calsfoundation@cals.org

Arkansas Constitutions

aka: Constitutions of Arkansas

State constitutions serve as the foundation for statutory laws, rules and regulations, and government for a state. These documents also serve as historic and cultural indicators of significant events and impacts. In 1836, the state constitutional convention drafted a document to qualify Arkansas for statehood; this first constitution was brief, flexible, general in language, and relatively lenient in terms of power. In 1861, the state needed a new constitution as it left the Union. Very few other substantive changes were made. In 1864, a third constitution was needed to bring Arkansas back into the Union. In 1868, the state adopted its constitution, which endured throughout the Reconstruction Era, with Arkansas being basically an administrative unit of the national government, overseen by federal officials. Then, finally, the current constitution in 1874 was written at the end of Reconstruction and was drafted to protect the people of the state from the government by limiting its powers. In the numerous attempts to revise or update the document in more than a century since, those issues have been discussed both in the proceedings of the conventions and in the campaigns on the proposed documents, all of which have been defeated.

The Road to Statehood

In 1833, Ambrose Sevier, a delegate to Congress from the Arkansas Territory, submitted a bill providing for a census throughout his territory to determine if there were enough people for the territory to qualify for statehood. Many in Congress were reluctant to admit another slave state because the Missouri Compromise had left the slave and non-slave states with equal numbers of senators. However, many in Arkansas Territory grew impatient and elected delegates to a state constitutional convention before Congress agreed for the territory to do so. The plantation and slave owners of east Arkansas led the movement and dominated the convention. Territorial Governor William Fulton refused to sign the legislative act authorizing the convention. The U.S. attorney general, Benjamin F. Butler, however, ruled that the people had a democratic right to assemble, gather, petition the government, and express their opinions on what a potential state constitution should contain.

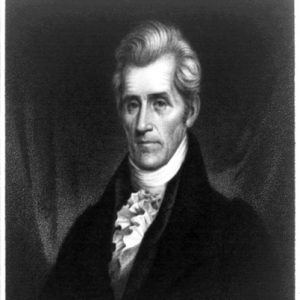

Arkansas’s first state constitution was ratified by the United State Congress on January 30, 1836. Sponsors of the legislation in the U.S. Congress were Senator John C. Calhoun of South Carolina, Senator Thomas Hart Benton of Missouri, Senator Henry Clay of Kentucky, and Senator James Buchanan of Pennsylvania. On June 15, President Andrew Jackson signed the congressional act making Arkansas Territory a state.

The First Arkansas Constitution (1836)

The first constitution was brief, flexible, and more closely modeled after the U.S. Constitution than later Arkansas constitutions were. For example, no salaries were set in the constitution, as later would be the case. Slavery was recognized, and emancipation required the consent of the owner. The governor, legislators, and county officials were elected by the people, while the secretary of state, auditor, treasurer, supreme and circuit court judges, and prosecuting attorneys were selected by joint legislative session. Governors, who would serve four-year terms, had to be at least thirty years of age and state residents for ten years. The constitution allowed all free adult white males to vote with no property or literacy restrictions, and the General Assembly was apportioned according to the free white male population.

The Second Arkansas Constitution (1861)

The first constitution remained in effect until Arkansas seceded from the Union on May 6, 1861. The new constitution was generally the same as the original, except for references to the Confederate States of America replacing references to the United States of America, a legal prerequisite to joining the Confederacy. The second constitution was ratified by the Secession Convention, chaired by David Walker of Fayetteville (Washington County), who had not favored secession.

The Third Arkansas Constitution (1864)

Arkansas’s third constitution was written under the terms of Abraham Lincoln’s plan for wartime reconstruction, which aimed to hasten the reestablishment of loyal state governments in the South. Federal recognition and financial support would come once only ten percent of those who had voted in the state in 1860 took an oath of allegiance to the Union. Adopted on January 19, 1864, and ratified on March 14, 1864, in an election supervised by Federal soldiers, it provided for a Unionist state government even while a Confederate one, now exiled to Washington (Hempstead County), continued to exist.

The 1864 constitution abolished slavery and repudiated secession but did not define the rights former slaves would enjoy. Also, this constitution, unlike that of 1836, provided for the popular election of secretary of state, auditor, treasurer, and judges. It also created the office of lieutenant governor.

The Fourth Arkansas Constitution (1868)

Arkansas reentered the Union in 1868. The Reconstruction legislature ratified the new constitution on March 13, 1868, to begin the Reconstruction Era. Among other provisions, this constitution declared racial discrimination illegal, undertook to provide support for public education and for a university, and fixed legislative apportionments to favor counties with large African-American populations. This constitution was written under the terms of the Reconstruction Acts of 1867, by which Congress required former Confederate states to create new constitutions that allowed adult African-American males to vote. This constitution also greatly enhanced the power of the state government, especially the governor. Four-year terms were restored, and the governor was given broad power to appoint officials, including judges. This was necessary because the loyalty of many former Confederates was in question, so few of them were allowed to vote.

The Fifth (and Current) Arkansas Constitution (1874)

After Reconstruction, Arkansas adopted its current constitution in 1874 as a reaction against the centralized authority of the Reconstruction period. A Democratic majority replaced the Reconstruction legislature, which had been mostly Republican. A new state constitutional convention was called in 1874. It worked during most of the summer in a generally harmonious process. For the first time since the Civil War, the Democrats outnumbered the Republicans but remained civil, courteous, and did not take some of the provisions as far as they could have. On October 13, 1874, the constitution was approved by the people in a special election by a three-to-one majority. Democrats swept the offices of governor, secretary of state, state treasurer, state auditor, and attorney general, in addition to swelling their ranks in the General Assembly.

Arkansans were generally distrustful of government after seeing such tempestuous times—from nominal military rule, to three years of civil war, to four years of civil government loyal to the United States, to a military regime under Federal generals, and finally political reconstruction, six years of Republican rule, and Democratic upheaval. Therefore, the 1874 constitution reflects a general suspicion of government and authority. The document incorporated more changes than any of the other constitutions in the state’s history, and most of these revisions were highly rural, restrictive, and negative in nature. County governments became all powerful as administrative units of the state, with jurisdiction over roads and bridges, local judiciary, and taxation as well as spending. The state’s powers to tax and borrow were severely limited, the terms of elected officials were reduced from four years to two years, the number of county officials was increased from two to ten, and the legislative sessions were limited to sixty days every two years. The governor’s power was greatly reduced, so he could appoint far fewer officials. At the same time, vetoes could be overridden by a simple majority. Detailed provisions ensured that governmental power would not be misused, and a great deal of authority transferred from state to local government.

Failed Constitutional Conventions

Several major attempts were made to replace the current document with a new constitution—in 1918, 1970, and 1980. The first convention after 1874 was during World War I in 1918, the sixth state constitutional convention. The proposed document included women’s suffrage, statewide prohibition, the creation of the lieutenant governor’s office, but it did not propose any changes in taxation or financing. The defeat came amid the war and a worldwide flu pandemic. In 1969–70, the seventh state constitutional convention met during the so-called “Young Turks” movement and the tenure of reform-oriented Governor Winthrop Rockefeller. A very progressive document was offered to the voters, but the campaign was dominated with discussions of taxation and government power, and voters rejected the document. In 1979–80, the eighth state convention worked hard on a new document that finally mirrored much of the convention of the previous decade, with an effort to steer the campaign debate, but the result was the same—rejection of the new document. The power to tax was central to each of the campaign debates on the new documents, and in each case, the providing of new flexibility and authority to state government and officials were the foundation of voter decision making. Each time, the voters narrowly rejected change.

During the years since the current constitution’s adoption, more than 100 amendments have been adopted, covering issues and entities such as salary limits, tax limits, public finance, term limits, abortion, judicial process, paternity, states’ rights, gambling, voter registration, interest rates, county government reorganization, the Game and Fish Commission, the Highway Commission, workers’ compensation, filling vacancies (including board and commission appointments, as well as filling offices when incumbents, for any reason, can no longer continue in office), hospitals, industrial development, and education. A state government’s needs change over time, and Arkansans have responded by loading an antiquated constitution down with amendments rather than creating a more modern document.

For additional information:

Arkansas Constitutions. Arkansas Digital Archives, Arkansas State Archives. https://digitalheritage.arkansas.gov/constitutions/ (accessed June 21, 2022).

“Arkansas Law Section.” Arkansas State Legislature. https://www.arkleg.state.ar.us/ArkansasLaw (accessed October 20, 2022).

Cahill, Bernadette. “A Bulwark against Equality: The 1868 Constitutional Convention in Little Rock, Arkansas.” Pulaski County Historical Review 67 (Fall 2019): 84–89.

Cash, Marie. “Arkansas Achieves Statehood.” Arkansas Historical Quarterly 2 (December 1943): 292.

Goss, Kay C. The Arkansas State Constitution: A Reference Guide. Westport, CT: Greenwood Press, 1993.

Harris, Rodney W. “Arkansas’s Divided Democracy: The Making of the Constitution of 1874.” Phd diss., University of Arkansas, 2017. Online at https://scholarworks.uark.edu/etd/2446/ (accessed July 6, 2022).

Ledbetter, Cal, Jr. “The Constitution of 1836: A New Perspective.” Arkansas Historical Quarterly 41 (Autumn 1982): 215–252.

———. “The Constitution of 1868: Conqueror’s Constitution or Constitutional Continuity?” Arkansas Historical Quarterly 44 (Spring 1985): 16–41.

Ledbetter, Calvin R., Jr. “The Constitutional Convention of 1917–1918.” Arkansas Historical Quarterly 24 (Spring 1975): 3–40.

———. “The Proposed Arkansas Constitution of 1980.” Arkansas Historical Quarterly 60 (Spring 2001): 53–74.

Nunn, Walter. “The Constitutional Convention of 1874.” Arkansas Historical Quarterly 27 (Autumn 1968): 177–204.

Kay C. Goss

Electronic Data Systems Corporation

1970 Constitution Campaign

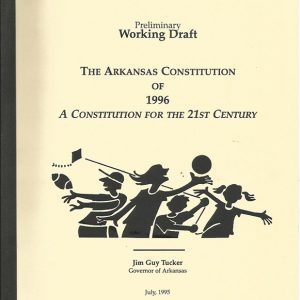

1970 Constitution Campaign  1996 Constitution

1996 Constitution  Arkansas Constitution of 1874

Arkansas Constitution of 1874  Thomas Hart Benton

Thomas Hart Benton  John Calhoun

John Calhoun  William Fulton

William Fulton  President Andrew Jackson

President Andrew Jackson  Grandison Royston

Grandison Royston  Ambrose Sevier

Ambrose Sevier  David Walker

David Walker

Comments

No comments on this entry yet.