calsfoundation@cals.org

Capitol-Main Historic District

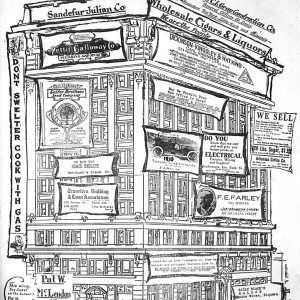

Listed on the National Register of Historic Places on April 2, 2012, the Capitol-Main Historic District in downtown Little Rock (Pulaski County) was the commercial core of the city in the early to mid-twentieth century. The district originally encompassed the 500 block of Main Street, the 100–200 blocks of West Capitol Avenue, the 500 block of Center Street, and the 100–200 blocks of West 6th Street; a boundary increase in 2024 added the buildings at 609 and 615 Main Street. Following its decline in the latter half of the twentieth century, it has been the focus of revitalization projects to resuscitate the once thriving district.

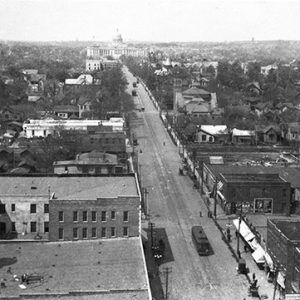

The prime location of what became the Capitol-Main Historic District was responsible for its success. Little Rock became the capital of the Arkansas Territory in 1821, a few years after the native Quapaw ceded the land to the United States. Chosen as capital based on the interest of land speculators from St. Louis, Missouri, and its central location within the state, Little Rock initially struggled to attract settlers. Arkansas’s terrain made the city difficult to reach, yet its placement on the Arkansas River gave it the advantage as a point of passage to and from the Mississippi River. A port was successfully developed, but the variable water levels of the Arkansas River still made travel challenging.

After the Civil War, the completion of the Memphis and Little Rock Railroad in 1871 connected the city to a greater network of travel, further solidifying it as the epicenter of commerce in Arkansas. In 1915, the new Arkansas State Capitol building was completed on 5th Street. With Main Street already flourishing as Little Rock’s shopping district, the intersection of Main and 5th Street, which was renamed Capitol Avenue, became the retail hub of the city given the volume of traffic to and from the capitol.

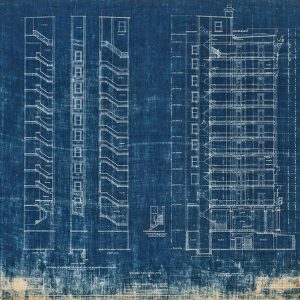

Notable structures populated the district prior to 1915. The Arkansas Carpet and Furniture Company building (1899) is the oldest structure still standing in the district. It was later remodeled and became the Pfeifer Brothers Department Store in 1912. In 1963, it became a Dillard’s Department Store when Dillard’s purchased Pfeifer’s. The Boyle Building (1909) was the city’s second skyscraper at eleven stories, later adding a twelfth story in 1949. (The 1907 Pyramid Place was the first skyscraper in the city.) Previously called the State National Bank building, its namesake went bankrupt, and the building was purchased by John F. Boyle Jr. in 1916. Besides Boyle Realty Company, the building housed a variety of retail stores, eateries, and businesses. Other buildings included the Arnold Building (1910), now known as the Atrium Building, which housed Arnold Barber Supplies, and the Galloway Building (1912), which became home to Arkansas Carpet and Furniture Company when it moved from its previous building. The Galloway Building was named after the company’s president, W. P. Galloway. In 1988, the Arkansas Repertory Theatre began performances in the Galloway building.

The distinction of having the Arkansas State Capitol down the street further encouraged development through the late 1910s and 1920s. New buildings included the Union Trust building, later known as the Sterling Building (circa 1918) after Sterling Department Store moved there; the Hall-Davidson Building (1923), another Boyle Realty Company–owned building and named after the company’s president, Walter Graham Hall; the Bracy Hardware Company Building (1923); the Back Brothers Department Store (1925), which would later house J. C. Penney and then Moses Melody Shop; and the Moore Building (1929), where the Draughon School of Business was located. The Lafayette Hotel (1925), one of Little Rock’s premier hotels, also opened during this period.

Given that the heyday of the district’s development occurred in the early 1900s, the district’s architecture is dominantly twentieth-century commercial with Art Deco, Italianate, and Sullivanesque details. The buildings represent the work of prominent Arkansas architects, including Frank Ginocchio, George Mann, Theodore Sanders, and Charles Thompson.

While the Great Depression caused development to suffer, even causing the newly built Lafayette Hotel to close for eight years, the district rebounded in the 1940s. Department stores opened new buildings or expanded in the district. The M. M. Cohn Company opened a new store in 1940, and J. C. Penney relocated to a newly built structure in 1957. Pfeifer (1954), Sterling (circa 1946), and Hall-Davidson (1946) added annexes. Hall-Davidson’s annex housed Kroger Grocery and Baking Company and later the Fabric Center. M. M. Cohn eventually expanded into the first five floors of Boyle Building in 1960.

The 1960s saw the beginning of the district’s decline, as Little Rock was expanding westward. With car ownership becoming the norm and interstates becoming plentiful nationwide, living farther from the city was no longer an inconvenience. Shopping malls outside the center of the city, such as Park Plaza built in 1959, and McCain Mall in North Little Rock (Pulaski County), were built in 1973. The construction of Interstate 630, completed in 1985, further encouraged growth westward and divided downtown. White flight in response to court-ordered school desegregation also decreased the downtown’s population.

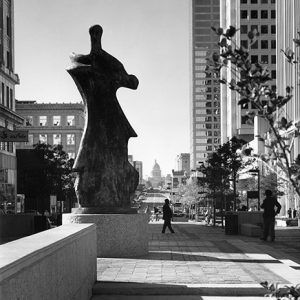

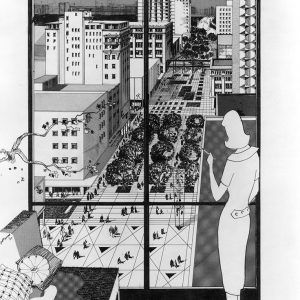

Urban renewal programs tried to combat the exodus but exacerbated the problem by demolishing hundreds of buildings, replacing them with parking lots, and displacing businesses downtown. Little Rock Unlimited Progress zoned a large portion of downtown as the Metrocentre Improvement District, which included the Capitol-Main Historic District. In an attempt to replicate the success of suburban shopping malls, the district became the centerpiece in plans to rehabilitate downtown to include a pedestrian mall. Private property owners within the Metrocentre Improvement District paid for the mall’s construction through special assessments, totaling $4.5 million. The Metrocentre Mall was completed in October 1978. It encompassed four blocks of Main Street and was closed off to traffic. Its existence was short-lived. By 1982, with flagship stores such as J. C. Penney leaving the area, people questioned the mall’s viability. As stores continued to flounder or leave, a private venture attempted to remake a downtown mall in 1987. Called the Main Street Mall, it was an enclosed structure created by integrating and remodeling five buildings, which included the J. C. Penney Building (1957), the Bracy Hardware Company Building (1923), and the Back Brothers building (1925). Smaller than the Metrocentre Mall, it occupied a half block between Capitol and 6th Street on Main. It cost $12 million to construct. This mall also failed, closing operations in 1989. Streets used for the pedestrian mall were completely opened again to vehicles in 1991.

The district today is predominately used for offices. The Arkansas Historic Preservation Program successfully nominated the district in 2012 to be included on the National Register of Historic Places. In 2013, the Capitol-Main Historic District was a featured part of the award-winning Main Street Creative Corridor project, designed by the University of Arkansas Community Design Center and architect Marlon Blackwell. Instead of focusing on restoring the district as the city’s retail heart, the project proposes a mixed-use environment with a focus on the arts. With the Arkansas Repertory Theatre already present, other creative ventures plan to join the corridor, including the Arkansas Symphony Orchestra and Ballet Arkansas. On August 8, 2023, Attorney General Tim Griffin announced that his office would be purchasing the vacant Boyle Building following its renovation.

For additional information:

“Capitol-Main Historic District.” National Register of Historic Places nomination form. On file at Arkansas Historic Preservation Program, Little Rock, Arkansas. Online at https://www.arkansasheritage.com/docs/default-source/national-registry/pu7342-pdf.pdf?sfvrsn=69c6dc47_0 (accessed November 21, 2025).

Crouch, Elisa, “Like Rip van Winkle, Downtown Waking Up.” Arkansas Democrat-Gazette, April 19, 2001, p. 1A.

“The Creative Corridor: A Main Street Revitalization,” University of Arkansas Community Design Center and Marlon Blackwell Architect, 2013. https://www.littlerock.gov/media/1995/the-creative-corridor_final-report_older_verison.pdf (accessed November 21, 2025).

Langhorne, Will. “AG Offices Moving to Boyle Building.” Arkansas Democrat-Gazette, August 9, 2023, pp. 1A, 6A. Online at https://www.arkansasonline.com/news/2023/aug/09/arkansas-attorney-general-announces-plans-to-move/ (accessed November 21, 2025).

Donald, Leroy, “Metrocentre Plans Began in ’72.” Arkansas Gazette, July 23, 1989, p. 5F.

Quapaw Quarter Association Records. Butler Center for Arkansas Studies. Central Arkansas Library System, Little Rock, Arkansas.

Roy, F. Hampton. Charles L. Thompson and Associates: Arkansas Architects, 1885–1938. Little Rock: August House, Inc., 1982.

Roy, F. Hampton, Charles Witsell Jr., and Cheryl Griffith Nichols. How We Lived: Little Rock as an American City. Little Rock: August House, 1984.

Shannon Marie Lausch

UALR Center for Arkansas History and Culture

Comments

No comments on this entry yet.