calsfoundation@cals.org

Will McLendon (Reported Lynching of)

In many cases, newspapers across the country published reports on lynchings, which were then listed in books and other resources. In some cases, even though subsequent reports indicated that the lynching had not happened, initial accounts were not corrected. Such was the case with an African American man, Will McLendon of Woodruff County, who was reportedly lynched in August 1893. In his 1993 dissertation, citing an August 6 report in the Memphis Appeal Avalanche, historian Richard Buckelew commented on this presumed lynching, which he dated at August 5. In her 1894 book A Red Record, Ida Wells Barnett gave the date of the lynching as August 9. It seems, however, that McLendon actually died in jail in Newport (Jackson County) around August 7.

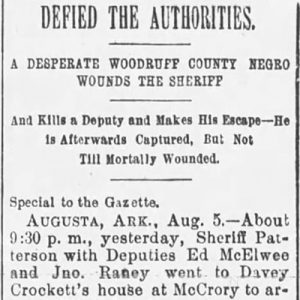

Details of McLendon’s alleged crime appeared in the Arkansas Gazette on August 6 and the Southern Standard on August 11. According to the Southern Standard, a theft was reported at the store of Jones & McElwee at Riverside (Woodruff County). Authorities suspected Will McLendon, described as nineteen years old and a “hard character.” McLendon left Riverside on the day after the theft. Receiving news that the alleged thief had been spotted at the railroad station in McCrory, on the night of August 4 a deputy sheriff named McElwee deputized John Rainey (referred to by the Gazette as John Raney) and started out for McCrory (Woodruff County). On the way, they met Marshall Patterson, the sheriff of Woodruff County, who decided to accompany them.

The men went to a house near McCrory, where they found McLendon. When they attempted to arrest him, McLendon drew a pistol and shot at Patterson, knocking him down. As he was running out of the house, McLendon shot and killed Rainey. Patterson recovered and fired three shots at McClendon, who then fled through town, where forty additional shots were reportedly fired at him. By 11:00 p.m., Patterson had arranged to have Rainey’s body taken care of.

Resuming the chase the following morning, he found McLendon walking along the railroad tracks. According to the Gazette, McLendon drew his pistol, but before he could fire, “a shower of lead was put into his body and his pistol dropped to the ground.” Sheriff Patterson then took him to the depot, where they got onto a train to either Augusta (Woodruff County) or Newport. They were reportedly met by a mob at Martin Junction (Woodruff County), but Patterson fended them off. Another crowd had gathered at Riverside, which was Rainey’s home, but the sheriff prevented them from stopping the train. Patterson eventually delivered McLendon to the jail in Newport for safekeeping.

According to Buckelew, on August 6 the Memphis Appeal Avalanche reported that McLendon had been lynched, “an event in which the press clearly approved of the mob’s actions.” Reporting that McLendon had been taken from Patterson on the way to Newport, the Appeal Avalanche noted: “The infuriated crowd were quick about their work. No large tree being convenient, McLendon, the murderer, was hanged to a sapling, whose bark was tender and whose years of experience are few. Yet that sapling served as well as a nobler tree and did its country service.”

The supposed lynching was picked up in other newspapers. On August 8, 1893, the Hopkinsville Kentuckian reported that McLendon (referred to here also as McLennon) had been lynched before he could reach jail. That same day, however, the Gazette reported that McLendon had died of his wounds, and that “contrary to the sensational rumors sent out from Woodruff County, no attempt was made to take him from the jail.”

Newspapers in Arkansas and elsewhere, however, failed to note McClendon’s death. As late as August 11, the Southern Standard and Forrest City Times were reporting that McLendon’s wounds were “of such a serious nature that it is thought he will die.” Other papers, including Vermont’s Essex County Herald and South Dakota’s Milbank Herald-Advance, reported that McLendon had been lynched. In the midst of such confusing accounts, it is often difficult to separate lynchings from other deaths and even executions in the historical record.

For additional information:

Buckelew, Richard. “Racial Violence in Arkansas: Lynchings and Mob Rule, 1860–1930.” PhD diss., University of Arkansas, 1999.

“Defied the Authorities.” Arkansas Gazette, August 6, 1893, p. 2.

“Died in Jail.” Arkansas Gazette, August 8, 1893, p. 4.

“Killed a Deputy Sheriff.” Forrest City Times, August 11, 1893, p. 8.

“Killed a Deputy Sheriff.” Southern Standard (Arkadelphia), August 11, 1893, p. 1.

“A Murderer Lynched.” Herald-Advance (Milbank, South Dakota), August 11, 1893, p. 3.

“News in General.” Essex County Herald (Island Pond, Vermont), August 11, 1893, p. 1.

Untitled. Hopkinsville Kentuckian, August 8, 1893, p. 2.

Wells, Ida B. A Red Record: Lynchings in the United States 1892–1893–1894. Chicago: Donohue & Henneberry, 1894.

Nancy Snell Griffith

Davidson, North Carolina

Comments

No comments on this entry yet.