calsfoundation@cals.org

Alida Clawson Clark (1823-1892)

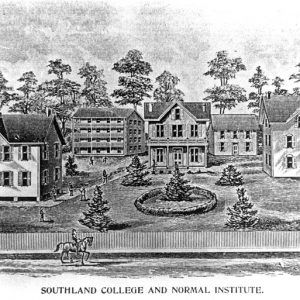

Alida Clawson Clark, an Indiana Quaker who co-founded Southland College, arrived in Arkansas with her husband, Calvin, in April 1864 on a wartime mission to provide material and spiritual comfort to formerly enslaved people while war raged in the rest of the state. After supervising a temporary orphanage and school for Black children in Union-occupied Helena (Phillips County), the Clarks moved their charges and school to a rural site near Helena, establishing what became Southland College (later Southland Institute), the first academy of higher education for African Americans west of the Mississippi River. She also founded Southland Monthly Meeting, the first predominantly Black Friends Meeting for Worship in more than two centuries of Quaker history.

Alida Clawson was born February 9, 1823, on a farm near Richmond, Indiana. She was one of nine children of William and Keziah Ward Clawson, who were among hundreds of Quakers who had migrated to southern Indiana from North Carolina to escape the practice of slavery. Clawson attended the Quaker academy in Plainfield, Indiana, and possibly other schools. In 1844, she married farmer and schoolteacher Calvin Clark, a distant cousin. For the next twenty years, they operated a family farm near Richmond, raising three daughters, only one of whom survived to adulthood. Before the Civil War, the Clarks were strong abolitionists and active members of the Whitewater Monthly Meeting of Friends. (For Quakers, “meeting” means recognized gathering of worshipers; a Monthly Meeting is made up of two or more local meetings.)

According to the U.S. Census for Wayne County, Indiana, the Clarks held more than $6,000 in real and personal property in June 1860. But, early in 1864, they left these holdings to answer the call of the Freeman’s Committee of Indiana Yearly Meeting to establish an asylum in Helena for lost or abandoned Black children.

Upon the Clarks’ arrival in Helena in early April 1864, sixteen Black children were placed in their charge; hundreds more followed. After caring for this first band of orphans, their next steps were to set up a school in a stable and to establish a Quaker meeting for worship.

After nearly two years, the orphanage and elementary school were—at the instigation of the local army commander, Colonel Charles Bentzoni, and with the assistance of the Fifty-sixth United States Colored Troops—moved to an eighty-acre site nine miles northwest of Helena. In this rural setting, Calvin and Alida worked for twenty years, she tending to the educational and spiritual aspects of the Southland school and Quaker meeting while her husband did the accounting and oversaw the college farm. The Clarks acquired considerable property near the school and, with their son-in-law Theodore Wright, established a family farm, which grew to 1,700 acres.

At Southland, Clark was teacher, minister, temperance crusader, and what today would be called the director of development. She wrote an unending stream of letters to Quaker journals and prominent, wealthy Friends in her efforts to improve public relations and raise money for Southland. Under her direction, the school’s enrollment grew, by 1880, to 300 local and boarding students studying in elementary, normal, and college divisions. In the early years, teachers were usually white Quakers, but eventually Black Southland graduates joined the faculty. Clark also aggressively brought new converts into Southland Monthly Meeting, which, in time, included two more subordinate meetings for worship. She envisioned Southland as the spiritual base for a great Black Yearly Meeting to bring Christian virtue and Quaker integrity to the rural population of the Arkansas Delta and beyond. While that dream never became reality, Clark lived to see Southland Monthly Meeting increase to nearly 400 souls, an extraordinary figure for a local Quaker congregation anywhere in the United States.

The Clarks’ final years at Southland were marred by internal disputes concerning academic standards, financial difficulties, and false accusations of mismanagement brought by a former teacher. Undoubtedly, these problems helped to prompt their retirement in 1886 to a small farm near the school where Clark died on March 14, 1892. Her legacies—Southland College (the name was changed to Southland Institute in 1915) and the Friends Meeting—continued to serve African Americans in Phillips County and the Delta until 1925. In the 1930s and 1940s, the African Methodist Episcopal Church operated what was then Walters-Southland Institute at the original site; this school never flourished and closed after World War II.

For additional information:

Friends Collection. Archives. Earlham College Libraries, Richmond, Indiana.

Kennedy, Thomas C. “Another Kind of Emigrant: Quakers in the Arkansas Delta, 1864–1925.” Arkansas Historical Quarterly 55 (Summer 1996): 199–220.

———. A History of Southland College: The Society of Friends and Black Education in Arkansas. Fayetteville: University of Arkansas Press, 2009.

———. “Rise and Decline of a Black Monthly Meeting: Southland, Arkansas, 1864–1925.” Arkansas Historical Quarterly 50 (Summer 1991): 115–139.

———. “Southland College: The Society of Friends and Black Education in Arkansas.” Arkansas Historical Quarterly 42 (Winter 1983): 207–238.

Kirkman, Dale P. “Southland College.” Phillips County Historical Quarterly 3 (Spring 1964): 30–33.

Selleck, Linda B. Gentle Invaders: Quaker Women Educators and Racial Issues during the Civil War and Reconstruction. Richmond, IN: Friends United Press, 1995.

Southland College Papers. Special Collections. University of Arkansas Libraries, Fayetteville. Finding aid online at https://uark.as.atlas-sys.com/repositories/2/resources/1609 (accessed September 22, 2023).

Thomas C. Kennedy

University of Arkansas, Fayetteville

Comments

No comments on this entry yet.