calsfoundation@cals.org

Asian Longhorned Tick

aka: Bush Tick

The Asian longhorned tick (Haemaphysalis longicornis) is an ectoparasite belonging to the Phylum Arthropoda, Class Arachnida, Order Acari, and Family Ixodidae. The Asian longhorned tick is native to temperate areas of eastern and central Asia, including China, Japan, and Korea, as well as various Pacific islands, including Australia, New Zealand, Fiji, New Caledonia, western Samoa, Vanuatu, and Tonga. In August 2017, a tick from an Icelandic sheep (Ovis aries) brought to the Hunterdon County Health Department in New Jersey was identified as H. longicornis. In November 2017, a large number of H. longicornis were discovered on a sheep farm, again in Hunterdon County. This tick had also been intercepted at U.S. port cities on imported animals and materials several times and may have been present in the eastern United States for several years, but only recently detected. By 2019, the Asian longhorned tick had been found in twelve states: Arkansas, Connecticut, Delaware, Kentucky, Maryland, New Jersey, New York, North Carolina, Pennsylvania, Tennessee, Virginia, and West Virginia. Interestingly, attempts to eradicate the species from New Jersey failed; the tick successfully overwintered and became established in the state as an invasive species.

In Arkansas, the first confirmed Asian longhorned tick came from a dog (Canis latrans familiaris) in Benton County in June 2018. It was identified from a photograph and confirmed via molecular typing (polymerase chain reaction). It is not known how the tick originally made it to northwestern Arkansas, the first geographic report in a state west of the Mississippi River. In May 2022, a technician collecting ticks from the University of Arkansas System Division of Agriculture’s Savoy Research Complex in Fayetteville (Washington County) uncovered new samples of the invasive species.

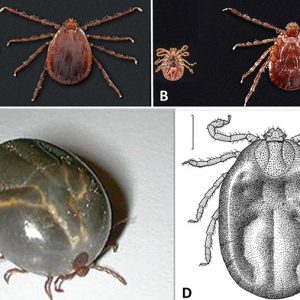

An unfed female H. longicornis is typically 2.0 to 2.6 mm (0.08 to 0.10 in.) long × 1.5 to 1.8 mm (0.06 to 0.12 in.) wide, and with engorgement, grows to 9.8 mm (0.4 in.) long × 8.2 mm (0.3 in.) wide. All life stages (larvae, nymph, adult) are uniformly dark reddish brown and lack ornamentation or distinctive marking. Unfed ticks can survive for nearly a year; depending on temperature and humidity, nymphs and adult females can survive even longer. Distinguishing a specimen taxonomically from other members of the genus Haemaphysalis requires further microscopic examination of minor physical characteristics.

This tick is a known pest of livestock, especially in New Zealand since before 1910, and can transmit bovine theileriosis to cattle (Bos taurus) but not to humans. The disease can cause considerable blood loss and, occasionally, the death of young calves. However, combatting the disease is important to dairy farmers mostly because of decreased milk production and to sheep farmers because of reduced wool quantity and quality.

Unfortunately, the tick is a vector of, and has been associated with several other, tickborne diseases in humans, including Lyme spirochetes, spotted fever group rickettsiae (Ehrlichia chaffeensis and Anaplasma bovis), Russian spring-summer encephalitis, Powassan virus, Khasan virus, tick-borne encephalitis virus, Japanese spotted fever, and severe fever with thrombocytopenia syndrome. However, pathogens in humans have so far not been detected in the species in the United States.

In addition to livestock, H. longicornis infests hosts like other mammals and birds. In addition to sheep, it multiplies quickly in other farm animals such as chickens, horses, and swine. Natural infestations have been found on wild fauna such as marsupials, bears, foxes, deer, hares, rats, and birds. Even ferrets have been found to harbor infestations, and it has also been known to occur on domestic cats, domestic dogs, and humans. It is thought to migrate by parasitizing birds, which distribute it to new geographic regions.

The reproduction of Asian longhorned ticks is unusual among tick species. The tick can reproduce sexually or by asexual means (parthenogenesis). The latter seems to be prevalent in northern Japan and Russia, whereas the former is seen in southern Japan, southern Korea and southern parts of Russia. An aneuploid taxon with additional chromosomes capable of both sexual and parthenogenetic capability is found in China. According to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, a single female tick can produce up to 2,500 eggs at oviposition, even without mating. Larvae emerge from eggs laid in the soil in late summer or early fall and have three active developmental stages—six-legged larvae, eight-legged nymphs, and eight-legged adults—all feeding exclusively on vertebrate blood. This tick is capable of moving on and off hosts three times, as the blood meal is a necessary preamble to molting to the next stage and eventually for egg development. The larvae crawl onto grass to quest and attach to passing hosts, feeding on their blood for three to five days. Subsequently, they fall off the host onto the ground, where they molt to become a nymph and become inactive during the winter. In the following spring, the nymphs become active again, locate a new host, and attach and feed for five to seven days, then drop off and molt to relatively small adults. Adults attach to a host, feed for one to two weeks by which time they are about 10 mm in size, then drop off and digest the blood as they develop eggs. To complete the life cycle, females lay eggs and die.

For additional information:

Beard, C. Ben, James Occi, Denise L. Bonilla, Andrea M. Egizi, Dina M. Fonseca, James W. Mertins, Bryon P. Backenson, Waheed I. Bajwa, Alexis M. Barbarin, Matthew A. Bertone, and Justin Brown. “Multistate Infestation with the Exotic Disease–Vector Tick Haemaphysalis longicornis—United States, August 2017–September 2018.” Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report 67 (2018): 1310–1313.

Heath, A. C. G. “Biology, Ecology and Distribution of the Tick, Haemaphysalis longicornis Neumann (Acari: Ixodidae) in New Zealand.” New Zealand Veterinary Journal 64 (2016): 10‒20.

Heath, A. C., James L. Occi, R. G. Robbins, and Andrea Egizi. “Checklist of New Zealand Ticks (Acari: Ixodidae, Argasidae).” Zootaxa 2995 (2011): 55‒63.

Hoogstraal Harry, F. H. S. Roberts, G. M. Kohls, and V. J. Tipton. “Review of Haemaphysalis (Kaiseriana) longicornis Neumann (Resurrected) of Australia, New Zealand, New Caledonia, Fiji, Japan, Korea, and Northeastern China and USSR and its Parthenogenetic and Bisexual Populations (Ixodoidea: Ixodidae).” Journal of Parasitology 54 (1968): 1197‒1213.

Lee, Mi-Jin, and Chae Joon-Seok. “Molecular Detection of Ehrlichia chaffeensis and Anaplasma bovis in the Salivary Glands from Haemaphysalis longicornis Ticks.” Vector-Borne and Zoonotic Diseases 10 (2010): 411–413.

Meng Z., L. P. Jiang, Q. Y. Lu, S. Y. Cheng, J. L. Ye, and L. Zhan. “Detection of Co-Infection with Lyme Spirochetes and Spotted Fever Group Rickettsiae in a Group of Haemaphysalis longicornis.” Zhonghua Liu Xing Bing Xue Za Zhi (in Chinese) 29 (2008): 1217–1220.

McAllister, Chris T., Lance A. Durden, and Henry W. Robison. “The Ticks (Arachnida: Acari: Ixodida) of Arkansas.” Journal of the Arkansas Academy of Science 70 (2016): 141–154. Online at https://scholarworks.uark.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=2195&context=jaas (accessed October 26, 2020).

National Haemaphysalis longicornis (Asian Longhorned Tick) Situation Report. Online at https://www.aphis.usda.gov/animal_health/animal_diseases/tick/downloads/longhorned-tick-sitrep.pdf (accessed October 26, 2020).

Oliver, James H. Jr., K. Tanaka, and M. Sawada. “Cytogenetics of Ticks (Acari: Ixodoidea). 12. Chromosome and Hybridization Studies of Bisexual and Parthenogenetic Haemaphysalis longicornis Races from Japan and Korea.” Chromosoma 42 (1973): 269‒288.

Rainey, T, J. L. Occi, R. G. Robbins, and E. Andrea. “Discovery of Haemaphysalis longicornis (Ixodida: Ixodidae) Parasitizing a Sheep in New Jersey, United States.” Journal of Medical Entomology 55 (2018): 757‒759.

Tufts, D. M., M. C. Van Acker, M. P. Fernandez, A. DeNicola, A. Egizi, and M. A. Diuk-Wasser. “Distribution, Host Seeking Phenology, and Host and Habitat Associations of Haemaphysalis longicornis Ticks, Staten Island, New York, USA.” Emerging Infectious Diseases 25 (2019): 792‒796.

Chris T. McAllister

Eastern Oklahoma State College

Science and Technology

Science and Technology Asian Longhorned Tick

Asian Longhorned Tick

I was diagnosed with a tickborne illness after picking a tick just like that off of me in mid-to-late 2019. By the time I went in to the doctor, I was so sick and weak I had to be carried in. Lifting my head was near impossible. I was then given antibiotics that I had a severe and unprecedented reaction to. I was nearly dead–from a tick bite! So stop saying “oh it’s JUST a tick; this is Arkansas.” My dog diagnosed with same as me died from it. I’ve actually tested positive twice for it, in 2019 and 2022. Please protect yourselves.