calsfoundation@cals.org

Skirmish at Reed's Mountain

| Location: | Washington County |

| Campaign: | Prairie Grove Campaign |

| Date: | December 6, 1862 |

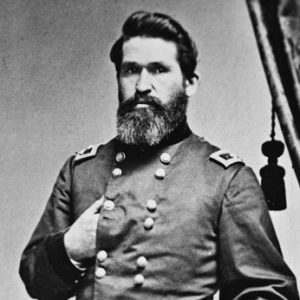

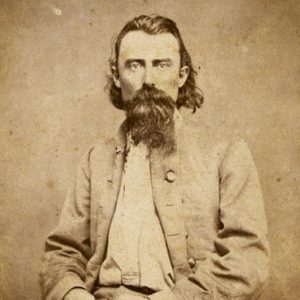

| Principal Commanders: | Brigadier General James G. Blunt, Lieutenant Colonel Owen A. Bassett (US); Brigadier General Joseph O. Shelby, Colonel James C. Monroe (CS) |

| Forces Engaged: | Second Kansas Cavalry, Eleventh Kansas Infantry, First Indian Home Guard (Kansas) Infantry (US); Shelby’s Brigade, First (Monroe’s) Arkansas Cavalry, Fourth (Carroll’s) Arkansas Cavalry (CS) |

| Estimated Casualties: | (Incomplete reports for both sides) 1 killed, seven wounded (US); 10 killed, 27 wounded (CS) |

| Result: | Tactical Union victory; strategic Confederate victory |

The series of maneuvers and skirmishes that took place on Reed’s Mountain on December 4–7, 1862, with the primary skirmish on December 6, relate directly to the aftermath of the Engagement at Cane Hill and serve as a prelude to the Battle of Prairie Grove.

After his tactical victory at Cane Hill (Washington County) on November 28, Major General Thomas C. Hindman hoped to rely on Reed’s Mountain to slow a persistent Federal pursuit and conceal his planned attack against the separated portions of the Army of the Frontier. Therefore, on December 3, Hindman ordered Brigadier General John S. Marmaduke to prepare a defensive stand, anchored at the approaches to the Cove Creek and Wire roads. Information gathered through reconnaissance and local informants, however, allowed Brigadier General James G. Blunt to deduce Hindman’s intent and telegraph for reinforcements as early as December 2.

During a morning patrol on December 4, Captain Avra P. Russell of the Second Kansas Cavalry discovered the Confederate presence on Reed’s Mountain near Cove Creek Road; Russell immediately established a picket outpost on the road and waited for an assault. Early on December 5, sharp skirmishing with cavalry and artillery from Brigadier General Joseph O. Shelby’s command threatened Russell’s flank, so he withdrew four miles to the foot of the mountain and re-formed his line before returning to camp. For the remainder of December 5, the Federals primarily reinforced their picket outposts along Cove Creek Road and attempted to reconnoiter the approach from Wire Road.

At 6:00 a.m. on December 6, Shelby’s dismounted brigade attacked a scouting party under Captain John Gardner of the Second Kansas Cavalry in the front and in both flanks with heavy fire at the junction of the Cove Creek and Cane Hill roads, with other Confederates in position on the Wire Road. Gardner slowly withdrew but maintained skirmish fire for two miles, formed a new line, and drove back the enemy. He maintained this position for thirty minutes and then withdrew to the foot of the mountain to await reinforcements.

Lieutenant Colonel Owen A. Bassett of the Second Kansas Cavalry, commanding the main line of skirmishers at the foot of the mountain, strengthened his left flank with 100 Native American reinforcements from Colonel Stephen H. Wattles’s First Indian Home Guard (Kansas) Infantry under First Lieutenant Albert F. Bicking. Bassett maintained his position until Blunt arrived on the scene and ordered skirmishers to the ledge of rocks near the summit and forced a Confederate withdrawal.

Colonel James C. Monroe’s undersized brigade, consisting of Monroe’s First Arkansas Cavalry and Colonel DeRosey Carroll’s Fourth Arkansas Cavalry, led the next Confederate assault. Initially stymied by superior Federal numbers in a strong defensive position, Monroe then received reinforcements from an infantry regiment and forced a confused Federal retreat. Rough terrain, however, prevented a vigorous Confederate pursuit.

With the arrival of Colonel Thomas Ewing and four companies of the Eleventh Kansas Infantry, the Federals attempted to use the concealed position under the ledge of rocks to draw the Confederates into an ambush. When this tactic failed, Ewing’s men withdrew to the foot of the mountain. By evening, however, Bassett ordered pickets to reoccupy the ledge of rocks.

After some additional contact, Federal pickets detected the approach of a large Confederate force up Cove Creek Road. Elements of this force attacked and slowly pushed back the Federal pickets. A Confederate cavalry regiment continued this assault but withdrew in confusion under heavy, close-range Federal fire. The Rebels approached again, fighting along the entire line for forty-five minutes, but they again withdrew. The force of these assaults, however, convinced the Federals that they faced superior numbers, and they withdrew from the ledge of rocks at dusk, after the action ceased.

By the evening of December 6, Hindman learned of Brigadier General Francis J. Herron’s imminent approach and devised a strategy to strike Herron before he could reinforce Blunt. At sunrise on December 7, Monroe’s brigade engaged the Federal pickets at the intersection of the Cove Creek and Cane Hill roads, with orders to hold their position as long as possible to screen Federal knowledge of a general Confederate withdrawal already underway.

This skirmish lasted until the earliest exchange of artillery at Prairie Grove (Washington County) announced the commencement of a larger battle. Between 9:00 and 10:00 a.m., Captain Arthur Gunther of the Second Kansas Cavalry reported the Confederate withdrawal toward Cove Creek. Bassett prepared to pursue until Blunt ordered him to move toward Fayetteville (Washington County) by way of Ross’s Mill as a rearguard to the column on its way toward the Battle of Prairie Grove. Bassett reported only one man killed and seven wounded, including two severely.

After withdrawing from Reed’s Mountain, Monroe reconnoitered Cane Hill until dark and then moved toward Prairie Grove, where he arrived after that battle’s conclusion. Reports of Confederate losses vary. Neither Marmaduke nor Shelby reported losses for Reed’s Mountain. Monroe reported a total of four killed and twelve wounded within his brigade. Captain Amaziah Moore of the Second Kansas Cavalry estimated the combined total of Confederate killed and wounded at twenty-one, plus twelve horses wounded, while Bassett estimated ten Confederates killed and twenty-seven wounded.

Both sides credited their opponent with numerical superiority at various moments and could justifiably claim a degree of victory at Reed’s Mountain, as each forced the other into at least one tactical withdrawal. In addition, the Confederate withdrawal on the morning of December 7, conducted to preserve their strategic goal of striking the individual portions of the Union armies, left the Federals temporarily in control of Reed’s Mountain until they likewise redeployed toward Prairie Grove. By then, however, Blunt had achieved his tactical goal of winning sufficient time for Herron’s arrival in northwestern Arkansas. The Skirmish at Reed’s Mountain, therefore, represents a tactical Union victory as well as a strategic Confederate victory.

For additional information:

Shea, William L. Fields of Blood: The Prairie Grove Campaign. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2009.

The War of the Rebellion: A Compilation of the Official Records of the Union and Confederate Armies. Series 1, Vol. 22, part 1. Washington DC: Government Printing Office, 1888.

Robert Patrick Bender

Eastern New Mexico University–Roswell

Comments

No comments on this entry yet.