calsfoundation@cals.org

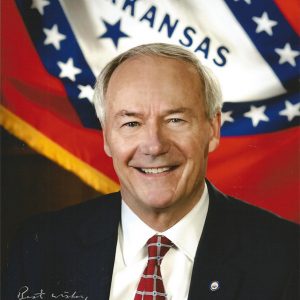

Christopher H. Harris v. Asa Hutchinson, et al.

The Arkansas constitution’s rule, commonly called “sovereign immunity,” that people cannot sue their government for damages has vexed the Arkansas Supreme Court for a century and a half, but particularly in the twenty-first century when a few justices began to insist that the ancient doctrine that “the king can do no wrong” flouted the basic human rights of Arkansans that were spelled out in the state constitution’s bill of rights. The dispute was keenly articulated in several cases that arose in the Republican-run state government in the second decade of the new century, notably the case of Christopher H. Harris v. Asa Hutchinson, et al. in 2020.

Christopher Harris sued Governor Asa Hutchinson and Patrick Fisk, the deputy director of the state Livestock and Poultry Commission. Fisk had fired him in 2018 because he had refused to hire a man (unnamed in the lawsuit) whom Hutchinson wanted to be a livestock inspector but whom Harris considered totally unqualified. Harris claimed that he was protected from retribution by the state’s whistleblower law, which encouraged government employees to expose illegal acts and waste in state agencies and institutions by protecting their careers if they did so. Harris interviewed the candidates, picked the one he thought was best qualified, and concluded that the governor’s pick was not qualified. He said he was obliged by law and policy to hire the best-qualified applicant but that, when he refused to hire Hutchinson’s candidate, he was fired the next day. Hutchinson said Harris’s charges were “factually incorrect” but did not specify how they were wrong. Circuit Judge Timothy Fox dismissed Harris’s suit on the grounds of sovereign immunity.

The Supreme Court, in a split decision, ruled that sovereign immunity—Article 5, Section 20 of the constitution, which states that “the State of Arkansas shall never be made defendant in any of her courts”—barred Harris from suing his superiors. In an opinion written by Justice Courtney Goodson, most of the justices (who were split four to three) said Harris’s accusations did not meet any of the conditions that the court had laid down in previous decisions for evading the sovereign-immunity clause or for triggering the Whistle-Blower Act. Goodson wrote that Harris’s complaint was merely “conclusory,” not providing solid evidence to back up his claims of retaliation, such as previous conversations about the hiring with either the governor or the Livestock and Poultry official. The court sent the case back to the circuit court to see if Harris could prove harm done by the governor or the Livestock and Poultry executive as individuals, not in their governmental capacities. Five months after the court’s decision, Judge Fox dismissed Harris’s suit again, concluding that he did not provide the evidence the Supreme Court required.

As was her frequent practice, Justice Josephine Hart wrote a stinging dissent. She recalled a recent and very similar case (Milligan v. Singer, 2019) involving sovereign immunity, the Whistle-Blower Act, and a Republican state executive, State Treasurer Dennis Milligan, in which Hart’s colleagues on the court refused to recognize a conflict between the sovereign-immunity clause and the state constitution’s Declaration of Rights. Sovereign immunity, she wrote, is found in the legislative article of the constitution, neither in the Declaration of Rights nor the judicial article, which suggests that it was an afterthought of the delegates to the constitutional convention of 1874.

Section 13 of the Declaration of Rights article is a sweeping and fervent assertion that people are entitled to sue whenever they are harmed and to get swift and certain justice. It makes no exception if they are harmed by the state government: “Every person is entitled to a certain remedy in the laws for all injuries or wrongs he may receive in his person, property or character; he ought to obtain justice freely, and without purchase, completely, and without denial, promptly, and without delay, conformably to the laws.” For half a century, the court had ruled that the sovereign-immunity clause, although it appeared much later in the constitution, had to be accepted as an exception to the “certain remedy” that was promised in the Declaration of Rights article in both the constitutions of 1868 and 1874.

Hart’s dissenting opinions in the Harris and Milligan cases chastised the other judges for refusing to take up the question of how sovereign immunity could be squared with two sections of the constitution’s Declaration of Rights—one that promised the right to a trial by jury for everyone who claims to be wronged or damaged in “all cases at law,” and the other (the concluding sentence of the declaration) that all the rights enumerated in the article were final and could never be amended or superseded. “We declare that everything in this article is excepted out of the general powers of the government,” the opening article of the constitution dealing with individual rights concluded. That statement has been interpreted to mean that basic human rights enumerated in the article are intrinsic and cannot be repealed or amended by the legislature or by initiative.

The majority opinion agreed that the sovereign-immunity clause could not be used to block a suit if the government officials had committed an ultra vires act—one that was beyond their authority—but said that firing an employee for insubordination was not an ultra vires act. Justice Hart said the record of the case clearly demonstrated that Harris was fired for refusing to violate public policy by hiring an unqualified person and wasting state resources. “What more should Harris have to plead to properly allege an illegal act here?” she wrote.

For additional information:

Brantley, Max. “Supreme Court Delivers Another Blow to the Arkansas Whistleblower Law.” Arkansas Times, January 9, 2020. https://arktimes.com/arkansas-blog/2020/01/09/supreme-court-deals-another-blow-to-the-arkansas-whistle-blower-law (accessed December 10, 2023).

Christopher H. Harris v. Asa Hutchinson, et al. Arkansas Judiciary. https://opinions.arcourts.gov/ark/supremecourt/en/item/459174/index.do (accessed December 10, 2023).

Moritz, John. “Justices Pare Suit by Fired Employee.” Arkansas Democrat-Gazette, January 10, 2020, pp. 1B, 3B. Online at https://www.nwaonline.com/news/2020/jan/10/justices-pare-suit-by-fired-employee-20-1/ (accessed December 10, 2023).

Wickline, Michael R. “Justices Throw out Whistleblower Suit.” Arkansas Democrat-Gazette, May 31, 2019, pp. 1B, 8B. Online at https://www.arkansasonline.com/news/2019/may/31/justices-throw-out-whistleblower-suit-2/ (accessed December 10, 2023).

Ernest Dumas

Little Rock, Arkansas

Divergent Prosperity and the Arc of Reform, 1968–2022

Divergent Prosperity and the Arc of Reform, 1968–2022 Law

Law Asa Hutchinson

Asa Hutchinson

Comments

No comments on this entry yet.