calsfoundation@cals.org

Cotton Pickers Strike of 1891

The Cotton Pickers Strike of 1891 was an ill-conceived attempt by a group of African-American sharecroppers in Lee County, perhaps loosely affiliated with the Colored Farmers’ National Alliance and Union (commonly called the Colored Famers’ Alliance), to increase the wages they received from local planters for picking cotton. By the time a white mob put down the strike, more than a dozen African Americans and one white man had been killed.

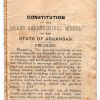

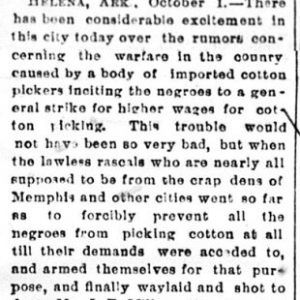

The Colored Farmers’ Alliance was founded in Texas in 1886 as the black counterpart to the Farmers’ Alliance, an all-white organization that was part of the late nineteenth-century populist, agrarian reform movement. The Colored Farmers’ Alliance spread quickly throughout the South, claiming a membership of more than one million just four years after its founding. In 1891, alliance founder and spokesman R. M. Humphrey, a white man, hatched a plan to organize a national strike of black cotton pickers in order to raise their wages. At the time, many white landowners conspired with each other to keep wages miserably low for their black workers, and local law enforcement often rounded up African Americans on vagrancy charges and forced them to work off their fines on select plantations, a practice known as peonage. Humphrey was convinced that direct action needed to be taken to combat these crimes, but many in the alliance disagreed, citing the inability of the organization to provide any protection for striking farmers. The proposed national strike date of September 12 came and went with only a handful of cotton pickers in eastern Texas withholding their labor.

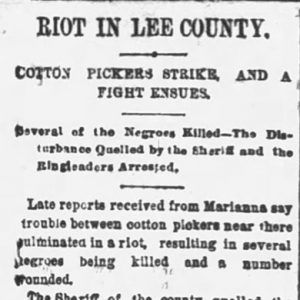

Just over a week later, however, cotton pickers in Lee County, organized by Ben Patterson of Memphis, Tennessee, went on strike after word spread that J. F. Frank, a Memphian visiting land he owned in the area, had stated that, if need be, he would pay one dollar per hundred pounds rather than the going rate of fifty cents. On September 20, cotton pickers working for Colonel H. P. Rodgers demanded an increase in their wages. Strike leaders subsequently traveled throughout the county urging others to join the movement, though with little success. In fact, conflict between strikers and non-strikers resulted in two cotton pickers being killed on September 25. In response, the county sheriff organized a posse to seek out Patterson and his followers. The situation was made worse for the strikers on September 28 after two of them killed Frank’s plantation manager, Tom Miller; another group burned down a cotton gin.

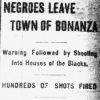

By September 29, the strikers were on the run, many of them having fled to Cat Island, located on the Mississippi River east of Horseshoe Lake (Crittenden County). The white posse stormed the island, killing two strikers and capturing nine; those captured were later seized by masked men as they were being transported to Marianna (Lee County) and subsequently hanged. Patterson managed to board a steamboat, but he, too, was killed once the crew learned his identity. By the time the mob finished suppressing the strike, it had killed fifteen African Americans and imprisoned another six.

Such deadly mob activity likely quashed future attempts at organizing landless African Americans in the area. The Cotton Pickers Strike of 1891 in some respects served as a precursor to the Elaine Massacre of 1919, revealing just how far white landowners and authorities were willing to go in order to keep local black laborers in a state of subservience and poverty so as to protect their own profits.

For additional information:

Gaither, Gerald. Blacks and the Populist Movement: Ballots and Bigotry in the New South. Tuscaloosa: University of Alabama Press, 2005.

Hild, Matthew. “Black Agricultural Labor Activism and White Oppression in the Arkansas Delta: The Cotton Pickers’ Strike of 1891.” In Race, Labor, and Violence in the Delta: Essays to Mark the Centennial of the Elaine Massacre, edited by Michael Pierce and Calvin White. Fayetteville: University of Arkansas Press, 2022.

Holmes, William F. “The Arkansas Cotton Pickers Strike of 1891 and the Demise of the Colored Farmers’ Alliance.” Arkansas Historical Quarterly 32 (Summer 1973): 107–119.

Staff of the CALS Encyclopedia of Arkansas

Labor Movement

Labor Movement Lynching

Lynching Post-Reconstruction through the Gilded Age, 1875 through 1900

Post-Reconstruction through the Gilded Age, 1875 through 1900 Race Riots

Race Riots Tate Plantation Strike of 1886

Tate Plantation Strike of 1886 Cotton Pickers Strike Article

Cotton Pickers Strike Article  Cotton Pickers Strike Article

Cotton Pickers Strike Article

Comments

No comments on this entry yet.