calsfoundation@cals.org

Home Demonstration Clubs

Home demonstration clubs were an integral part of the U.S. Department of Agriculture Cooperative Extension Service, which was established during the early twentieth century as an experiment in adult education, providing agricultural demonstration work for men and home demonstration work for women. The home demonstration work taught farm women improved methods for accomplishing their household responsibilities and encouraged them to better their families’ living conditions through home improvements and labor-saving devices. Beyond just the realm of the individual family, the clubs also became sources of education and charity in communities.

On January 1, 1912, Emma Archer organized the first canning club work for girls in Mabelvale (Pulaski County). In 1916, Archer became Arkansas’s first state home demonstration agent. As such, she supervised experts in various areas as well as district supervisors. At the county level, one agent was tasked with developing the entire county’s program despite relatively limited modes of communication and transportation. The agent trained lay members, who in turn provided demonstrations to women throughout the county. Early on, the clubs were not racially integrated. African American agents were employed to work with Black women in counties with a large Black population, while white agents worked with Black clubs in the remaining counties.

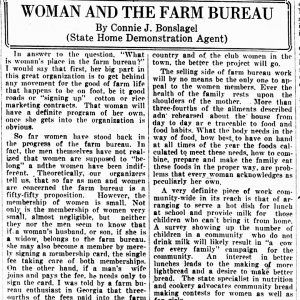

Within a few years of the program’s beginning, two notable women emerged to lead two separate but interrelated facets of the program: Connie J. Bonslagel and Mary L. Ray. Bonslagel, a Mississippi native, served as Arkansas’s state home demonstration agent from 1917 until her death in 1950. During her tenure, white membership grew from 2,083 in 1917 to a high of 64,863 in 1941. Ray was Negro District home demonstration agent from about 1918 until her death in 1934. Ray’s husband, H. C. Ray, served for many years as Negro District agricultural demonstration agent.

Although the official home demonstration program dealt with home improvement, labor-saving devices, and educational activities—such as gardening, canning, nutrition, and sewing—the women took their newly honed skills and reached out to their communities as sources of information and benevolence.

During World War I, members and agents took leadership roles as they demonstrated war cookery and food conservation in local communities. During the Great Influenza Epidemic of 1918, most of the sixty-eight home demonstration kitchens were converted into kitchens where soups and other foods were prepared to be sent out to suffering families. Arkansas’s home demonstration women also responded to the U.S. Food and Drug Administration’s call to eat less meat in order to provide food supplies needed to ameliorate widespread starvation in Europe. Women made cottage cheese and served it to their families in lieu of meat.

During the Flood of 1927, members canned hundreds of jars of vegetables and sent them to flooded counties; agents took an active role in refugee camps and hospitals as nutritionists and cooks. By 1928, agents reported on lay members’ contributions to life-saving hot lunch programs for children in rural schools.

The clubs were particularly active during the Great Depression. In 1934, the statewide organization began a tradition of providing thousands of jars and cans of vegetables to the struggling Arkansas Children’s Home and Hospital. Ruth Olive Beall, who became superintendent of the children’s home and hospital in 1934, commented several years later that the rural women’s contributions allowed the institution to remain open during that difficult year. As families moved to the countryside due to a lack of employment opportunities in cities, home demonstration members taught their new neighbors to garden and can. When newcomers were unable to learn the unfamiliar skills, the women canned additional jars or tins of food for them. On August 20, 1936, members and agents participated in a statewide Drought Recovery Day, in which they shared information on fall planting and the canning of meats and vegetables.

Mattress-making from home-grown cotton became a major project among club members during this time. The program grew exponentially as a way to use up surplus cotton, as profitable cotton prices had crashed along with the stock market at the beginning of the Depression. Agents and unpaid lay leaders provided training for thousands of families on relief rolls. By 1940, more than 137,000 mattresses had been made by and for these families, mostly from Federal Surplus Commodities Corporation cotton. The average cost per family was $0.28 for needles, twine, and thread.

In 1938, the Arkansas Council of Home Demonstration Clubs voted to undertake fundraising to build a sorority-type house for 4-H program girls at the University of Arkansas (UA) in Fayetteville (Washington County). After twelve years, the amount raised was not enough to build the house, so businessmen stepped in to supplement the women’s contribution. In 1951, forty students moved in, paying $35 per month in cash or commodities from their families’ farms. Alumnae of the 4-H House hold a reunion in Springdale (Washington and Benton counties) every August. These women have reported that most of them would not have been able to go to college without the 4-H House.

As Arkansas’s farmers depleted the soil due to the one-crop system in widespread use during the mid-twentieth century, the Extension Service’s live-at-home program encouraged farm families to grow their own food rather than depend solely on cash crops. During World War II, home demonstration clubs’ Committees on Preparedness made live-at-home inventories in their communities and then went out into neighborhood homes to encourage farm families to do a better job of food production.

Changes wrought by the war, however, harmed the statewide organization in ways from which it would never recover. Some 17,000 families left Arkansas’s farms during World War II. Many never returned. After the war, the emphasis changed to focus on younger women, including so-called “G.I. wives,” as well as urban women and women in the workforce.

In 1965, the segregated home demonstration work ended. In 1966, Black and white women came together within the newly reorganized Extension Homemakers Council, which continues in the twenty-first century as members focus on such topics as nutrition, health, and money management. They also continue the strong tradition of community service.

For additional information:

Arkansas Extension Homemakers Council. History of Home Demonstration Work in Arkansas, 1914–1965. N.p.: n.d.

Arkansas Extension Homemakers Council Oral History Program. David and Barbara Pryor Center for Arkansas Oral and Visual History. University of Arkansas, Fayetteville, Arkansas. Online here (accessed June 28, 2025).

Cantrell, Andrea. “Working Together and Helping Others: Washington County Women’s Extension Clubs.” Flashback 71 (Winter 2021): 154–167.

Hill, Elizabeth Griffin. “Legacies & Lunch: Home Demonstration Clubs.” July 2, 2014. Central Arkansas Library System, Little Rock, Arkansas. Video online at Butler Center AV/AR Audio Video Collection: Elizabeth Griffin Hill Lecture (accessed June 28, 2025).

———. A Splendid Piece of Work—1912–2012: One Hundred Years of Arkansas’s Home Demonstration and Extension Homemakers Clubs. N.p.: 2012.

Hogan, Mena. “A History of the Agricultural Extension Service in Arkansas.” MS thesis, University of Wisconsin, 1942.

Hogue, Erin. “To Create a More Contented Family and Community Life: Home Demonstration Work in Arkansas, 1912–1952.” PhD diss., University of Arkansas, 2017. Online at https://scholarworks.uark.edu/etd/1980/ (accessed June 28, 2025).

Home Demonstration Club Records. Special Collections. University of Arkansas Libraries, Fayetteville.

Jones-Branch, Cherisse. “African American Home Demonstration Agents in the Field and Rural Reform in Arkansas, 1914–1965.” In Women in Agriculture: Professionalizing Rural Life in North America and Europe, 1880–1965, edited by Linda M. Ambrose and Joan M. Jensen. Iowa City: University of Iowa Press, 2017.

———. Better Living by Their Own Bootstraps: Black Women’s Activism in Rural Arkansas, 1914–1965. Fayetteville: University of Arkansas Press, 2021.

———. “Empowering Families and Communities: African American Home Demonstration Agents in Arkansas, 1913–1965.” In Race and Ethnicity in Arkansas: New Perspectives, edited by John A. Kirk. Fayetteville: University of Arkansas, Press, 2014.

Lampkin, Sheilla. “A History of Extension Homemakers Clubs in Drew County.” Drew County Historical Journal (2012): 43–52.

Special Issue on Home Demonstration Clubs in Stone County. Heritage of Stone 42.1 (2018).

“The Mabelvale Home Demonstration Club.” Pulaski County Historical Review 14 (March 1966): 12–16.

U.S. Department of Agriculture Cooperative Extension Service. Record Group 33. National Archives at Fort Worth, Texas.

Elizabeth Griffin Hill

North Little Rock, Arkansas

I remember how much my grandmother depended upon this organization. It was her learning lab and her social group. She lived in Ash Flat, Arkansas. I was born in 1956, and she was still on the roll when she died in her 90s. The ladies even gave me a wedding shower!

As a young mother and homemaker in the ’60s, I was a member of the Home Demonstration Club in Memphis, Tennessee. Through the club, friendships were formed and lessons learned, and I add that some were learned the hard way. The members were very understanding and gentle in their corrections. Through failure we grow, and I grew a lot. For some reason memories came to mind (I am 80), and I wondered if the clubs were available today. That they have lasted speaks volumes about their value. Among my cherished recipes are two from the recipe contest. The dish often graces my table. As a child, I heard my mother speak of her participation in the Home Demonstration Club in Indiana. I am thrilled to learn the clubs are still alive and kickin’ and to learn of the wonderful contributions they have made.