calsfoundation@cals.org

Monticello (Drew County)

County Seat

| Latitude and Longitude: | 33º37’44″N 091º47’27″W |

| Elevation: | 298 feet |

| Area: | 10.89 square miles (2020 Census) |

| Population: | 8,442 (2020 Census) |

| Incorporation Date: | December 20, 1852 |

Historical Population as per the U.S. Census:

|

1810 |

1820 |

1830 |

1840 |

1850 |

1860 |

1870 |

1880 |

1890 |

1900 |

|

– |

– |

– |

– |

– |

– |

– |

891 |

1,285 |

1,579 |

|

1910 |

1920 |

1930 |

1940 |

1950 |

1960 |

1970 |

1980 |

1990 |

2000 |

|

2,274 |

2,378 |

3,076 |

3,650 |

4,501 |

4,412 |

5,085 |

8,259 |

8,116 |

9,146 |

|

2010 |

2020 | ||||||||

|

9,467 |

8,442 |

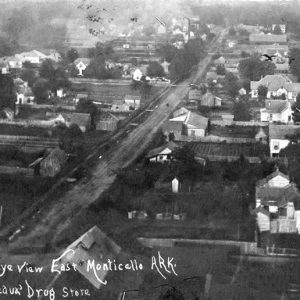

Monticello is the largest town in southeast Arkansas south of Pine Bluff (Jefferson County). Its history is one of continued growth and prosperity. Located at the intersection of two major roads and served early by railroads, it became an enduring commercial hub. A diversified infrastructure consisting of commerce, agriculture, and the timber industry created a strong foundation and sustained the town’s growth. The town also became an important educational and medical center.

Louisiana Purchase through Early Statehood

The first center of business and county court were at nearby Rough and Ready Hill, which was settled by 1836. Soon after Drew County formed in 1846, leading citizens decided that a new town should be built for the county seat. In 1849, Fountain C. and Polly Austin, early settlers, donated eighty-three acres for the town site. It is popularly believed that the citizens named the town after Thomas Jefferson’s Virginia estate.

The first courthouse was constructed in 1851 on the court square in the center of town. A second building replaced it in 1857. Lots were donated in the early 1850s for building Baptist, Methodist, and Presbyterian churches. Lots were also set aside for a male academy, a female academy, and a cemetery. A library was established in the courthouse in 1857. The earliest newspaper, the Sage of Monticello, began publishing in 1857. Among the pre–Civil War establishments were G. W. Simms & Co. General Merchandise, I. A. Price Dry Goods, M. A. Wilson & Co., Charles Millerd & Alexander Hale Contractors, Henry Lephiew Grocery & Liquor, M. H. Burks & Bro. Hardware, Lephiew & Duval Grocery & Liquor, and Dr. H. F. Bailey Drug Store.

Civil War through the Gilded Age

Commercial progress continued until the Civil War. The town witnessed three minor skirmishes in 1864 (January 13–14, March 18, and September 9–11) and three in 1865 (January 26–31, March 21–23, and May 23–27). They all concerned Union forces raiding for supplies and artillery and looking for Confederate soldiers. On one occasion, they entered Colonel William F. Slemons’s house to search for him, but he eluded them by hiding in a hotel loft. Rodger’s Female Academy, established in 1857, was used as a Confederate hospital. The Confederates used Phi Kappa Sigma Male College as a storehouse for supplies. Union forces burned the building in 1865, though the Union occupied the town. The last skirmish to occur in Monticello happened after the formal surrender of the Confederacy. Word had not yet arrived that the war had ended.

The Reconstruction period witnessed the organization of the Ku Klux Klan in the county in retaliation against “carpetbagger” rule. Officials and citizens reached an agreement that whites would continue serving as county officials and African Americans would be elected representatives. Two prominent black citizens, Curl Trotter and Lynn L. Brooks, are given credit for helping ease local tensions.

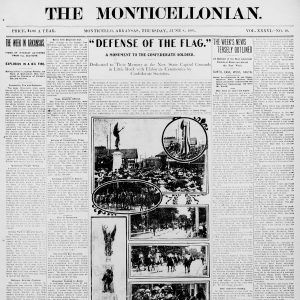

A newspaper, the Monticellonian, was established in 1870; it was followed by the Drew County Advance in 1892. The long-awaited Little Rock, Mississippi River, and Texas Railroad (later known as the Iron Mountain) reached the town in 1880 and provided faster and better long-distance transportation. From 1874 to 1896, Monticello hosted the Southeast Arkansas Fair. People attended from all over southeast Arkansas and northeast Louisiana. The town’s most enduring mercantile store opened in 1881 when John J. McCloy and Virgil J. Trotter Sr. formed McCloy & Trotter Mercantile and Grocery. After McCloy’s death, the business continued as V. J. Trotter & Sons until it was sold in 1970. In 1886, an African-American man named Buck Hunter was lynched in Monticello, while another man, James Jones (also referred to as W. A. Jones), was lynched in 1895. The first bank, Monticello Bank, opened in April 1887 (it would eventually evolve into Union Bank & Trust Company). Also in 1887, Hannah Hyatt began accepting orphans into her home. She donated her home and eighty acres to the State Baptist Convention in 1894, and the institution became the Arkansas Baptist Home for Children, which still exists. Telephone service reached the town in 1898. A cottonseed oil mill opened in 1890.

Early Twentieth Century

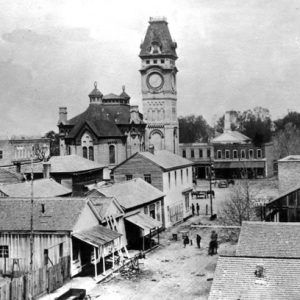

Monticello experienced immense growth in the early twentieth century. The community’s resident architect, Sylvester Clifford Hotchkiss, designed a number of local buildings, some of which were later listed on the National Register of Historic Places. The Monticello Cotton Mill, founded by Warren Anderson, opened in 1900. Two cotton gins, a fertilizer plant, an ice plant, and a canning factory were built in connection with the cottonseed mill during this era. Several new banks formed. Mrs. James Gaston Williamson (née Lula Jackson) organized United Charities, composed of ladies from the town churches, in 1910. United Charities established a nursery for children whose mothers worked at the cotton mill and a home for women who were no longer able to work there. This effort led to the creation of what is now Vera Lloyd Presbyterian Family Services in 1923; it still exists. Martin L. Sigman established a stave mill in 1914. The Sorosis Club, formed in 1902, established the Drew County Library in 1928. The next decade saw more progress. The Mack Wilson Hospital opened in 1930. The same year, Edward Lee Stephenson founded Stephenson’s Funeral Home, now the Stephenson-Dearman Funeral Home. A new courthouse was erected in 1932, and a municipal building was built two years later. A Coca-Cola plant opened in 1935, and a municipal swimming pool opened the next year. Many buildings constructed during this period of growth are part of the Monticello Commercial Historic District.

In 1921, an African-American man was lynched for allegedly assaulting a white woman in nearby Wilmar (Drew County). At the beginning of the Great Depression in 1929, the Drew County Bank & Trust Company closed and was liquidated the following year. The manager, Henry Cruce, committed suicide. Although some businesses closed, the more established ones managed to stay open. The population increased during this decade as many farmers lost their farms and moved to town in search of work.

World War II through the Modern Era

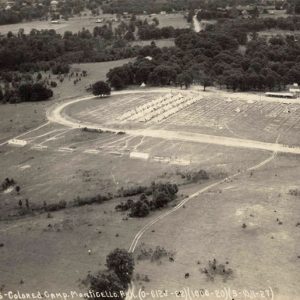

Soon after the outbreak of World War II, the effects of the Depression began to diminish. The Monticello Cotton Mill manufactured a coarse grade of cotton material that was used by the military for tents, cots, and awnings. It ran at full capacity throughout the war and employed many, enticing more rural people to relocate. Camp Monticello was a prisoner-of-war (POW) camp south of Monticello; Italian POWs began arriving in 1943.

Drew Memorial Hospital was built in 1950, and in 1975, a modern building replaced the original. Local resident John Porter Price established the J. P. Price Lumber Company in 1965; it claims to be one of the largest wood-processing companies in the United States. Among the major industries in 1974 were Arvin (automotive exhaust systems manufacturer), L. T. Barnes (pulpwood), Burlington Industries (textiles), the Coca-Cola Bottling Company, Davis Forest Services, Drew Cotton Seed Oil Mill (later Drew Foam), Dura-Craft Boats (now War Eagle Boats), Georgia-Pacific (forestry), MonArk Boat Company (now SeaArk Marine), and Wilson Sawmill. Richard Akin established Akin Industries, manufacturing furniture for healthcare customers, in 1985. The building of a Walmart Supercenter in the 1990s spurred commercial development west of the center of town. Chuck and David Dearman of Dearman Companies established North Park Village Shopping Center next to Walmart Inc. This commercial strip, about two miles long, did not cause the original civic center around the old courthouse town square to languish.

Education

Monticello has always been a center for schools. Rodger’s Female Academy closed during the Civil War and reopened as Wood Thompson School for Boys. The name changed to Thompson High School when it became coeducational. Phi Kappa Sigma Male College was established by an act of the legislature in 1859. It was organized by Professor James William Barrow, who named it after his college fraternity. The Monticello Male Academy and Bessilieu Schoolhouse opened soon after the Civil War. Hinemon University, under the tutorship of John H. Hinemon, was established in 1890. The first public school opened in 1876 for a three-month session, and a nine-month school opened in 1883. The name changed to Monticello High School in 1910. A private school for black students, known as Monticello Academy or Presbyterian School, was established in the late 1890s. A public school for black students opened in the late 1920s. The Fourth District State Agricultural School, commonly called SAS, held its first classes in 1910. The name changed to Arkansas Agricultural and Mechanical College (Arkansas A&M) in 1925, and it received junior college certification in 1928. It reached senior college status in 1939 and was accredited the next year. In 1971, the college became part of the University of Arkansas system and was renamed the University of Arkansas at Monticello (UAM).

Attractions

The Drew County Historical Museum houses impressive artifacts and serves as an archive for southeast Arkansas history. Several grandiose houses on North and South Main streets are on the National Register of Historic Places. Nearby Lake Monticello offers recreation. The historic Monticello Post Office, now home to the Economic Development Commission, is one of nineteen places in Arkansas where Depression-era post office art may be viewed.

Famous Residents

Major General John Shirley Wood, born in 1888, served in both world wars. Hershel Wayne Gober, born in Monticello on December 21, 1936, became the highest-ranking federal government official from southeastern Arkansas. He served in the military for ten years, retiring with the rank of major in 1978. Governor Bill Clinton appointed him to become the Director of Veterans Affairs for Arkansas on January 4, 1988. He also served as a member of the governor’s state cabinet. He resigned on February 4, 1993, to go to Washington DC, where President Clinton appointed him to become deputy secretary of the U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs. In 1997, he served as acting secretary until a new appointment was made and then returned to the deputy secretary position the same year. He became acting secretary again in 2000 and served until January 20, 2001; when serving as acting secretary, he was a member of the cabinet.

For additional information:

DeArmond, Rebecca. Old Times Not Forgotten: A History of Drew County. Little Rock: Rose Publishing Company, 1980.

Leslie, James. Land of Cypress and Pine: More Southeast Arkansas History. Little Rock: Rose Publishing Company, 1976.

Monticello, Arkansas. http://www.monticelloedc.org/ (accessed July 21, 2022).

Rebecca DeArmond-Huskey

Wilmar, Arkansas

A. H. Thomasson and Son Tailors

A. H. Thomasson and Son Tailors  African American Flood Refugees

African American Flood Refugees  Allen House

Allen House  Arkansas Baptist Orphanage

Arkansas Baptist Orphanage  Bottom's Orphange

Bottom's Orphange  Chamberlin Complex

Chamberlin Complex  Drew County Courthouse

Drew County Courthouse  Drew County Courthouse

Drew County Courthouse  Drew County Map

Drew County Map  Drew County Museum and Archives

Drew County Museum and Archives  Hotchkiss House

Hotchkiss House  Lake Monticello

Lake Monticello  Monticello City Scene

Monticello City Scene  Monticello Confederate Monument

Monticello Confederate Monument  Monticello Depot

Monticello Depot  Monticello Downtown Square

Monticello Downtown Square  Monticello Fire Department

Monticello Fire Department  Monticello Post Office

Monticello Post Office  Monticello Postcard

Monticello Postcard  Monticello Street Scene

Monticello Street Scene  Monticello View

Monticello View  Monticellonian

Monticellonian  Charlie May Simon

Charlie May Simon  White Flood Refugees

White Flood Refugees

My grandmother, Jewel Mhoon McGough, had three brothers that owned the Mhoon Brothers Barber Shop downtown for years. The brothers’ names are Herman, Earnest, and Arthur. Arthur eventually left the barbershop to open a jewelry store in Hope. My mother, Lucille McGough Bush, worked at Camp Monticello during WWII.

My father, the late Murray “Skinny” Lowery (Lowrey), was known as the ice man. He worked at Drew Foam along with Buddy Owens when it was East End across the train tracks from Carsons.