calsfoundation@cals.org

Crossett Lumber Company

The Crossett Lumber Company (CLC) was Arkansas’s largest and most influential lumber company from its founding in 1899 until its merger with the Georgia-Pacific Company in 1962. It is notable for its growth alongside the company town of Crossett (Ashley County) and its early use of sustained-yield forestry in collaboration with Yale University’s School of Forestry.

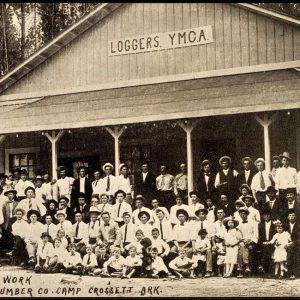

On May 16, 1899, Charles W. Gates, Edward Savage Crossett, and Dr. John W. Watzek—all from Davenport, Iowa—founded the Crossett Lumber Company in Ashley County in southeast Arkansas and Morehouse Parish in northern Louisiana. Stockholders named them president, vice president, and treasurer of the board of directors, respectively. Their first action was the purchase of 47,000 acres of land from the Michigan investment firm of Hovey and McCracken at seven dollars per acre. That same year, CLC was given the right to commence its lumbering plans. At first, the company expanded slowly as new railroad connections were being built, and no commercial timber was sold until 1902, by which time investors had spent $1 million starting the company. Its first pine mill, built in May 1899, was an enormous operation, with two band mills, dry kilns, a planer mill, and other equipment to smooth and then distribute the lumber. In 1905, a second pine mill similar to the first was built, and the company was soon producing 84 million board feet annually. CLC continued to develop new products that allowed company growth, such as a paper mill, silo, and chemical companies. These endeavors not only helped to eliminate waste but also allowed CLC to invest more in research and development programs to maintain the affordability of its products. These expansions spurred new railroad connections, with the Crossett Railway Company, a non-company railroad, connecting Crossett and the settlement of Stephens (now Milo, in Ashley County) ten miles north.

The company built houses, a school, and a church for the workers and their families; in 1903, all of this was incorporated as the company town of Crossett. An electric service quickly became available, and a Methodist church was dedicated in 1904. In 1906, the Crossett Observer began publication, and telephone service was introduced the following year. The town–company dynamic was the epitome of how these two establishments could work together successfully; during the Great Depression, CLC remained financially stable, and it supplied the government with lumber during World War II. In the 1940s, CLC focused on the expansion of the town, and many of its residents came to own rather than rent their houses.

At the time, the standard logging procedure was a “cut-and-get-out” strategy that resulted in many acres of useless land. However, because this “cutover” land was perfect for growing pine, in 1926, CLC hired a graduate of Yale’s School of Forestry, W. K. Williams, who helped the company begin a program of sustained yield. This involved ceasing the practice of cutting down trees as fast as they were growing, and then leaving the healthiest trees in an area to repopulate the soil; these techniques kept the forests alive, rather than destroying them. Such procedures were very progressive at the time in American forestry and had previously only been used in Germany. Soon, the United States Forest Research Station was founded, and CLC was tackling and solving problems in the 1930s that would not be regarded as environmental issues until the 1970s.

Rumors of a merger or sale emerged in 1960 after unrest among the company’s board members became public following the death of Edward S. Crossett’s son, Edward C. Crossett, in 1955, and the interest of his heirs in selling their stock. Many larger northern lumber companies had expressed interest in purchasing or merging with CLC, and stockholders were becoming worried about CLC’s stability. Although millions of dollars were spent in the late 1950s to modernize the company and give the impression of vitality, one of its board members, Peter Watzek, a relative of John Watzek, was instructed to conduct reports on companies with which a merger was possible. He also traveled to New York to meet with several merger prospects. Despite Watzek’s report that CLC was strong enough that a merger was not necessary, stockholders were still not satisfied. The announcement of a sale to Union Bag and Paper was made in May 1960, but, by the fall of that year, the plan had fallen through. For two years, business went on as usual at CLC, with a rise in earnings in 1961, but a sale was still pursued, and it was announced on April 18, 1962, that the Georgia-Pacific Company, one of the major corporations of the plywood industry, had reached a sale agreement with the Crossett stockholders. Transition was smooth because CLC’s general manager, William C. Norman, agreed to stay in his position. Georgia-Pacific assured the citizens of Crossett that their lives would not be greatly affected by the sale.

Despite CLC’s history of having a good relationship with the citizens of its company town, two major strikes occurred. The first one, in 1940, came several years after the company decided to recognize a local union but refused to let it open a union shop. Workers commenced a fifty-eight-day strike that brought the community’s economy to a near standstill until a compromise was reached with the help of a young reverend named Aubrey C. Halsell. The second strike occurred in 1985 during negotiations for a new contract that would force workers to work outside of their traditional job classifications. Workers disapproved of the changes, their pay, and the work expectations, and when they went on strike, Georgia-Pacific ordered that permanent replacements be sent in. This was the first time that permanent replacements had ever been used in the paper industry. Although it effectively ended the strike, it left many of the union workers bitter. The town was, and in many ways still is, divided because of these issues.

For additional information:

Balogh, George Walter. “Crossett: The Community, the Company, and Change.” Arkansas Historical Quarterly 44 (Summer 1985): 156–174.

———. Entrepreneurs in the Lumber Industry: Arkansas, 1881–1963. New York: Garland Publishing, Inc., 1995.

Buckner, John W. Wilderness Lady: A History of Crossett, Arkansas. Little Rock: Rose Publishing Company, 1979.

Darling, O. H. “Doogie,” and Don C. Bragg. “The Early Mills, Railroads, and Logging Camps of the Crossett Lumber Company.” Arkansas Historical Quarterly 67 ( Summer 2008): 107–140.

Minchin, Timothy J. “Torn Apart: Permanent Replacements and the Crossett Strike of 1985.” Arkansas Historical Quarterly 56 (Spring 2000): 31–58.

Moyers, David B. “Trouble in a Company Town: The Crossett Strike of 1940.” Arkansas Historical Quarterly 48 (Spring 1989): 34–56.

Reynolds, Russell R. The Crossett Story: The Beginnings of Forestry in Southern Arkansas and Northern Louisiana. General Technical Report SO-32. New Orleans: USDA Forest Service, Southern Forest Experiment Station, 1980.

Bernard Reed

Little Rock, Arkansas

My mother was born in 1917 in Crossett and lived there many years. Her father and grandfather worked at the lumber mill for many years. It was always referred to as the Gates Lumber Co. My mother’s grandfather (G. W. Dukes) died in Crossett 1941.