calsfoundation@cals.org

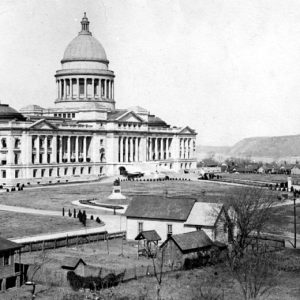

Arkansas State Capitol Building

The Arkansas Capitol building is the seat of the state’s government, housing its legislature as well as the staffs of six out of Arkansas’s seven constitutional officers. The monumental neo-classical structure gave rise to political controversy during its construction but has generally been praised since its completion in 1915.

The current building is the second capitol built in Little Rock (Pulaski County). It replaced the State House (today’s Old State House Museum) erected in the 1830s between Markham Street and the banks of the Arkansas River in downtown Little Rock. During the 1890s, calls were raised for a new capitol, but sentiment and financial considerations, coupled with the lack of a suitable site, effectively blocked the project.

By 1899, the state’s financial condition had improved while conditions within the State House worsened. In early January, after heavy rains, large pieces of ceiling plaster fell in the Senate chamber. On January 12, 1899, Senate Concurrent Resolution 3 was introduced, calling for the construction of a new seat of government. Governor Daniel Webster Jones lent his support to the bill. He suggested that the new capitol be built on the site of the Arkansas State Penitentiary on 5th Street, describing the property as “too valuable” to be used as a prison. After a month of deliberation, the House adopted the resolution, and Jones signed it into law on February 13, 1899. Later that year, the passage of Act 128 allocated $50,000 to hire an architect and begin the project. It also stipulated a total cost for the envisioned capitol not to exceed one million dollars. The capitol would be built, as Governor Jones had suggested, on the penitentiary site, and the act made 200 state convicts available to work on the capitol project as a means of saving money. The law also created an appointive commission to oversee the construction.

In May 1899, the Capitol Commissioners hired St. Louis architect George Mann, who produced plans for a building that could be built, he estimated, under the million-dollar limit. Mann’s design would accommodate the state’s legislature, its statewide elected officials, and the Arkansas Supreme Court, plus assorted executive-branch offices, departments, and commissions. Convict crews supervised by experienced builder and Capitol Commissioner George Donaghey began work in July 1899. Despite some delays, the foundation was essentially complete by late October 1900, and the cornerstone was laid on November 27, 1900.

Construction slowed after this promising beginning. The capitol was to be a “pay-as-you-go” project, and the legislature was reluctant to vote enough funds to keep the project going. The capitol remained controversial, in part because of opposition from former attorney general and current governor (and ex-officio Capitol Commissioner) Jeff Davis. Davis originally justified his stand on grounds of economy and the supposed illegality of building a capitol anywhere but on the grounds occupied by the State House; as the project wore on, his complaints included malfeasance on the part of the contractors and architect. Davis enjoyed wide support across the state, and his faction within the state legislature did much to slow capitol construction appropriations. The choice of materials likewise slowed work: the hard native limestone (“Arkansas marble”) selected for the capitol’s exterior wore out quarry equipment prematurely, and the quarry’s owners were accused of filling lucrative private orders before attending to their capitol contracts.

In 1905, concerns raised over alleged shortcuts in construction seemed to support Davis’s criticisms. Four state senators and two representatives were indicted that summer for accepting bribes in connection with capitol construction appropriations (part of what was called the Boodle Scandal). Ultimately only Senator Festus Butt was convicted of accepting money from contractor Caldwell & Drake, but the scandal tainted public and political attitudes toward the project. In the summer of 1906, new allegations of shoddy workmanship and substandard materials were leveled against Caldwell & Drake. Construction slowed to a standstill by mid-1907; the uncompleted capitol was predicted to become “the habitat of owls and bats.”

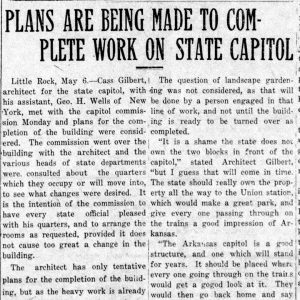

In 1908, the project became the focus of the Arkansas gubernatorial race. Former Capitol Commissioner George Donaghey was elected with a comfortable majority and took office in 1909 ready to rekindle the work. With his support, the Capitol Commissioners dismissed Caldwell & Drake and took possession of the uncompleted building in the name of the state. The commission offered New York-based architect Cass Gilbert the task of restoring and completing the capitol. Gilbert was a likely choice for the task: his portfolio included the recently-completed Minnesota Capitol and the in-progress Woolworth Building in downtown New York. Moreover, he enjoyed a reputation for bringing projects to timely completion. Gilbert accepted the job on June 27, and work tearing out defective construction soon began.

This bold action prompted a flurry of injunctions, lawsuits, and counter suits, but while arguments flew in court, work on the building accelerated. By February 1910, the capitol’s inadequate iron and steel work was replaced, fireproofing was improved, and new reinforced concrete floors were poured. Mann’s original metal dome design was scrapped in favor of a stone dome closely resembling that of the Mississippi State Capitol (unbeknownst to Gilbert, this feature had been designed by George Mann). Plans for exterior statuary were also scrapped, saving money while simplifying the building’s neo-classical silhouette. By December 1910, the building was unfinished but deemed by Donaghey and the commission ready for occupation. On January 8, 1911, over the protests of the secretary of state, wagons brought their first loads of furniture and files from the State House to the new capitol. The General Assembly met there on January 9. The state’s executives followed suit, and the state Supreme Court finally moved to their new facility in 1912.

When the assembly met in January 1911 in the new building, many details remained unfinished. It lacked permanent arrangements for heating and light, and much of the interior was finished in tile and plaster. In spite of Donaghey’s best efforts, the legislature failed to authorize adequate appropriations for the project. Work continued, although at a slower pace. In 1912, Donaghey was defeated in his bid for a third term by Joseph T. Robinson, who replaced Donaghey on the Capitol Commission. Ironically, one of Robinson’s campaign themes was that Donaghey had not fully lived up to his 1908 promise to complete the capitol. Robinson, however, resigned the governorship in order to enter the U.S. Senate in early 1913; his successor, George W. Hays, reappointed Donaghey to the commission. Additionally, the legislature of 1913 appropriated more than $500,000 to pay already-incurred construction costs and to finish the capitol.

With money on hand, Gilbert was able substantially to revise and complete the capitol’s interior. Features designed to meet a low budget were now built to a new, high standard. Eight offices were added to the ground floor. Marble replaced lesser materials throughout the building. Landscaping was begun, and an outside heating plant was equipped. By January 1, 1915, the capitol building was deemed essentially complete. Donaghey estimated the final cost of the project at slightly more than $2.2 million.

Today, the Arkansas State Capitol looks much as it did in 1915. Its neo-classical revival design combines elements of Doric, Ionic, and Corinthian styles. Like most American statehouses, the Arkansas Capitol’s layout is that of a cross, elongated along its north-south axis, surmounted by a prominent dome. The capitol measures 440 feet along its north-south axis, and just over 195 feet from east to west. Above the exterior walls of Arkansas limestone rises the slightly conical dome built of softer Indiana limestone; 213 feet separate ground level from the top of the gilded lantern cupola. Inside, the building contains nearly 287,000 square feet of space, no longer sufficient to hold the majority of state offices and departments. A complex of office buildings around the capitol reflects the twentieth-century growth of Arkansas’s bureaucracy.

In 1958, the state Supreme Court relocated to the nearby Justice Building, and today, the attorney general’s office is located in downtown Little Rock. The legislature and six of Arkansas’s constitutional officers, however, remain firmly based in the capitol. Year around, about 350 men and women work in the capitol’s office spaces; this number swells in January of each odd-numbered year when the Arkansas General Assembly convenes for its mandated session. A cafeteria (which did not desegregate until 1965), snack bar, shoe shine stand, and hair salon serve legislators, civil servants, and the public alike. Recent restorations have returned the Old Supreme Court Chamber, the Governor’s Reception Room, the Senate Chamber, and the rotunda to nearly their original appearance while preserving their utility. Cass Gilbert’s suggestions for historical murals to cover the interior walls were never carried out; four murals by Fayetteville (Washington County) artist Paul Heerwagen, installed above the grand staircases leading to Senate and House chambers, remain the only public art commissioned for the building. Decades of revisions and replanting have altered the appearance of the capitol’s grounds, but recent projects have restored elements of the original grounds plan developed by landscape architect Frank Blaisdell. These include lighting pylons flanking the capitol’s east-side promenade and ornamental walkways around the monuments to Confederate veterans and Confederate women located northeast and southeast, respectively, of the capitol. The capitol building was listed on the National Register of Historic Places on June 28, 1974.

In August 2023, a proposal was approved to build an underground walkway to connect the capitol building with the “Big MAC” (multi-agency complex) building that is about sixty yards away. The cost for the multi-year project was estimated at $3.87 million. The construction was coupled with major planned improvements to the HVAC system on the north side of the capitol. The underground walkway opened to the public on January 13, 2025, having cost $3.86 million.

For additional information:

“Arkansas State Capitol.” National Register of Historic Places nomination form. On file at Arkansas Historic Preservation Program, Little Rock, Arkansas. Online at https://www.arkansasheritage.com/arkansas-historic-preservation-program (accessed January 10, 2023).

Capitol Construction Archives. Secretary of State’s Office, Little Rock, Arkansas.

Donaghey, George. Building A State Capitol. Little Rock: Parke-Harper Company, 1937.

Goodsell, Charles. The American Statehouse: Interpreting Democracy’s Temples. Lawrence: University Press of Kansas, 2001.

Irish, Sharon. Cass Gilbert, Architect. New York: Monacelli Press, 1999.

Ledbetter, Calvin. Carpenter from Conway: George Washington Donaghey as Governor of Arkansas, 1909–1913. Fayetteville: University of Arkansas Press, 1993.

Mann, George R. “Appendix: George R. Mann’s Comments on George W. Donaghey’s Building a State Capitol.” Arkansas Historical Quarterly 31 (Summer 1972): 134–149.

Smith, Hubert. A Century of Pride: The Arkansas State Capitol. Little Rock: Arkansas State Capitol Association, 1983.

Treon, John A. “Politics and Concrete: The Building of the Arkansas State Capitol, 1899–1917.” Arkansas Historical Quarterly 31 (Summer 1972): 99–134.

David Ware

Arkansas Secretary of State’s Office

Arkansas Bar Association Veterans Memorial

Arkansas Bar Association Veterans Memorial  Arkansas State Capitol Building

Arkansas State Capitol Building  Arkansas State Capitol Repairs

Arkansas State Capitol Repairs  Arkansas State Capitol

Arkansas State Capitol  Arkansas State Capitol Building

Arkansas State Capitol Building  Capitol Balcony

Capitol Balcony  Capitol Construction

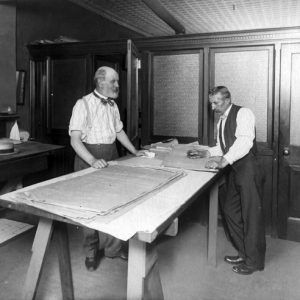

Capitol Construction  Capitol Construction

Capitol Construction  Capitol Construction

Capitol Construction  Capitol Interior

Capitol Interior  Desegregation of Central High School Protest Rally

Desegregation of Central High School Protest Rally  Dome and Chandelier

Dome and Chandelier  George Donaghey

George Donaghey  Faubus Bust

Faubus Bust  Firefighters Memorial

Firefighters Memorial  Education, Mural by Paul Heerwagen

Education, Mural by Paul Heerwagen  Religion, Mural by Paul Heerwagen

Religion, Mural by Paul Heerwagen  War, Mural by Paul Heerwagen

War, Mural by Paul Heerwagen  Justice, Mural by Paul Heerwagen

Justice, Mural by Paul Heerwagen  House Chamber

House Chamber  Little Rock Nine Monument

Little Rock Nine Monument  George Mann

George Mann  Monument to Confederate Women

Monument to Confederate Women  Monument to Confederate Women

Monument to Confederate Women  Skylight

Skylight  Staircase to Senate Chamber

Staircase to Senate Chamber  State Capitol Building

State Capitol Building  State Capitol Plans

State Capitol Plans  Vietnam Veterans Memorial

Vietnam Veterans Memorial  Vietnam Veterans Memorial

Vietnam Veterans Memorial  War of 1812 Monument

War of 1812 Monument  Women's March for Arkansas, 2017

Women's March for Arkansas, 2017

Comments

No comments on this entry yet.