calsfoundation@cals.org

Arkansas Freeman

The Arkansas Freeman, which began publication on August 21, 1869, was the first newspaper in Arkansas printed by an African American and focusing upon the black community. It was in publication for less than one year, having become symptomatic of the divisions within the Republican Party, particularly where African Americans were involved.

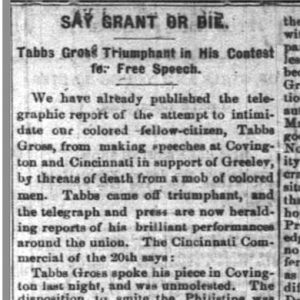

The idea to found a black press was approved on June 20, 1869, by a committee of African Americans, led by local advocate Jerome Lewis, at Wesley Chapel Methodist Church on the campus of Philander Smith College; a dinner was later held at the City Hall of Little Rock (Pulaski County) to raise funds to establish a newspaper. The committee included several ministers and community leaders who felt that their concerns were not printed in the city papers such as the conservative Daily Arkansas Gazette or the Morning Republican, the official press of the radical Republican Party to which many African Americans subscribed. The Reverend Tabbs Gross, an ex-slave from Germantown, Kentucky, stated in his prospectus that black citizens in the state needed a “faithful and reliable newspaper, devoted particularly to their interests, and conducted and controlled by men of their own race and color.” White Republican newspapers were enraged, generally, while the Gazette editorialized that, while a black newspaper would be second only to the Emancipation Proclamation for Arkansans of African descent, the race was too illiterate and naive to handle such a challenge.

Subscriptions for the new paper began on June 28, 1869, with Gross as publisher. However, many blacks turned their backs on him after having several meetings with whites who discouraged them from aligning with the editor and entrepreneur. Opponents even suggested that the Arkansas Freeman could somehow have them enslaved again. In spite of these and other allegations of bribery and thievery, as well as rumors about his character, Gross’s first issue, which bore the motto “Devoted to the Interests of the Colored People of Arkansas,” was successfully published. He received endorsements from local citizens in Little Rock, as well as others from the Fort Smith (Sebastian County) New Era, the Bentonville (Benton County) Republican Traveler, and the Gazette. However, little attention was given to the Arkansas Freeman in other cities, and for most issues, Gross paid out of his own pocket to have the paper printed and published.

Gross’s editorial positions were clearly laid out. His main purpose, he declared, was to use his newspaper as a vehicle to assist his people in their pursuits of true freedom, knowledge, justice, enlightenment, and prosperity. He wrote that his newspaper would “strike off the fetters that bind our fellow men in slavery or bondage, everywhere, whether it be the poor African slave of Cuba and Brazil, or our own white fellow-citizens of the south, who are unjustly deprived of many of the rights and privileges we enjoy.” This type of rhetoric turned the radicals further against him.

Each issue of the publication urged African Americans to do more for the betterment of their population. Gross encouraged them to seek political positions, both locally and statewide. He warned readers against being cheated by employers with their wages and salaries. He opposed Chinese immigration, which he believed took employment away from black people. He also wrote emphatically of his disapproval of convict labor.

By December, 1869, Gross had purchased press and type equipment from a Methodist newspaper, and the Freeman was, seemingly, progressing. However, Gross suddenly closed down the business and went to Memphis, Tennessee, where he attempted to raise funds for his press. While Gross was away, James C. Akers, a news correspondent from the Cincinnati Commercial and former assistant editor of the Colored Citizen, moved to Little Rock and literally took possession of the Freeman, stating that he had purchased the paper from Gross in Memphis. In February 1870, upon his return to Little Rock, Gross sued Akers for damages; he also brought a lawsuit against the Republican newspaper for making false allegations against him. In his absence from Little Rock, this newspaper’s editor attempted to denounce and ruin him publicly by alleging that “the newspaper was defunct, that Gross had secured the funds to underwrite it by misrepresentation and falsehood, and when he could no longer raise money in Little Rock, he had gone east to swindle others with a forged letter of recommendation.” None of these allegations were proven to be true. (Gross also sued the publishers/owners of the Republican, John G. Price and James H. Barton, but the case was dismissed.) Gross recovered no damages, but on March 19, 1870, the Freeman reappeared with him remaining as editor and owner.

By the summer of 1870, the Arkansas Freeman had come to an end, the victim of divisions within the Republican Party, which reached major political significance in the election that year. Yet, although short-lived, this newspaper proved important to black Arkansans who otherwise might not have been heard, and it broke ground for the over 100 black state news publications that followed. As Daniel F. Littlefield Jr. and Patricia Washington McGraw have written, “Its very destruction by the local power structure it had attacked proved that the black press could be a powerful dissenting voice which had to be dealt with by those in power.”

For additional information:

Arkansas Freeman. Microfilm. Arkansas History Commission, Little Rock, Arkansas.

Littlefield, Daniel F., Jr., and Patricia Washington McGraw. “The Arkansas Freeman, 1869–1870: Birth of the Black Press in Arkansas.” Phylon 40.1 (1979): 75–85.

Neal, Diane. “Seduction, Accommodation, or Realism? Tabbs Gross and the Arkansas Freeman.” Arkansas Historical Quarterly 48 (Spring 1989): 57–64.

Patricia Washington McGraw

Little Rock, Arkansas

The Arkansas Freeman

The Arkansas Freeman  Tabbs Gross Article

Tabbs Gross Article

Comments

No comments on this entry yet.