established to recognize and reward outstanding faculty members.

In 1981, West took a sabbatical to attend Harvard, where he worked on a doctorate in higher education. He returned with many new ideas, including plans for an international studies program, which led to the establishment of the Nichols Travel Program, funded by a gift from the Shuford Nichols family. Another innovation was Aberdeen Development Corporation, a venture into for-profit activities that benefited the college. The school also sold tax-exempt public improvement bonds, the first independent institution in Arkansas to do this. These undertakings got the attention of the state and national press, and eventually led to West’s later success in institutional advancement.

By the time he announced his resignation in 1988, West had gained national recognition for his innovative methods of finding funds to support small colleges. After some tumultuous years, enrollment of full-time students alone was above 500, and another 300 were enrolled part time. The faculty had improved dramatically in terms of earned doctorates, and the college had three endowed chairs and eight endowed professorships. Thanks to aggressive fundraising, a large bequest, and an innovative venture into for-profit activities, the endowment had risen to nearly $40 million. U.S. News and World Report had named the school one of the best small comprehensive colleges in the South.

West turned down several employment offers before finally accepting an invitation to become the president of Carroll College (now Carroll University) in Waukesha, Wisconsin, where he spent four years. He next became the vice president for college relations for Union College in Schenectady, New York. After seven years there, he became vice president for development for Swarthmore College in Pennsylvania; he retired in 2008 and moved to Atlanta, Georgia.

In the years after his departure from Arkansas College (which became Lyon College in 1994), the college formally recognized West’s efforts and successes by naming him an Honorary Alumnus in 1988 and awarding him an honorary Doctor of Sacred Theology in 1993. Lyon College asked him to return in 2015 as interim vice president for institutional advancement, a position he held through January 2016.

For additional information:

Blevins, Brooks. Lyon College 1872–2002: The Perseverance and Promise of an Arkansas College. Fayetteville: University of Arkansas Press, 2003.

“Former Lyon President Returns as Interim VP.” Arkansas Democrat-Gazette, October 11, 2015. https://www.arkansasonline.com/news/2015/oct/11/former-lyon-president-returns-interim-vp/ (accessed December 26, 2025).

Tebbetts, Diane. “The West Years: 1972–1988.” Arkansas College Office of the President, 1990.

Diane Tebbetts

Lyon College

Comments

No comments on this entry yet.