calsfoundation@cals.org

Tabbs Gross (1820–1880)

Tabbs Gross was a former enslaved man who, as a lawyer and newspaper publisher, played an active role in Arkansas politics during Reconstruction. A political gadfly, he worked hard to secure greater influence within the Republican Party for the newly freed and enfranchised African American population.

Tabbs Gross was born a slave in Kentucky in 1820. Purchasing his freedom prior to the Civil War, he moved to Cincinnati, Ohio, where he aided slaves using the Underground Railroad, both there and in New England. He also served in Cincinnati’s Black Brigade during the war. After the war, Gross continued his efforts on behalf of the former slaves, serving as the head of a local “Committee to Get Homes for Refugees.” He soon decided to help in the reconstruction of Arkansas, moving to the state in 1867.

In the summer of 1869, Gross began publication of the Arkansas Freeman, a newspaper based in Little Rock (Pulaski County)—and the first paper in the state to be owned and edited by an African American. Seeking to give voice to the growing Black discontent with the lack of Republican patronage, as well as their limited voice in Republican Party matters, Gross had secured the backing of a group of bBlack leaders and launched the paper. He pledged to work for both universal suffrage and universal amnesty, while also encouraging greater African-American immigration to Arkansas from the states to its east.

Seeking to expand his influence in hopes of playing an ever greater role in the developing plans for Reconstruction, in October 1869, he helped to found the short-lived Press Association of Arkansas, a group that sought to give the state’s newspapers broader influence. That same year, Gross found himself in the middle of a developing battle between the state’s Republican and Democratic parties, entities that were struggling with how to treat the newly enfranchised Black population.

From the outset, as head of the first Black-owned newspaper in the state, Gross was critical of the Republican Party’s treatment of Black members, and he agitated forcefully for greater access to the party’s inner circles—as well as governmental offices and jobs—for the state’s African Americans. Seeking at once to pressure the Republicans and reach out to the state’s Democrats, Gross supported the restoration of rights to former Confederates, expressing his belief that it would help facilitate reunification of the nation. The stance proved highly controversial, and he was widely criticized within the Republican Party. At the same time, he started a debate in the area’s white newspapers over the issue. While his efforts are generally believed to have secured some greater access for African Americans in Republicans circles, his continuing, almost harassing tone toward the Republican Party, put the newspaper at risk at a time when many papers survived financially only because of government printing contracts bestowed on what were essentially house organs for the parties.

Gross did not limit his hectoring tone to these issues; rather, he accused Governor Powell Clayton of encouraging the importation of cheap Chinese labor from California in an effort to depress the job market and leave the newly liberated freedmen dependent upon the state, while also accusing the leaders of the state’s official Republican newspaper, the Little Rock Republican, of corruption. While Gross felt he was being true to the paper’s motto—“Dedicated to the interests of the Colored People of Arkansas”—he ended up sabotaging the paper’s financial situation, with the state Republican Party dropping its support. Unable to secure a firm or consistent level of backing from other sources, it stumbled through a period of irregular publication before finally folding in 1870.

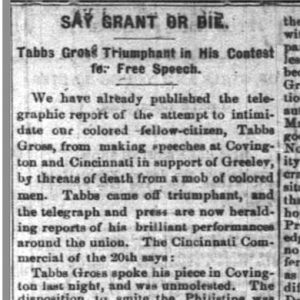

Gross continued to be an active, if often contrary, voice in the Republican Party. He served as vice president of the Liberal Republican state convention in Little Rock in 1869, a gathering at which plans were laid to take control of the party in the 1870 elections. He continued to be associated with the liberal wing of the Republican Party, aligning with the Brindletail faction of the Arkansas GOP and then following its lead by not only supporting the Liberal Republican faction’s nomination of publisher Horace Greeley for president in 1872, but also actively campaigning on Greeley’s behalf. Later, Gross served as a delegate to the state Republican convention in 1876. That same year, he personally entered the electoral arena, narrowly losing a race for a state legislative seat.

Following that defeat, Gross decided to focus on the practice of law, although he did make one final foray into the political arena, running as a Republican in an unsuccessful bid for county judge in Pulaski County in 1878. Having been admitted to practice by the Supreme Court of Arkansas in 1869, Gross established a partnership with the influential attorney Mifflin Gibbs, a mentor to many of the state’s Black politicians and lawyers. That partnership lasted for about a year, after which Gross returned to a solo practice.

Gross died of tuberculosis on January 10, 1880.

For additional information:

Kilpatrick, Judith. “(Extra)Ordinary Men: African American Lawyers and Civil Rights in Arkansas before 1950.” Arkansas Law Review 53, no. 2 (2000): 299–399. Online at http://arkansasblacklawyers.uark.edu/articles/ExtraORDINARYMEN.pdf (accessed October 20, 2020).

Littlefield, Daniel F., Jr., and Patricia Washington McGraw. “The Arkansas Freeman, 1869–1870: Birth of the Black Press in Arkansas.” Phylon 40, no. 1 (1979): 75–85.

Neal, Diane. “Seduction, Accommodation, or Realism? Tabbs Gross and the Arkansas Freeman.” Arkansas Historical Quarterly 48 (Spring 1989): 57–64.

“Tabbs Gross.” Arkansas Black Lawyers http://arkansasblacklawyers.uark.edu/lawyers/tgross.html (accessed October 20, 2020).

William H. Pruden III

Ravenscroft School

Civil War through Reconstruction, 1861 through 1874

Civil War through Reconstruction, 1861 through 1874 Law

Law Mass Media

Mass Media Tabbs Gross Article

Tabbs Gross Article

Comments

No comments on this entry yet.