calsfoundation@cals.org

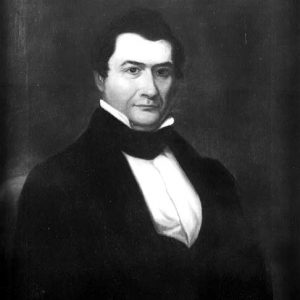

Ambrose Hundley Sevier (1801–1848)

Ambrose Hundley Sevier was a territorial delegate and one of the first U.S. senators from the state of Arkansas. Sevier was also one of the founders of a political dynasty which ruled antebellum Arkansas politics from the 1820s until the Civil War. His cousin Henry Wharton Conway founded the Arkansas Democratic Party, and his other cousin, James Sevier Conway, served as Arkansas’s first state governor, while yet another cousin, Elias Nelson Conway, was the state’s fifth chief executive. He also married into the powerful Johnson family, and his brother-in-law Robert W. Johnson rose to prominence in antebellum Arkansas politics.

Born on November 10, 1801, in Greene County, Tennessee, to John Sevier and Susannah Conway, he was the grandnephew of John Sevier, a Revolutionary War hero and the first governor of Tennessee. Sevier left Tennessee in 1820, settling first in Missouri and then, finally, in Little Rock (Pulaski County) by 1821. That October, Arkansas’s second territorial legislature convened for the first time in Little Rock, and Sevier became clerk for the territorial House of Representatives. Two years later, he was admitted to the bar and won a seat in the territorial lower house representing Pulaski County. In 1827, his fellow legislators elected him as speaker of the Arkansas Territorial House of Representatives.

On September 27, 1827, Sevier married Juliette E. Johnson, the eldest daughter of Territorial Superior Court Judge Benjamin Johnson. With this marriage, Sevier entered another powerful political family. Judge Johnson’s older brother, Richard Mentor Johnson, served in both houses of the U.S. Congress from Kentucky and eventually became the vice president of the United States under President Martin Van Buren. Juliette Johnson’s, brother Robert Ward Johnson, represented Arkansas in both houses of the U.S. Congress and in the Confederate Congress. Sevier and his wife had four children: Annie M., Mattie J., Elizabeth, and Ambrose H Sevier Jr. Related by blood to the Conways and by marriage to the Johnsons, Sevier now became a central figure in “The Family,” a dynasty which dominated Arkansas throughout the antebellum era, with members of these families and their relations holding office for an aggregate number of 190 years.

Sevier assumed leadership of the family after his cousin, Territorial Delegate Henry W. Conway, was killed in a duel in 1827. In December, 1827, Sevier was elected territorial delegate in a special election, taking his seat in Congress on February 13, 1828. He quickly aligned himself with the Andrew Jackson, and his political faction evolved into Arkansas’s Democratic Party. It was Sevier who secured Arkansas’s bid for statehood, with President Andrew Jackson signing the bill making it the twenty-fifth state on June 15, 1836. Arkansas’s first legislature rewarded Sevier by electing him as one of the state’s first two U.S. senators.

At the pinnacle of his power in Arkansas, Sevier now became an important person in the Congress. According to historian Brian S. Walton, “Sevier entered the Senate in this, its age of glory, and conquered it…. He alone among Arkansas’ pre-Civil War senators achieved any prominence in the chamber.” During his twelve year tenure, Sevier chaired two major committees, Indian Affairs and Foreign Relations. His views reflected those of many on the frontier; he backed Jackson’s Indian removal policy and labored unsuccessfully to give free land away in the West to American homesteaders. Manifest Destiny had the Arkansas’s senator’s approval as he supported demands to take all of Oregon from the British in the mid-1840s. Sevier’s views on expansion were quite congruent with those of newly elected President James K. Polk. As Chair of the Foreign Relations Committee (1845–1848), he ushered the final Oregon Treaty through the Senate and vigorously supported the conflict with Mexico.

As Sevier’s power in the national capital waxed, his hold over Arkansas politics waned. As the Democrats controlled the Arkansas General Assembly in 1842, Sevier easily won reelection to the Senate, yet within weeks, the Arkansas legislature censured him for financial malfeasance regarding bonds associated with the failed Arkansas Real Estate Bank. Personal tragedy also struck when his wife died after a long illness on March 16, 1845. In March 15, 1848, Sevier resigned his seat in the U.S. Senate at the request of President Polk to serve as a commissioner implementing the final peace treaty with Mexico. Sevier became ill in Mexico, resigned as commissioner in June, and was back in Washington by July 13; he returned to his plantation in Pine Bluff (Jefferson County) by the end of August. Meanwhile, Solon Borland, the former editor of the state’s Democratic newspaper, had replaced him in the Senate. Borland was to hold the office until Sevier could reclaim it. Borland, however, built support for his own candidacy and stunned Sevier by defeating him by just four votes in the General Assembly election in November, 1848.

Already in poor health from his diplomatic stint in Mexico, Sevier never recovered from this political upset, and he died on December 31, 1848. He is buried in Mount Holly Cemetery in Little Rock.

For additional information:

Bolton, S. Charles. Arkansas, 1800–1860: Remote and Restless. Fayetteville: University of Arkansas Press, 1998.

Walton, Brian G. “Ambrose Hundley Sevier in the United States Senate, 1836–1848.” Arkansas Historical Quarterly 32 (Spring 1973): 25–60.

White, Lonnie J. Politics on the Southwestern Frontier: Arkansas Territory, 1819–1836. Memphis: Memphis State University Press, 1964.

Woods, James M. Rebellion and Realignment: Arkansas’s Road to Secession. Fayetteville: University of Arkansas Press, 1987.

James M. Woods

Georgia Southern University

Comments

No comments on this entry yet.