calsfoundation@cals.org

Action at Devil's Backbone

aka: Action at Backbone Mountain

aka: Action at Jenny Lind

| Location: | Sebastian County |

| Campaign: | None |

| Date: | September 1, 1863 |

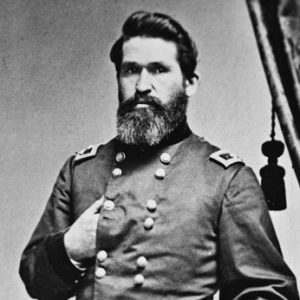

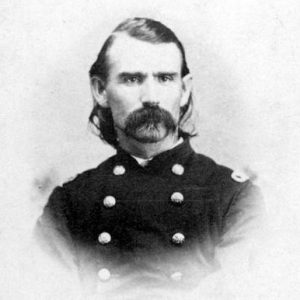

| Principal Commanders: | Colonel William F. Cloud, Major General James G. Blunt (US); Brigadier General William L. Cabell (CS) |

| Forces Engaged: | District of Southwestern Missouri, Department of the Missouri (detachment) (US); Cabell’s Brigade, Department of the Indian Territory (CS) |

| Estimated Casualties: | 2 (US); 5 (CS) |

| Result: | Union victory |

The Union victory at Devil’s Backbone secured the North’s capture of Fort Smith (Sebastian County) on September 1, 1863. Although fighting continued in the region, Fort Smith remained a Union base until the war’s end.

After driving other Confederate forces farther south into Indian Territory in late August 1863, Union Major General James G. Blunt rapidly turned toward Fort Smith. Blunt’s troops skirmished with Confederate Brigadier General William L. Cabell’s brigade southwest of Fort Smith on August 31. Cabell decided to retreat southeast and sent his baggage and ordnance wagons off that evening. Discovering this Confederate retreat the next morning, Blunt took an infantry regiment and captured Fort Smith without incident, while Colonel William F. Cloud led about 700 Union cavalry and artillery men in pursuit of Cabell.

After retreating down the road toward Waldron (Scott County), Cabell turned around to buy time for his slow-moving wagons to escape. His total force numbered 1,250, but probably not all participated in the ensuing action. Morale was a problem; some of Cabell’s troops were described as deserters, conscripts, and jayhawkers, with little interest in the Confederate cause. Cabell concealed a reliable cavalry regiment at the base of Devil’s Backbone, a ridge crossed by the road. Three unreliable cavalry units were stationed on the hillside beside the road, with an artillery battery and an infantry regiment posted a few hundred yards up the slope behind the cavalry.

At noon, Cabell drew first blood when Cloud’s advance guard blundered into the concealed cavalry regiment’s ambush. The advance guard’s survivors fell back in confusion as the Confederate battery began firing on the rest of Cloud’s arriving command. The Union troops deployed their artillery across the road; it went into action as Cloud’s cavalrymen dismounted, formed to either side of the road, advanced to the base of the ridge, and began to ascend the slope. The concealed Confederate cavalry regiment retired before this advance even though Cloud’s troops had not yet opened fire.

At this point, Cabell’s other units demonstrated their unreliability. An officer with Cabell’s infantry regiment recalled, “As the Yankees came in musket range of Cabell’s leading regiment, it stampeded without firing a shot and running into and through the two regiments in its rear, stampeded them and the whole combined mass ran through the left wing of [Cabell’s infantry regiment] and swept them off the field.” In an instant, Cabell’s force was reduced to one cavalry regiment, the battery, and part of the infantry regiment.

Cloud pushed his dismounted cavalrymen to within a quarter of a mile of the Confederate line on the ridge’s summit. The action degenerated into a small-arms and artillery skirmish of three hours. Cabell directed the fire of the Confederate battery as Cloud’s men made occasional demonstrations of attacking, but no attack materialized; the parties were content to trade fire without close combat.

The action claimed the lives of two Union troops; twelve were wounded, and two went missing. Confederate casualties included five killed, twelve wounded, and thirty captured.

When the action ended, both sides claimed victory. Cloud reported that the Confederates suddenly retreated during a suspension of Union gunfire. Cabell may have misinterpreted this suspension, because he reported that Cloud was repulsed and that the Confederates then withdrew. In any event, the Union held the field at the action’s conclusion. All contact ceased with Cabell’s withdrawal. He reached Waldron (Scott County) the next day, and Cloud returned to Fort Smith.

By capturing Fort Smith and defeating Cabell at Devil’s Backbone, the Federal forces gained a foothold in the Arkansas River Valley. From this base, Federal units would battle Confederate partisans, march to participate in the April 1864 Camden Expedition, and support Federal efforts in Indian Territory. While the later Action at Massard Prairie in July 1864 demonstrated Fort Smith’s vulnerability, it nonetheless remained a Federal outpost for the rest of the war.

For additional information:

“Battle for the Devil’s Backbone.” The Key 1 (Spring 1966): 7–10.

Britton, Wiley. The Civil War on the Border. Vol. 2. Ottawa, KS: Kansas Heritage Press, 1994.

Bryant, Michael. “The Battle of Backbone Markers: Which is Correct?” The Journal of the Fort Smith Historical Society 22 (September 1998): 2–12.

Cox, Dale. “Battle of Devil’s Backbone, Arkansas.” The Key 39 (2006): 26–32.

Wright, John C. Memoirs of Colonel John C. Wright. Pine Bluff, AR: Rare Book Publishers, 1982.

Frank Arey

Morrilton, Arkansas

Comments

No comments on this entry yet.