calsfoundation@cals.org

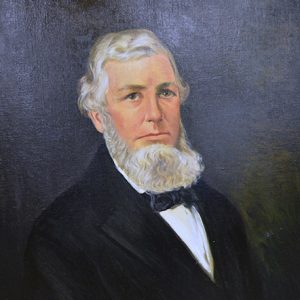

Christopher Columbus Scott (1807–1859)

Christopher Columbus Scott was appointed to the Arkansas Supreme Court after the resignation of Williamson Simpson Oldham Sr. in 1848. He was elected to the position in 1850 and reelected in 1858. He served on the Arkansas Supreme Court until his death in 1859, the longest tenure of any justice in the antebellum period.

Christopher C. Scott was born in Scottsburg, Virginia, on April 22, 1807. He was the son of General John Baytop Scott, who was a prominent lawyer and Revolutionary War soldier, and Martha “Patsy” Thompson, an accomplished daughter of a wealthy planter. John Baytop Scott was friends with many of the nation’s founding fathers, including George Washington, Thomas Jefferson, and James Madison. He was a graduate of William and Mary College and studied law under the legendary Chancellor George Wythe. John Baytop Scott was elected to the state legislature in Virginia and was commissioned as a colonel in the U.S. Army. He died just before the election of 1814. At the time of his death, he was running unopposed for Congress. His wife died three years later, leaving Christopher C. Scott an orphan at the age of eleven. He was taken in by his brother, William Scott, and his brother’s wife, Betty Scott.

Scott’s early education was entrusted to Betty Scott, who was also from a prominent Virginia family; her father was the Honorable Christopher Clarke of Bedford County. She was very active in the elite circles of Richmond, Virginia, and Washington DC society. She considered Christopher Scott her protégé, and, using her family connections, she introduced him to three U.S. presidents and many other political leaders. He was reportedly an excellent student as a youth and an avid outdoorsman, enjoying both hunting and fishing.

Scott attended Washington College (now Washington and Lee University) and graduated with highest honors in 1827. After graduation, he moved with his brother to Gainesville, Alabama, where he studied law in a local law office. After some unsuccessful business ventures, he returned to Virginia and attended Staunton Law School, where he completed his studies in July 1832.

In 1832, Scott married Elizabeth Strother Smith, the daughter of the Hon. Daniel Smith, a Virginia court of appeals judge. The couple had five children, including two sons. Their two sons would go on to fight for the Confederacy.

After law school, Scott moved back to Alabama and practiced law. In 1842, a local man of some prominence threatened Scott’s life, and Scott killed him with a double-barreled shotgun. Reports of what happened next vary, but Scott was either acquitted by a jury or pardoned by the governor. After the incident, Scott decided to leave Alabama. In 1844, he moved to Arkansas, setting up a law practice in Camden (Ouachita County). He was elected by the Arkansas General Assembly to a judgeship in the Eighth Judicial Circuit in 1846 and served until 1848, when Governor Thomas Stevenson Drew appointed him to the Arkansas Supreme Court to fill a vacancy caused by the resignation of Justice Oldham.

As a member of the Supreme Court, Justice Scott was occasionally accused of ignoring legal precedent. In the first divorce case to reach the Arkansas Supreme Court, Rose v. Rose, for example, Scott established the concept of “general indignities” as grounds for divorce. He found that legal cruelty, as then defined, was not a necessary element for the dissolution of a marriage.

In 1857, he authored an opinion that approved contingency fee arrangements in a land title dispute case know as Lytle, et al. (Cloyes’ Heirs) v. State. Up until that point, there was a common law prohibition against lawyers acquiring an interest in lands that were the subject of litigation they were working on. Scott ruled that that was no longer an accepted restriction, a decision seen as helping trial lawyers.

In 1858, Scott would write the opinion in another notable case, Gary v. Stevenson. Thomas Gary, the complainant in a freedom suit, argued that he was a white man born of a white mother and not a slave. Gary’s mother, who had a “very light complexion,” had been emancipated, and he was seeking his freedom, too. Gary had doctors testify as “experts” that “so vague are the signs of the admixture of the negro race, in one so remotely removed from the African blood by crossing with the white.” Scott found, however, that Gary must be a “negro” because his mother had not contested her bondage at the time of his birth. Therefore, her son was a slave.

In January 1859, a stagecoach came to Scott’s residence in Camden to take him to Little Rock (Pulaski County) on court business. During the trip, he acquired acute pneumonia and died on January 19, 1859, in the Anthony House in Little Rock. Scott is buried in the Scott Cemetery in Camden.

For additional information:

Christopher C. Scott Collection. Arkansas State Archives, Little Rock, Arkansas.

Hallum, John. Biographical and Pictorial History of Arkansas. Vol. 1. Albany, NY: Weed, Parson’s and Company, 1887.

Looney, J. W. “Justice Christopher Columbus Scott.” Arkansas Lawyer 49 (Fall 2014): 36.

Morris, Thomas D. Southern Slavery and the Law, 1619–1860. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 1996.

Stevenson, C. R. Arkansas Territory—State and its Highest Courts. Little Rock: Clerk of the Supreme Court, 1946.

Marty E. Sullivan

Little Rock, Arkansas

Christopher C. Scott

Christopher C. Scott

Comments

No comments on this entry yet.