calsfoundation@cals.org

Arkansas Post

Arkansas Post was the first and most significant European establishment in Arkansas. In the colonial and early national periods, from 1686 to 1821, it served as the local governmental, military, and trade headquarters for the French, the Spanish, and finally the United States.

In return for serving in René-Robert Cavelier, Sieur de La Salle’s 1682 expedition, Henri de Tonti, a French officer born of Italian parents, received land and a trading concession at the juncture of the Arkansas and Mississippi rivers. In the summer of 1686, he arranged with the local Quapaw for Jean Couture, Jacques Cardinal, and four other Frenchmen to establish a trading post, where they would exchange French goods for beaver furs. They founded this first Arkansas Post near the Quapaw town of Osotouy in present-day Arkansas County.

The First Post

The Frenchmen built a wooden house and fence, the first French establishment west of the Mississippi. The settlement, consisting of six men and a hut with no priest, was referred to it as “aux Arcs,” meaning “at the home of the Arkansas,” one of the names for the Quapaw Indians. Eager for French trade and alliance, the Quapaw welcomed the Post and supported it throughout most of its history. Without Quapaw supplies and military assistance, the Post would not have survived.

On July 24, 1687, La Salle’s brother and Henri Joutel arrived at Arkansas Post, having fled across Texas after a mutiny killed La Salle. They were relieved to find that Couture and Cardinal were getting along well with their Quapaw hosts. However, the fur trade was not going well. The Quapaw were not traditionally beaver hunters and showed little interest in changing, and French colonial policies failed to encourage the western trading ventures. Therefore, there was little trade on the Arkansas River in the Post’s early years.

Beginning in 1699, with the support of Louis XIV, the French began to invest resources in Louisiana. The Arkansas Post’s location near the Mississippi River meant it would play an important role in commerce and Indian diplomacy. In 1717, John Law’s Company of the West received the charter for Louisiana trade, and Law himself acquired a personal concession on the lower Arkansas River in 1720. His plan was to establish a military post and create an agricultural colony that would sell crops to the soldiers at Arkansas Post, as well as New Orleans and French Illinois. To work the land, his company recruited European settlers and indentured servants and bought African slaves. In the summer of 1721, nearly 100 slaves and indentured servants whom Law had sent arrived at the mouth of the Arkansas River to prepare the way for the mostly German settlers to whom Law had granted land. By 1723, Lieutenant Avignon Guérin de La Boulaye, with thirteen soldiers, took command of Arkansas Post.

Before the settlers could arrive, however, investors’ hopes for easy riches in Louisiana began to wane, and Law’s company went under. The slaves and most of the servants were moved to plantations closer to New Orleans, and in 1724, the Company of the West withdrew the garrison from Arkansas Post. Still, some of the former indentured servants, freed by Law’s bankruptcy, stayed to hunt, trade, and farm fields given to them by the Quapaw, so the French presence continued in the Arkansas region.

For the next few decades, the Post was occupied sporadically by soldiers and priests. Father Paul du Poisson became the Post’s resident priest in July 1727, but in 1729, he died in a Natchez Indian attack on the French post at Natchez, where he was visiting. In 1731, the colonial Louisiana government again assigned a dozen soldiers to Arkansas Post. Their commandant, First Ensign Pierre Louis Petit de Coulange, built the first substantial Post structures—a house for the commandant, soldiers barracks, a powder magazine, and a prison. All were built with vertical posts and probably bark roofs. From 1731 on, Arkansas Post was a center of colonial trade and diplomacy with the Quapaw and other Indians, including Osage, Caddo, Chickasaw, and other bands that came to hunt and trade in the region.

The Second Post

The Post suffered its first military assault on May 10, 1749, in the middle of a French-Chickasaw war. Chickasaw Chief Payamataha and 150 warriors attacked the settlers who lived outside the Post. The Chickasaw killed several French men and captured eight French women and children. Once the other settlers had escaped into the fort, the Chickasaw retreated with their captives. In response to the attack, Commandant Ensign Louis Xavier Martin de Lino moved the Post a few miles up the Arkansas River to be farther from the Chickasaw and closer to the Quapaw, who had moved their towns closer together upstream just before the attack. (The new location, at the bluffs called Écores Rouges, is the site of the Arkansas Post National Memorial.) The next commandant, Captain Paul Augustin Le Pelletier de La Houssaye, built an elaborate Post in the new location. It consisted of a barracks, a powder magazine, a prison, a storehouse and hospital, a bake house, a latrine, and an imposing building that housed the commandant, the priest, and a chapel, all protected by an eleven-foot-high stockade.

In 1756, just five years after La Houssaye completed the new Post, the next commandant, Captain Francois de Reggio, evacuated the elaborate construction. In order to protect the fort, La Houssaye had placed it too far from the Mississippi River for it to see and respond to British and Indian attacks on French convoys once the Seven Years’ War began.

The Third Post

The French moved the Post back down the Arkansas River about ten miles from the Mississippi River, in what is now Desha County. In this latest configuration, a stockade surrounded the commandant’s house, barracks, powder magazine, commissary, and a building to house visiting Indian delegations.

In 1763, after the French lost the Seven Years’ War, they surrendered the half of Louisiana that lay east of the Mississippi to the British; they had already given the western half, including Arkansas Post, to their ally Spain. The resident French traders and settlers remained, but Spanish troops occupied the Post in de Reggio’s site. The Spanish had difficulty adjusting to the diplomatic requirements of this frontier Post, where Indians and French far outnumbered the handful of Spanish soldiers. In 1772, Spanish Commandant Fernando de Leyba tried to enforce his superiors’ orders to reduce expenses on gifts and feasts for the Quapaw and to gain power over the Frenchman who interpreted between him and the Quapaws. In response, Quapaw Chief Cazenonpoint threatened to “put the knife to the post.” Leyba agreed to most of the Quapaw’s demands for goods, and the Post was saved.

The Fourth Post

In 1778, Spanish King Carlos III decided to take advantage of the American Revolution to declare war against his British rival. In 1779, to avoid flooding, Spanish Commandant Balthazár de Villiers moved the Post back to Écores Rouges. At first, his new Post did not even have a real fort, but fighting among the British, Spanish, and various Indian groups resulting from the American Revolution made local French settlers fear a Chickasaw attack. The settlers insisted on building a fort where they could seek protection. Villiers named it Fort Carlos III for his king.

The soldiers and settlers would soon be glad for the new fort when Chickasaw and British forces attacked in the westernmost battle of the Revolutionary War. The British and the American rebels had already made peace, but violence was continuing on the Mississippi. On April 17, 1783, a force of at least sixty British men, a dozen Chickasaw, and a few African Americans, led by Scottish trader James Colbert, attacked. To defend the Post, the commandant, Captain Jacobo Du Breuil, had only thirty Spanish soldiers, four Quapaw, and a handful of neighboring French settlers. Knowing that the attackers had little fear of the few Europeans protecting the Post, Du Breuil ordered his men to “yell like attacking Indians.” To give credence to the pretense that Indians were defending the fort, one of the four Quapaw ran into the midst of the attackers and threateningly planted a tomahawk in the ground. Believing the deception, Colbert’s forces fled, taking the prisoners they had captured. The next day, Quapaw Chief Angaska crossed the Mississippi River with 100 Quapaw and twenty Spanish soldiers and persuaded Colbert to surrender most of the prisoners.

Territorial Years through the Civil War

In 1800, Spain retroceded Louisiana to Napoleon, but the French did not reoccupy the colony. Thus, in 1804, after the Louisiana Purchase of the previous year, Spanish troops transferred the Post to the United States. That year, the United States established a military presence at Arkansas Post, staffed by Lieutenant James Many, a sergeant, two corporals, and fourteen soldiers. The next year, John B. Treat opened an official U.S. trading factory there, and it operated until 1810. Even after the factory closed, Arkansas Post remained an important center of settlement, business, and governance. After Jean Lafitte’s espionage mission on behalf of Spain in 1816, he advised that Americans would continue expanding westward and that Spain should focus upon their holdings in Mexico. In 1817, Frenchman Frederick Notrebe had established himself as a businessman in the area and was one of the first to set up a cotton plantation with slave labor. When Arkansas became a territory in 1819, Arkansas Post, as its largest and most important town, became its capital. As settlers moved into regions north, west, and southwest of the Post, however, the population center shifted from the Post. In 1821, the capital moved to the new town of Little Rock (Pulaski County).

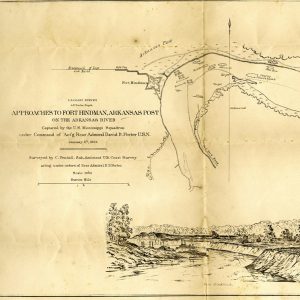

Arkansas Post rose to prominence again briefly during the Civil War. In the fall of 1862, Confederate forces chose its strategic location near the Mississippi to build Fort Hindman. The Post’s success in disrupting Union communication and supply lines led to a Union attack on January 11, 1863. The Post’s 5,000 troops were greatly outnumbered by the Union’s 32,000 infantry and 1,000 cavalry. After heavy attack from Union gunboats, the Confederate troops surrendered. The fort was destroyed, along with the remaining houses from the French and Spanish periods.

The Post Site Today

The Écores Rouges site of Arkansas Post became an Arkansas State Park in 1929 and a National Memorial in 1960, thanks to a bill presented to Congress by William Frank Norrell. Today, the National Park Service operates a visitor center and museum with displays on the Post’s history and archaeology, sixteen miles north of Dumas (Desha County).

For additional information:

Arnold, Morris S. The Arkansas Post of Louisiana. Fayetteville: University of Arkansas Press, 2017.

———. “Barthélémy Dit Charlot, a Colonial Arkansas Métis and Voyageur.” Arkansas Historical Quarterly 74 (Spring 2015): 1–17.

———. Colonial Arkansas, 1686–1804: A Social and Cultural History. Fayetteville: University of Arkansas Press, 1991.

———. “François Ménard, a Colonial Arkansas Marchard and Habitant.” Arkansas Historical Quarterly 74 (Winter 2015): 303–326.

———. “The Métis People of Eighteenth- and Nineteenth-Century Arkansas.” Louisiana History 57 (Summer 2016): 261–296.

———. The Rumble of a Distant Drum: The Quapaws and Old World Newcomers, 1673–1804. Fayetteville: University of Arkansas Press, 2000.

———. “The Soldiers of France in Colonial Arkansas.” Arkansas Historical Quarterly 80 (Winter 2021): 403–435.

———. Unequal Laws unto a Savage Race: European Legal Traditions in Arkansas, 1686–1836. Fayetteville: University of Arkansas Press, 1991.

Bearss, Edwin C., and Lenard E. Brown. Arkansas Post National Memorial. Washington DC: Office of History and Historic Architecture, 1971.

Coleman, Roger E. The Arkansas Post Story: Arkansas Post National Memorial. Santa Fe: National Park Service, 1987. Online at https://npshistory.com/publications/arpo/history/index.htm (accessed January 15, 2025).

Crane, Verner W. “The Tennessee River as the Road to Carolina: The Beginnings of Exploration and Trade.” Mississippi Valley Historical Review 3 (June 1916): 3–18.

DeBlack, Thomas A. With Fire and Sword: Arkansas, 1861–1874. Fayetteville: University of Arkansas Press, 2003.

Din, Gilbert C. “Arkansas Post in the American Revolution.” Arkansas Historical Quarterly 40 (Spring 1981): 3–30.

———. “The Spanish Fort on the Arkansas, 1763–1803.” Arkansas Historical Quarterly 42 (Autumn 1983): 271–293.

Dubuisson, Ann. “François Sarazin: Interpreter at Arkansas Post during the Chickasaw Wars.” Arkansas Historical Quarterly 71 (Autumn 2012): 243–263.

DuVal, Kathleen. “The Education of Fernando de Leyba: Quapaws and Spaniards on the Border of Empires.” Arkansas Historical Quarterly. 60 (Spring 2001): 1–29.

———. The Native Ground: Indians and Colonists in the Heart of the Continent. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 2006.

Faye, Stanley. “The Arkansas Post of Louisiana: French Domination.” Louisiana Historical Quarterly 26 (July 1943): 633–721.

———. “The Arkansas Post of Louisiana: Spanish Domination.” Louisiana Historical Quarterly 27 (July 1944): 629–716.

Key, Joseph Patrick. “The Calumet and the Cross: Religious Encounters in the Lower Mississippi Valley.” Arkansas Historical Quarterly 61 (Summer 2002): 152–168.

Mattison, Ray H. “Arkansas Post—Its Human Aspects.” Arkansas Historical Quarterly 16 (Summer 1957): 117–138.

Mosenthin, H. Glenn. “Thomas Nuttall’s 1819 Observations of Arkansas Post.” Grand Prairie Historical Bulletin 63 (April 2020): 36–46.

Sjostrom, Kristine L. Fernando de Leyba (1734–1780): A Life of Service and Sacrifice. Seville: 2022.

Toudji, Sonia. “‘The Happiest Consequences’: Sexual Unions and Frontier Survival at Arkansas Post.” Arkansas Historical Quarterly 70 (Spring 2011): 45–56.

Kathleen DuVal

University of North Carolina, Chapel Hill

European Exploration and Settlement, 1541 through 1802

European Exploration and Settlement, 1541 through 1802 Louisiana Purchase through Early Statehood, 1803 through 1860

Louisiana Purchase through Early Statehood, 1803 through 1860 Arkansas County Map

Arkansas County Map  Arkansas Post; 1689

Arkansas Post; 1689  Arkansas Post Cannon

Arkansas Post Cannon  Arkansas Post Dedication

Arkansas Post Dedication  Arkansas Post First Legislature Marker

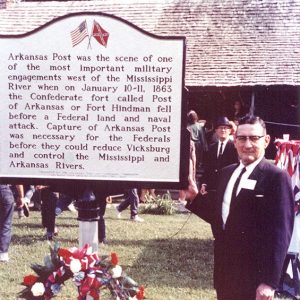

Arkansas Post First Legislature Marker  Arkansas Post Marker

Arkansas Post Marker  Arkansas Post National Memorial

Arkansas Post National Memorial  Entering Arkansas Post National Memorial

Entering Arkansas Post National Memorial  Arkansas Post Overlook

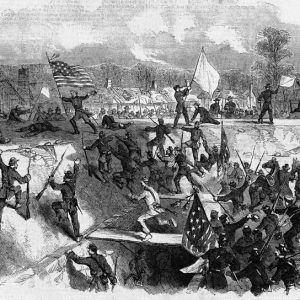

Arkansas Post Overlook  Battle of Arkansas Post

Battle of Arkansas Post  Battle of Arkansas Post

Battle of Arkansas Post  Battle of Arkansas Post

Battle of Arkansas Post  Henri de Tonti

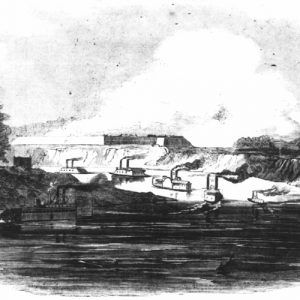

Henri de Tonti  Fort Hindman Approaches

Fort Hindman Approaches

Comments

No comments on this entry yet.