calsfoundation@cals.org

Boodle Prosecutions

aka: Boodle Scandal of 1905–1908

The Boodle Scandal of 1905–1908 dealt with pervasive bribery (“boodle” is a slang term for bribe money) in the 1905 Arkansas General Assembly uncovered by Lewis Rhoton, prosecuting attorney for the Sixth Judicial District (Pulaski and Perry counties). Rhoton’s unmasking of legislators’ corruption in Arkansas in these years advanced the rise of Progressivism as a political force. When President Theodore Roosevelt visited Little Rock (Pulaski County) on October 25, 1905, he praised Rhoton’s effort to hold public officials to account. The president also decried difficulties in prosecuting the wealthy or influential, including difficulties created by the legal system itself. Problems with Arkansas’s law and judicial procedures were partly at fault for Rhoton’s lack of widespread success in proceeding against boodlers.

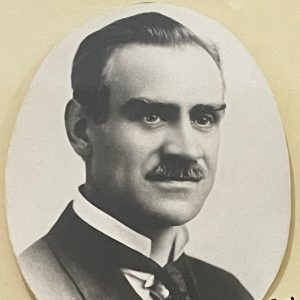

Reports of bribery by Thomas L. (Tom) Cox, a lobbyist representing most railways and insurance companies in the state, began as early as 1895. Nothing was done about it until Rhoton obtained evidence of corporate payoffs to legislators, employing undercover detectives from St. Louis whom Missouri governor Joseph W. Folk had recommended. At the same time, Rhoton exposed schemes of lawmakers themselves who extorted money from ordinary citizens before enacting laws requested by them. Estimates of the overall amount of the legislative graft ran as high as $200,000, although specific amounts found and charged against indicted officials were relatively small.

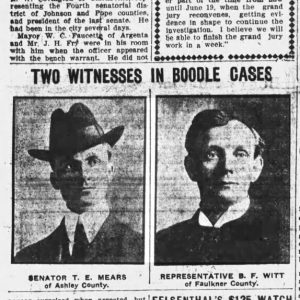

Rhoton secured grand jury indictments against sixteen state senators and representatives for bribery and perjury; one mayor and three other individuals for jury tampering or for accepting illegal railroad passes; and one public admission of guilt by a senator who was expelled in 1907 from Arkansas’s upper house. With a small staff, Rhoton struggled to bring such a high number of cases to court. Delays resulted from numerous continuances that judges granted to postpone trials. The prosecutor tried nine cases involving seven defendants. He obtained convictions in four cases against five defendants.

Lacking sufficient funding for his office to take on the extra burden of pursuing boodlers, Rhoton sued numerous corporations and won fines for their violation of Arkansas’s antitrust law, fines that he then used to pay his investigators and others working on boodler cases. These lawsuits against corporations would eventually lead to his appearance before the U.S. Supreme Court in early 1908 to win a decision for his state in the case Hammond Packing Company v. Arkansas.

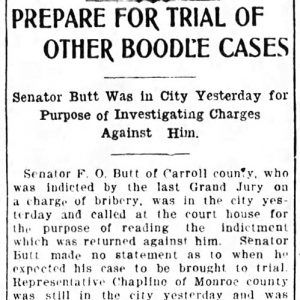

The highest-profile bribery cases arose from funding construction of the new Arkansas State Capitol building, a project of much political controversy. Without confessions, proving guilt of bribery was difficult and largely depended upon accomplices turning state’s evidence. Separate trials of two state senators accused of bribery, Alonzo Webb Covington and Festus O. Butt, produced different outcomes.

Before investigations had concluded, Rhoton mistakenly rushed the trial of Senator Covington, president of the 1905 Arkansas Senate. This mistake, combined with the senator’s strong denial of guilt, led to an acquittal verdict. A second trial for perjury resulted in a hung jury. Covington was never retried. In the first trial, Covington benefited from a much criticized ruling, based on an Arkansas law that distinguished testimony of accomplices from other witnesses, when Judge Robert Lea instructed jurors to discount admissions by Tom Cox, Marcus D. L. Cook, and George W. Caldwell that they gave Covington bribes.

In Senator Butt’s trial, Judge Edward W. Winfield did not give special instructions to the jury about accomplices; all testimony was to be judged alike for truth or falsity. Butt’s colleague Senator Reuben R. Adams confessed that he had accepted a bribe from Butt to vote for a capital funding bill. The jury found Butt guilty but declined to decide on a sentence. Winfield handed down the maximum sentence for bribery in Arkansas, two years imprisonment and a $200 fine. The Arkansas Supreme Court rejected Butt’s appeal, upholding in every respect Winfield’s rulings. The former senator, however, was released after serving only six months in the Arkansas penitentiary, as a result of a full pardon by acting governor Xenophon O. Pindall. Butt was the only corrupt legislator who served time in prison.

Arkansas’s inadequate bribery laws were, in part, revealed by minimal punishments. Penalties imposed on other legislators convicted of various kinds of bribery included a $25 fine of Representative George F. Chapline; a $10 fine of Senator Allison T. Gross; and a $100 fine and three months in the county jail for Mayor William C. Faucette of Argenta—now North Little Rock (Pulaski County)—and former mayor Frank Cumnock of Baring Cross (Pulaski County), although the Arkansas Supreme Court subsequently overturned the mayors’ convictions.

Reacting in part to public outrage over corruption, the Arkansas General Assembly in 1907 passed numerous Progressive reforms, several that had been blocked before by bribery. Assisted by Rhoton, it considered but failed to strengthen bribery laws. It also failed to enact measures to regulate lobbying, often seen at the time as the principal source of legislative corruption.

The types of bribery that Rhoton pursued included free passes issued to public officials by railroads seeking favorable treatment. Although no money exchanged hands, rail passes were extremely valuable, allowing free travel on a rail company’s routes. Both Representative Claude Fuller and Senator Ben E. McFerrin were indicted for holding free railroad passes.

Rhoton’s investigations led to a consequential political battle with U.S. senator Jeff Davis, formerly Arkansas’s three-term governor. The prosecutor secured a grand jury summons to Davis to answer questions about his use of free railroad passes when governor. Although Davis was not indicted, the senator retaliated with a political war against Rhoton when he sought a third term as prosecutor in 1908. In a variety of venues, including one face-to-face campaign showdown with the senator, Rhoton claimed that Davis had committed numerous offenses, ranging from the unethical to the criminal. Rhoton discredited Davis and won renomination. In doing so, he also indirectly helped elect as governor the Progressive businessman George W. Donaghey.

Most indicted politicians involved in the Boodle Scandal of 1905–1908 were never brought to trial. Rhoton’s resignation as prosecutor in 1908, due to illness, combined with the reluctance of lobbyist Tom Cox to testify against boodlers after a statute of limitations ended his legal jeopardy, placed cases in an indeterminate status until Judge Lea finally dismissed all charges in 1910.

Rhoton’s zealous efforts to end legislative graft through prosecutions did not survive his time in office and seemed to have had little permanent effect on the widespread corruption that marked early twentieth-century Arkansas politics. He did assist a later prosecution in 1917 to convict Senators Samuel C. Sims and Ivison C. Burgess of bribery. But reforms to deal more effectively with regulation of lobbying and to change legislative procedures to limit opportunities for misconduct would not emerge for decades.

For additional information:

Willis, James F. “Lewis Rhoton and the ‘Boodlers:’ Political Corruption and Reform During Arkansas’s Progressive Era.” Arkansas Historical Quarterly 76 (Summer 2017): 95–124.

James F. Willis

Little Rock, Arkansas

Comments

No comments on this entry yet.