calsfoundation@cals.org

Charleston (Franklin County)

County Seat

| Latitude and Longitude: | 35º17’49″N 094º02’10″W |

| Elevation: | 510 feet |

| Area: | 3.83 square miles (2020 Census) |

| Population: | 2,588 (2020 Census) |

| Incorporation Date: | May 22, 1874 |

Historical Population as per the U.S. Census:

|

1810 |

1820 |

1830 |

1840 |

1850 |

1860 |

1870 |

1880 |

1890 |

1900 |

|

– |

– |

– |

– |

– |

– |

– |

393 |

370 |

– |

|

1910 |

1920 |

1930 |

1940 |

1950 |

1960 |

1970 |

1980 |

1990 |

2000 |

|

576 |

734 |

851 |

958 |

968 |

1,036 |

1,497 |

1,748 |

2,128 |

2,965 |

|

2010 |

2020 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

2,494 |

2,588 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Charleston is one of the two county seats of Franklin County, along with Ozark. Located south of the Arkansas River, it is twenty-five miles east of Fort Smith (Sebastian County), near the coal and gas fields of northwest Arkansas, and roughly a mile from one corner of Fort Chaffee. Charleston is most known for being the first community in a southern state to desegregate its school system following the U.S. Supreme Court’s 1954 Brown v. Board of Education of Topeka, Kansas decision.

Louisiana Purchase through Early Statehood

Land south of the Arkansas River in western Arkansas was ceded to the United States by the Quapaw in 1818, granted to the Choctaw in 1820, and ceded back to the United States in 1825. White settlement in this area was not legal before land surveying was completed in 1842, but numerous squatters were already living there by that time. Thomas A. Aldridge, who served as Franklin County judge from 1840 to 1846, was a land speculator who eventually owned a plantation house and more than 5,000 acres in the area that became Charleston.

Charles Town, as it was then named, was settled in the 1840s by James B. Thaxton, Robert C. Thaxton, and Charles R. Kellam, among others. Kellam, for whom the town was named, was a Free Will Baptist preacher who came to Arkansas from Massachusetts. He operated a general store and, on August 10, 1846, was officially appointed as the first postmaster for Charleston. He also organized the Baptist church in 1846.

In 1854, A. J. Singleton established the A. J. Singleton Overland Stage stop, part of the route of the Butterfield Overland Mail Company line that connected Memphis, Tennessee, to Fort Smith. Some of the mail arrived in Charleston on this line.

In 1853, John M. Pettigrew, a professor of mathematics, along with E. M. Northrum, taught in a log structure located on the northwest end of where the modern-day fairgrounds and park are located. Pettigrew and Northrum established the Charleston Academy in 1855. It was the first school in Charleston to be run on a regular basis and was financed through a subscription plan. The academy building also housed the local Masonic lodge. In 1860, the academy had 100 pupils and three teachers.

The Union Church was built in 1860 on the site at the northwest intersection of Church and Main streets, and it had a Sunday school for all denominations, including the Presbyterian, Methodist, Baptist, and Christian (Campbellite) congregations.

Civil War through Reconstruction

During the war, Charleston was a traffic area for both Federals and Confederates and became a center for guerrilla warfare. Aldridge took some of his slaves and went to Texas, where he leased some land to farm. Sometime during the Civil War, the Aldridge plantation home and its contents were burned. Two Confederate companies were organized in the Charleston area, and both participated in several key engagements of the war.

On the morning of January 14, 1863, Union officer Colonel Martin D. Hart, leading a jayhawking guerrilla group of about forty cavalrymen, approached the area with a list of the leading men of Charleston, whom they targeted. They killed Edmond Richardson, who owned most of the land upon which Charleston was later built, as well as Colonel DeRosa Carroll before being captured at Smedley’s Mill southwest of Charleston by Lieutenant Colonel Richard Phillip Crump’s troops, who were sent by General Frederick Steele to end Hart’s attacks. Hart and two of his officers were taken to Fort Smith and hanged in the yard of the federal court.

By the time of the Civil War, there were three merchandise stores, a combination gin and mill, and several residences in the town of Charleston. In 1863, Federal scouts burned all the buildings and residences of the town except two. That same year, the Charleston Academy closed. A skirmish involving guerrilla bands associated with both sides of the war took place near Nixon’s graveyard east of Charleston on April 4, 1864.

After the war ended, citizens returned to rebuild Charleston. Several stores were in place already in 1866. In 1870, the town was laid out. That same year, Masonic Lodge No. 155 made plans to build a two-story frame structure that would house the Masonic lodge and the Charleston Masonic Institute, a school that lasted until the state of Arkansas established public schools in the area. The city was incorporated in 1874.

Post Reconstruction through the Gilded Age

Sacred Heart Catholic Church began meeting in 1877, and parishioners built their own building in 1880. Charleston’s first newspaper, The Vindicator, began publication on June 18, 1881. Sometime later, it was called the Charleston Reporter.

Because Franklin County was divided in half by the Arkansas River, the state legislature established an additional county seat at Charleston in 1885. Franklin County is one of ten counties in Arkansas to have dual seats. The first courthouse in Charleston was a native stone, two-story building on the southeast intersection of Main and Logan streets. Charleston High School’s first baccalaureate services were held on April 14, 1895.

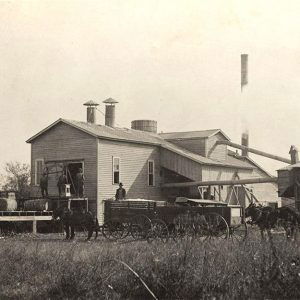

The Arkansas Central Railroad, connecting Charleston to Fort Smith, was completed around 1898. Because cotton was an important crop and coal mining contributed a good part of the area’s economy, the railroad was a boon. In 1898, there were three cotton gins in Charleston.

Early Twentieth Century

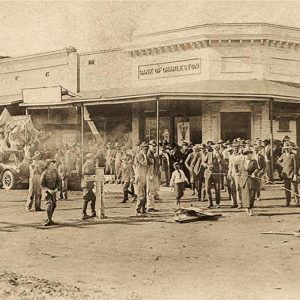

In 1900, the Charleston Express began publication. A telephone office was established in Charleston two blocks south of Main Street on South Logan Street. In 1901, the Crescent Drug Store was founded. Three years later, the Bank of Charleston was organized, and, in 1905, a teacher’s school was established. The German-American Bank opened on June 10, 1910, but changed its name to the American State Bank during World War I. The city celebrated the completion of a hard-surface road in 1929 with a parade.

The American State Bank survived difficult economic times as the farms around Charleston were devastated by the Flood of 1927 and by the Drought of 1930–1931. The bank also survived the stock market crash of 1929 and the bank holiday of March 1933. Eventually it was acquired by Simmons Bank.

World War II through the Faubus Era

The construction of Camp Chaffee (later Fort Chaffee) at the start of World War II provided jobs to area workers even as many of the men of the area were preparing to serve in the armed forces. After the war, the city sought to modernize as the economy of the area became increasingly diverse, including agriculture, timber and wood products, coal mining, steel making, and the development of the natural gas industry. The growth of the poultry industry in northwest Arkansas also provided jobs to area workers.

In 1954, days after the Supreme Court declared segregated schools unconstitutional, the Charleston school board quietly voted to close the Rosenwald school in their district and to cease transporting African-American high school students to Fort Smith. Eleven black students joined 480 white students in the Charleston school system at the end of that summer, but the desegregation in Charleston did not receive the public attention that was given to Hoxie (Lawrence County) schools in 1955 or Little Rock (Pulaski County) schools in 1957.

Modern Era

Charleston native Dale Bumpers was elected governor of Arkansas in 1970. After serving two terms, he was elected to the U.S. Senate, where he represented Arkansas from January 1975 until January 1999. Charleston is also the childhood home of author Francis Irby Gwaltney.

In the twenty-first century, Charleston remains a growing and active city of western Arkansas. It has twenty churches and more than thirty-five businesses. The Charleston school system consists of an elementary school, middle school, and high school. Total enrollment in 2010 was 888. Charleston is home to the Belle Museum and Chapel; the museum contains many historical artifacts from southern Franklin County, while the chapel, built in 1920, continues to be used as a church and is also a popular site for weddings.

In 2024, the state bought an 815-acre property in Charleston for the construction of a new 3,000-bed prison facility.

For additional information:

City of Charleston, Arkansas. http://www.aboutcharleston.com/ (accessed April 15, 2022).

Goodspeed’s History of Northwest Arkansas. Chicago: Goodspeed Publishing Company, 1889.

Shropshire, Lola. Franklin County. Charleston, SC: Arcadia, 2000.

Mary Bell Ervin

Charleston High School

Staff of the CALS Encyclopedia of Arkansas

Baptist Convention

Baptist Convention  Belle Museum

Belle Museum  Bumpers, Bumpers, Parker, and Ferguson

Bumpers, Bumpers, Parker, and Ferguson  Catholic Church

Catholic Church  Charleston Area

Charleston Area  Charleston Baseball Team

Charleston Baseball Team  Charleston Cemetery

Charleston Cemetery  Charleston Church

Charleston Church  Charleston Church

Charleston Church  Charleston City Hall

Charleston City Hall  Charleston Community Center

Charleston Community Center  Charleston Cotton Gin

Charleston Cotton Gin  Charleston Fire Department

Charleston Fire Department  Charleston High School

Charleston High School  Charleston Home

Charleston Home  Charleston Hospital

Charleston Hospital  Charleston Legion Hut

Charleston Legion Hut  Charleston Middle School

Charleston Middle School  Charleston Post Office

Charleston Post Office  Charleston School Building

Charleston School Building  Charleston Silo

Charleston Silo  Charleston Smith

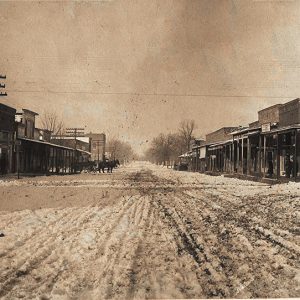

Charleston Smith  Charleston Street Scene

Charleston Street Scene  Charleston Street Scene

Charleston Street Scene  Charleston Street Scene

Charleston Street Scene  Charleston Street Scene

Charleston Street Scene  Charleston Street Scene

Charleston Street Scene  Charleston Thrasher

Charleston Thrasher  Coal Mining

Coal Mining  Franklin County Courthouse

Franklin County Courthouse  Franklin County Courthouse, Southern District

Franklin County Courthouse, Southern District  Franklin County Courthouse, Southern District

Franklin County Courthouse, Southern District  Franklin County Map

Franklin County Map  Francis Gwaltney

Francis Gwaltney  Home Economics Cottage

Home Economics Cottage  Ice Plant

Ice Plant  "Shooting the Anvils" at Charleston

"Shooting the Anvils" at Charleston

Comments

No comments on this entry yet.