calsfoundation@cals.org

Arkansas Signatories of the Southern Manifesto

Written by several Southern senators and members of the U.S. House of Representatives, the “Declaration of Constitutional Principles” served as a response to the U.S. Supreme Court’s 1954 decision in Brown v. Board of Education of Topeka, Kansas, leading to the ostensible end of legal segregation in public schools across the country. Popularly known as the Southern Manifesto, the 1956 document was signed by members of Congress from eleven states, including both senators and all six representatives from Arkansas.

Opposition to the Brown decision was immediate across the South, but organized resistance was slow to emerge. Three school districts in Arkansas—Charleston (Franklin County), Fayetteville (Washington County), and Hoxie (Lawrence County)—desegregated immediately following the decision, and the Little Rock School Board announced a plan to follow suit with the start of the 1957–58 academic year. The goal of the authors of the document was to encourage resistance to integration efforts and support the idea that the end of segregation was not inevitable regardless of the Supreme Court decision.

Numerous senators participated in the drafting of the document, with the first three drafts written by Strom Thurmond of South Carolina and Harry Byrd of Virginia. These drafts included references to interposition, a theory that individual states could oppose federal actions if the state deemed those actions to be unconstitutional. In light of the inclusion of interposition and a statement from Thurmond and Byrd that they would issue the statement regardless of whether other Congress members signed on, many more moderate members became involved with the document.

This led to a meeting of most of the Southern members, who agreed that a less extreme statement signed by a majority of their group would make a deeper impact. A new committee consisting of Senators Richard Russell of Georgia, Sam Ervin Jr. of North Carolina, and John B. Stennis of Mississippi worked on two more drafts. Members of the Southern delegation still felt that the wording in the document was too strong, as it supported interposition. The sixth and final draft was written by Thurmond, Russell, Stennis, Price Daniel of Texas, and J. William Fulbright of Arkansas.

This draft did not include support for interposition and specifically called for Southerners not to break the law in defiance of the Brown decision. This softer language secured the signatures of a majority of Southern members of Congress. A total of seventy-seven members of the House signed the document, representing the states of Alabama, Arkansas, Florida, Georgia, Louisiana, Mississippi, North Carolina, South Carolina, Tennessee, Texas, and Virginia. The entire House delegations of Alabama, Arkansas, Georgia, Louisiana, Mississippi, South Carolina, and Virginia signed. Both senators signed from the following states: Alabama, Arkansas, Florida, Georgia, Louisiana, Mississippi, North Carolina, South Carolina, and Virginia. Neither Tennessee senator signed, nor did Lyndon B. Johnson of Texas.

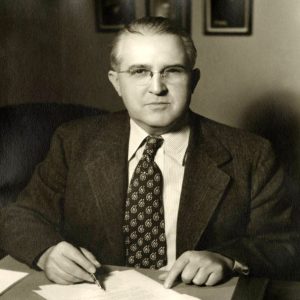

The conservative members of the Arkansas delegation eagerly signed the proclamation. Ezekiel “Took” Gathings, representing the First District; William Norrell of the Sixth District; and Wilbur D. Mills of the Second District all agreed to sign after being approached by Oren Harris, the member representing the Fourth District. Mills later recounted that he felt forced to sign the document and would lose his seat if he refused. Senator John McClellan also agreed to sign with little prompting.

J. William Fulbright worked on the final draft of the manifesto and reportedly helped reduce the fiery vitriol contained in early editions. Members of his staff prepared a press release detailing his opposition to the manifesto, but he ultimately signed the document.

Fulbright’s signature was the most surprising of the entire Arkansas delegation. Later in his career, he voted in 1967 to confirm Thurgood Marshall as the first African American associate justice on the United States Supreme Court and voted to reauthorize the Voting Rights Act in 1970.

James Trimble of the Third District and Brooks Hays of the Fifth District were the last two members of the Arkansas delegation to agree to sign. Trimble was in the Bethesda Naval Hospital when Governor Orval Faubus arrived with Hays and Oren Harris. The men discussed the document for hours before Trimble and Hays agreed to sign. Hays publicly renounced his signature later in life but initially justified signing the document.

The manifesto was officially read into the Congressional Record on March 12, 1956, by Senator Walter George of Georgia. Hays faced some pushback from the African American community in the state after his signature appeared on the document. A group of African American ministers met with Hays as he prepared for the Democratic Party primary, and he asked for their forgiveness. Most, if not all, gave him their blessing.

None of the Arkansas signatories lost their seats following the publishing of the manifesto, although Hays would lose to write-in candidate Dale Alford in 1958, following the Central High Desegregation Crisis. The ultimate outcome of the publication of the manifesto was to create further division on the topic of integration in Arkansas and across the South while giving white supremacists hope that they could overturn the Brown decision.

For additional information:

Aucoin, Brent. “The Southern Manifesto and Southern Opposition to Desegregation.” Arkansas Historical Quarterly 55 (Summer 1996): 173–193.

Badger, Tony. “‘The Forerunner of Our Opposition’: Arkansas and the Southern Manifesto of 1956.” Arkansas Historical Quarterly 56, no. 3 (1997): 353–360.

———. “Southerners Who Refused to Sign the Southern Manifesto.” Historical Journal 42 (June 1999): 517–534.

Day, John Kyle. “The Fall of a Southern Moderate: Congressman Brooks Hays and the Election of 1958.” Arkansas Historical Quarterly 59 (Autumn 2000): 241–64.

———. The Southern Manifesto: Massive Resistance and the Fight to Preserve Segregation. Jackson: University Press of Mississippi, 2014.

“The Decision of the Supreme Court in the School Cases—Declaration of Constitutional Principles.” Congressional Record, 84th Congress Second Session. Vol. 102, part 4 (March 12, 1956). Washington DC: Governmental Printing Office, 1956, pp. 4459–4460.

David Sesser

Southeastern Louisiana University

Comments

No comments on this entry yet.