calsfoundation@cals.org

Broadside to the Sun

Broadside to the Sun is a 1946 book by Donald W. (Don) West recounting his family’s pursuit of subsistence farming in rural Washington County, Arkansas. West’s work was widely read in the northwestern Arkansas region and has become a valuable source for students of Ozarks farm ways and the impacts of twentieth-century social and economic change on the state.

Published in 1946 by W. W. Norton & Company as part of its American Lives series, Broadside to the Sun was the first book published by West, an educator who had worked at the Museum of New Mexico. West’s account was part of a trend of books celebrating rural America and the uniqueness of the Ozarks region and culture. Although clearly belonging to the “country life” genre of the 1920s–1940s, Broadside to the Sun is distinguished by the personal narrative running throughout and the careful, detailed observations of farm life taken from a farming family on the economic margins at the tail end of the Great Depression. West writes of his family’s struggles and regrets, and gives a firsthand, loving tribute to a region that was changing irrevocably even as the Wests sought to soak in the warmth of its last days. The book gained recognition in Arkansas and nationally, with newspaper reviews in the Arkansas Gazette and the New York Times. Scholars of Ozarks literature such as Miller Williams have included excerpts from Broadside of the Sun in edited collections on the region; however, the book has only appeared in one edition.

Don West and his wife Muriel Leitzell West moved their young family to a rural region of Arkansas already showing the effects of decades of depopulation. West contrasts the college-educated, artistic—and sentimental—approach to rural life of himself and his wife with the more pragmatic and brutal approaches of others seeking to make a living in the area. The book offers close observations of folklore and the lessons learned by Don and Muriel West about farming, animal husbandry, and traditional homesteading. As Don struggled to plow rocky fields and keep homes and farm buildings upright, Muriel learned about domestic chicken production and helped the family engage in local trade. Along the way, they experienced many joys of rural Ozarks life, including homemade pawpaw wine and visits with neighbors. West’s direct and often unadorned writing style and careful observations create a sympathetic narrative. Robert L. Gordon in a review for the Arkansas Gazette noted that “West is paying a debt of gratitude” to the people his family encountered.

West took the title of his book from an Ozarks vernacular phrase that describes how pasture animals such as cows and horses orient themselves, as well as how homes were also positioned, to take advantage of the sun. As Diana Sherwood, who reviewed the book upon its release for the Arkansas Historical Quarterly, noted, the phrase “broadside to the sun” also serves as West’s reflection on his and his wife’s decision to reorient their lives as subsistence farmers.

War is a growing shadow throughout Broadside’s later chapters, portending the accelerated outmigration and shift of Ozarks labor geographically toward urban centers of industrialization. West shows World War II’s effect on the livelihoods of Ozarkers and the further altering of the character of the region where he and his wife had sought refuge from the harsh modernism of Depression-era America. The book traces West’s efforts to expand the family’s enterprise by moving from the initial settlement on a small plot on relatively fertile soil near others to a larger, more isolated farm. West had gone to the larger farm at Horrigan Hollow to “work alone at a simple and colossal task,” as quoted in a 1978 Grapevine article about his life and work by Joe Neal.

The author’s brother, Harold West, created the woodcut illustrations that serve as chapter headings. Although Harold West had never ventured to the Ozarks, the illustrations are evocative of the rustic simplicity and beauty his brother sought to capture. Don and Harold West were both involved in the art scene in Santa Fe, New Mexico—also where Don met Muriel.

The narrative focus of the book is the relationship of the West family with Ribbon, a horse West acquired soon after arriving in the West Fork (Washington County) valley. Ribbon was deeply loved by the Wests and their children, and their relationship with Ribbon comes to represent the beauty and heartbreak of the Wests’ relationship with the changing landscape.

Alvis Center, a local farmer and friend of the Wests, features prominently in the book as a source of regional humor and folk wisdom. Through Center, the reader sees frustrations stemming from changing economic realities and the perceived lack of support from federal programs, even at the height of the New Deal.

Although the book did not have remarkable sales, it provided royalties enough for the Wests to return to the gentler farm at “Frogbog,” near Brentwood (Washington County), where they had first settled, and not suffer as acutely as they had on the isolated and harsh Horrigan Hollow farm. The Wests eventually left active farming for opportunities in Fayetteville (Washington County), including pursuing graduate education at the University of Arkansas, publishing additional writing, and taking part in the folklore collecting and academic study in association with folklorist Mary Celestia Parler and others.

For additional information:

“Arkansas Farmer.” New York Times, May 12, 1946, p. 22.

Gordon, Robert L. “Our Hill Country.” Arkansas Gazette, April 21, 1946, p. 12B.

Neal, Joe. “Broadside to the Sun: A Shared Dream of an Independent Life.” Grapevine, December 1, 1976.

Sherwood, Diana. “Broadside to the Sun.” Arkansas Historical Quarterly 5 (Winter 1946): 412–417.

West, Don. Broadside to the Sun. New York: W. W. Norton & Co., 1946.

Williams, Miller. “Don West: Ribbon.” In Ozark, Ozark: A Hillside Reader. Columbia: University of Missouri Press, 1981.

Joshua Cobbs Youngblood

University of Arkansas, Fayetteville

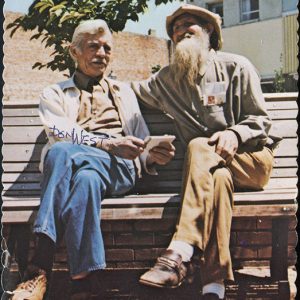

West and Henson

West and Henson  West Family

West Family  Don West

Don West

Comments

No comments on this entry yet.