calsfoundation@cals.org

William Dollar and "Fed" Reeves (Murders of)

In October 1868, a white deputy named William J. Dollar and an African-American man named “Fed” Reeves were allegedly killed by the Ku Klux Klan in Drew County. Most sources indicate that the murders occurred on October 16, but an October 18 article in the Arkansas Gazette references an article about the murders published in the Monticello Guardian on October 10, so the killings may have happened earlier. William G. Dollar appears several times in public records. In 1850, he was thirty-five and living in Cumberland County in North Carolina. Living with him were his wife, Louisa, and three children with ages ranging from one to six. In 1856 and 1859, he received land patents totaling 120 acres in Drew County, and in 1860 he and his wife were living in Saline Township with eight children with ages ranging from one to twelve. There is no record of any Fed or Fred Reeves in Drew County.

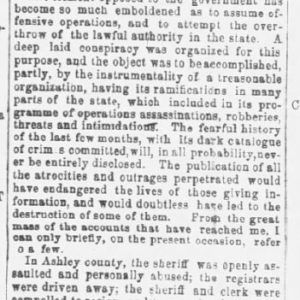

At the time of this crime, the situation in Arkansas was chaotic. Governor Powell Clayton, a radical Republican regarded by some as a “carpetbagger,” described the situation in a message published in the Arkansas Gazette on November 26: “The element opposed to the government has become so much emboldened as to assume offensive operations, and to attempt the overthrow of the lawful authority in the state.…The fearful history of the last few months, with its dark catalogue of crimes committed, will, in all probability, never be entirely disclosed.” He mentions the situation in Drew County, where a “deputy sheriff and negro [were] tied together and killed; a reign of terror inaugurated; men repeatedly threatened with death, and many compelled to vote against their wishes.”

Accounts of the murders were published in a number of national newspapers, and they were mentioned in Powell Clayton’s book The Aftermath of the Civil War in Arkansas. Clayton describes the events as follows: “Deputy Sheriff Dollar was serving a writ and was killed by a gang of some fourteen Ku Klux. Then, in order to make an impressive tableau, they killed ‘Fed’ Reeves, an unoffending negro, and tied the white man and negro together in the attitude of kissing and embracing, and left them in the public road where they remained for about two days. During this time, to gratify their curiosity, many people visited them and left them as they found them.” In his book White Terror: The KKK Conspiracy and Southern Reconstruction, historian Allen Trelease notes that Dollar was a Republican, and at the time the Ku Klux Klan was conducting a virtual war against “radical Republicans and newly enfranchised blacks” in Drew County. According to Trelease, Dollar and Reeves were in Dollar’s house when a group of Klan members appeared, forced them from the house, and led them about 300 yards from the house, where both “were cut down in a hail of gunfire.”

On October 22, the New Orleans Republican published a different and rather more fanciful account of the events surrounding the murders, taken from an October 17 dispatch from Pine Bluff (Jefferson County) to the Missouri Democrat. According to the Republican, “Mr. Dollar was out serving subpoenas; he was stopping with Mr. Grubbs. The Ku-Klux band came to Grubbs’s house about an hour before day; came into the house pretending to be friends, and drank peach brandy with Dollar and Grubbs, and commenced to dance. After dancing for some time, a signal was given, when they grabbed Dollar and took him off and shot him. Mr. Dollar was an old, wealthy and estimable citizen. This is one of the most diabolical and brutal acts of the Ku-Klux in this State.”

An article published in the Arkansas Gazette on October 18 seems to cast doubt on these interpretations of the murders. The article refers to the Little Rock Republican’s publication on October 17 of an article asserting that the account of the incident “has been fully corroborated by the following statement in the Monticello Guardian (dem.) of the 10th.” The Gazette summarizes the details of the murders but disagrees with the Guardian’s conclusions that the events were part of “the same old story that has accompanied the murder of every union man that has been killed in this state during the past four months.” According to the Gazette, the Republican offered “editorial prominence” to accounts of the murder, and asserted that the accounts were “fully corroborated” only because it “is supposed by the ravenous editor of the radical organ to be conclusive on the subject for the very substantial reason evidently that it is desirable that it should conclude that way.” According to the Gazette, “The public reputation is deeply outraged and the public are incensed. Lying radical tongues have been busy for four years misrepresenting the condition of affairs south, and the northern people in part believe the southern people a lot of ruthless savages.”

According to the Gazette, based on information published in the Monticello Guardian, by October 29 there were still no clues about who had murdered Dollar and Reeves. A group led by a deputy sheriff had arrested one man, but he was determined to be innocent and released. Speculation was that the perpetrators had instead come from another county. The article went on to say, “It is hoped that unceasing efforts will be made to ferret out, and punish the crime. The act we are proud to know is universally condemned by our citizens as an outrage upon law and humanity, justly deserving the severest punishment.”

In early November 1868, Powell Clayton declared martial law in Drew and nine other Arkansas counties. The area was divided into four military districts, with Brigadier General R. F. Catterson as head of the southwest district and Colonel S. W. Mallory of the southeast. The Arkansas Gazette reported on these militias on January 15, 1869, accusing them of widespread pillaging, including seizure of horses, pistols, dry goods, and mules. According to John Mortimer Harrell, on December 25 Mallory was ordered to arrest “the parties whose names have been sent to you.…It is absolutely necessary that some examples be made.” The same Gazette article indicated that, on December 27, some of Catterson’s forces, along with members of a home militia, had arrested and jailed a number of people. Harrell indicates that only one of these suspects, a young man named Stokes Morgan, was punished. He was accused of complicity in the murder of Dollar, who had reportedly been killed for “deserting his family and living with a negro woman.” Morgan was tried before a military commission, and although he had supposedly been thirteen miles away at the time of the murders, “he took no pains to make any defense.” The commission ruled that he should be discharged, but Catterson reversed this verdict and ordered him to be executed. He was first sent to the penitentiary at Little Rock (Pulaski County) but was then returned to Monticello and hanged. According to Clayton, the execution of Morgan had the desired effect, “resulting immediately in the flight from the State of thirteen desperadoes from the County of Drew, who were never permitted to return.”

On June 28, 2025, a memorial bench was dedicated in downtown Monticello (Drew County), in front city hall, to commemorate the murders of Dollar and Reeves.

For additional information:

“Arkansas.” New Orleans Republican, October 22, 1868, p. 1.

Clayton, Powell. The Aftermath of the Civil War in Arkansas. New York: Neale Publishing, 1915. Online at https://www.loc.gov/item/15004463/ (accessed March 6, 2024).

“The Dollar Murder.” Arkansas Gazette, October 29, 1868, p. 2.

“Governor’s Message.” Arkansas Gazette, November 26, 1868, p. 1.

Harrell, John M. The Brooks and Baxter War: A History of the Reconstruction Period in Arkansas. St. Louis, MO: Slawson Printing, 1893. Online at https://archive.org/details/brooksbaxterwarh00harr/page/n3/mode/2up (accessed March 6, 2024).

“Same Old Story.” Arkansas Gazette, October 18, 1868, p. 2.

“State News.” Arkansas Gazette, January 15, 1869, p. 2.

Trelease, Allen W. White Terror: The KKK Conspiracy and Southern Reconstruction. New York: Harper and Row, 1971.

Nancy Snell Griffith

Davidson, North Carolina

Comments

No comments on this entry yet.