calsfoundation@cals.org

West Memphis (Crittenden County)

| Latitude and Longitude: | 35º08’47″N 090º11’04″W |

| Elevation: | 215 feet |

| Area: | 28.84 square miles (2020 Census) |

| Population: | 24,520 (2020 Census) |

| Incorporation Date: | May 7, 1927 |

Historical Population as per the U.S. Census:

|

1810 |

1820 |

1830 |

1840 |

1850 |

1860 |

1870 |

1880 |

1890 |

1900 |

|

– |

– |

– |

– |

– |

– |

– |

– |

– |

– |

|

1910 |

1920 |

1930 |

1940 |

1950 |

1960 |

1970 |

1980 |

1990 |

2000 |

|

– |

– |

895 |

3,369 |

9,112 |

19,374 |

26,070 |

28,138 |

28,259 |

27,666 |

|

2010 |

2020 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

26,245 |

24,520 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

West Memphis is the largest town in Crittenden County. Located on the west bank of the Mississippi River where I-55 and I-40 meet, West Memphis has been referred to as the crossroads or mid-point of the United States and is one of the largest trucking centers in the nation. Memphis, Tennessee, is located just across the Mississippi River.

Pre-European Exploration through European Exploration and Settlement

Native Americans lived in the Mississippi River Valley for at least 10,000 years, although much of the evidence of their presence has been buried or destroyed. The Indians of the Mississippian Period were the last native inhabitants of the West Memphis area. Mound City Road, located within the eastern portion of the West Memphis city limits, has a marker indicating that the villages of Aquixo (Aquijo) or Pacaha were in the area. Several mounds are still visible.

Explorers from both Spain and France visited the area near West Memphis. Among those explorers were Hernando de Soto and his men from Spain and Father Jacques Marquette and Louis Jolliet from France. By the time French hunters and explorers entered the region, the Mississippian towns and other settlements had been abandoned. The original site of West Memphis came from Spanish land grants issued during the 1790s. Grants were given to Benjamin Fooy, John Henry Fooy, and Isaac Fooy in the Hopefield (Crittenden County) area and to William McKenney in the Bridgeport–West Memphis area.

Louisiana Purchase through Reconstruction

Crittenden County was found to yield a variety of plants, especially cotton. With grants given to encourage railroad construction and farming, the county began to prosper. Hopefield was Crittenden County’s first settlement. Benjamin Fooy, who had been sent by the Spanish governor of Louisiana as an Indian agent, established a home site there in 1795. Under his magistrate, Hopefield became known as one of the cleanest places on the river. However, after his death in 1823, the town’s reputation began to decline, and it became a hangout for gamblers and thieves who had been banished from the city of Memphis. A notable duel took place there in February 1845 between a Mr. Clancey of Memphis and a Mr. Thompson of Vicksburg, Mississippi, in which, after both were wounded by bullets, Thompson killed Clancey by stabbing him in the chest.

In 1855, in spite of its rough reputation, Hopefield was chosen as the eastern terminus of the Memphis and Little Rock Railroad. In 1858, Irish immigrants helped provide labor that connected the first railroad in Arkansas from Memphis, Tennessee, to Madison (St. Francis County). In 1861, with the beginning of the Civil War, construction of the railroad was halted, and the shops at Hopefield were turned into an armory for the Confederacy. Farming had to be discontinued due to able-bodied men enlisting.

Construction and funding of the railroads resumed in 1867. On April 11, 1871, the Memphis and Little Rock Railroad was completed. Following the Civil War, the saloons, pool halls, cockfights, boxing matches, and horse racing caused Hopefield to be labeled as a rollicking and booming town. Some settlers left the area to build behind the levee.

Post Reconstruction through the Gilded Age

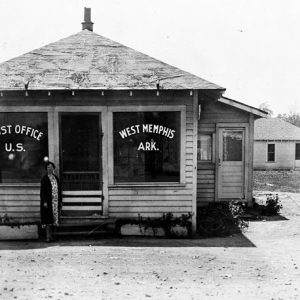

The first buildings on the banks of the Mississippi River were a residence, built in 1875, and the railroad station. Both were built on stilts to keep out the floodwaters. In 1884, a town was laid out, and with a population of 200, West Memphis appointed its first postmaster, Robert Vance. The early West Memphis site had a grain elevator, a two-story hotel, two sawmills, and several boarding houses. Due to the change from river traffic to rail traffic and the introduction of lumbering in the area, people began to drift toward the new West Memphis.

The West Memphis area usually flooded in the spring until the St. Francis Levee District was established in 1893. However, private landowners along the Mississippi River built levees that were only three or four feet high. In 1912 and 1913, the St. Francis main levee broke, flooding the area from West Memphis to Forrest City (St. Francis County); Hopefield was washed away in 1912. The current was so strong that steel rails wrapped around trees. During the Flood of 1927, another break in the levee left the area under water, and during the Flood of 1937, the river washed over the top of the levees. However, less damage was done than in 1913. After the levees were built to help with the floodwater, people saw the need for a town government.

Early Twentieth Century

Both the building of the railroads and the clearing of the timberlands helped establish the second West Memphis. It was located near the area that is about three miles south of the present town’s 8th through 12th streets. General George Nettleton, an official of the Kansas City, Fort Scott and Memphis Railroad, known today as the Burlington Northern Railroad, named the town West Memphis in 1883. The surrounding land was filled with virgin timber.

In the early 1900s, Henry Ruple Dabbs and his brother Ed established their general store in a building in Hulbert, an area that was later annexed by West Memphis. This was once called Berkley’s Landing. Their business was in the two-story brick building at 1320 South Avalon, which is now on the National Register of Historic Places. Until the post office at the second West Memphis was established in 1920, patrons received their mail through the Hulbert office by a horseback rider.

The first river bridge opened on May 12, 1892. A second bridge, known as the Harahan Bridge, was built across the Mississippi River and opened in 1916. Before it was built, most vehicles, except trains, had to ferry across the Mississippi River. Tolls were collected to help pay for the bridge until 1930. The Harahan Bridge was damaged by fire in 1928, and it reopened after eighteen months of repairs.

In 1927, West Memphis was incorporated. The first mayor was Zach T. Bragg, who established one of the first logging mills in the region. The elementary school located at 309 W. Barton Avenue is named Bragg Elementary in honor of him.

World War II through the Modern Era

In the 1930s, 1940s, and 1950s, 8th Street was often called “Beale Street West,” reflecting a music and nightlife scene to equal that in Memphis. Some places in West Memphis have been associated with famous entertainers, such as the Square Deal Café—referred to as Miss Annie’s Place on South 16th Street, where B. B. King began his public entertaining—and The Coffee Cup—located at 204 East Broadway in the 1950s, outside which Elvis Presley ate his first breakfast after being inducted into the U.S. Army on March 24, 1958. Other popular night spots along Broadway Street were Willowdale Inn, the Cotton Club, and the supper club known as the Plantation Inn.

Legal greyhound racing began in the county in 1935. In the years that followed, the track closed several times—once for flooding, another due to the nation’s involvement in World War II, and another time due to fire. However, the business currently known as Southland Park Gaming & Racing and located on North Ingram Boulevard has been in the same location since 1956 and is now open every day of the week, including twenty-four hours on weekends.

West Memphis began its role as a trucking hub with the opening of parts of I-55 in the 1950s. With both I-55 and I-40 traveling toward the Mississippi River, West Memphis became known as the crossroads of America in the trucking industry. In 1972, a six-lane highway bridge, known as the Hernando de Soto Bridge and located north of the Harahan, opened as part of I-40.

On December 14, 1987, a tornado killed six people and caused approximately $35 million in damage. The town had not recovered from the tornado damage when it flooded from twelve inches of rain on December 25, 1987. In addition to that, seven to ten inches of snow fell on January 6, 1988. When the snow began to melt, this added to the already existing flood problems and the destruction caused by the tornado.

On May 6, 1993, the bodies of eight-year-old Michael Moore, Chris Byers, and Stevie Branch were discovered submerged in a drainage ditch a few blocks from their homes. Their hands and feet were bound, their skulls bludgeoned, and they had been sexually mutilated. Police arrested Damien Echols, Jason Baldwin, and Jessie Misskelley for what have become known as the Robin Hood Hills Murders, and all three were convicted in 1994; however, continuing controversies over the case against the “West Memphis Three,” as the defendants have become known, have kept the murders in the national spotlight. In August 2011, the three men were released from prison after they used a rare legal maneuver known as an Alford plea; this allowed them to plead guilty to murder while at the same time maintaining their innocence.

The Crittenden Regional Hospital in West Memphis closed in 2014. The building stood empty for about two years as various plans were put forward regarding its use, until, in 2016, it was leased to the state as a correctional facility for non-violent female felons. On October 22, 2016, Big River Crossing project was opened, which resulted in the Harahan Bridge becoming the longest pedestrian bridge across the Mississippi River and the nation’s largest active rail/bicycle/pedestrian bridge.

Some of the major employers in the city are Schneider National Carriers, Southland Park Gaming & Racing, Family Dollar Distribution, FedEx National LTL, and Robert Bosch Power Tools. Family Dollar Distribution and FedEx National LTL are located in the Mid-America Industrial Park west of the city.

Education

West Memphis has one public school district with an enrollment of almost 6,000 students. The district includes eight elementary schools, three junior high schools, and one high school. The town also has two private schools—West Memphis Christian School, which is pre-school through twelfth grade, and St. Michael’s School, which is pre-school through sixth grade.

After the Brown v. Board of Education decision, the West Memphis School District began the desegregation process. In the 1955–1956 school term, the district established attendance zones. In 1960, busing was halted. In 1965, the school district adopted a Freedom of Choice plan of gradual integration. Later that year, a group of African Americans filed a complaint in the United States District Court protesting this plan. As a result of the litigation, Federal Judge Thomas Eisele issued an order on February 3, 1971, for all schools to be integrated no later than October 11, 1971, with each school maintaining a thirty percent minority status. The integration process began at the start of the 1966–1967 term and was achieved at the start of the 1971–1972 term.

Mid-South Community College changed from a vocational technical school to a community college in 1993. The two-year public institution offers associate degrees and partners with several four-year institutions of the state in various areas of study.

Attractions and Notable Figures

Some major events held in the city are Gumbo Fest in April, Taste of the Town in August, Blues in the Park during the summer, Main Street Fall Festival in September or October, Chamber of Commerce Business Expo in September, and the Carriage Rides and Christmas Tree Lighting in November/December. In 1990, a non-profit organization called Main Street West Memphis began revitalizing fifteen blocks of Broadway Avenue, the major street of the city. In July 2008, the 700, 800, and 900 blocks of Broadway were designated as a Commercial Historical District on the National Register of Historic Places. “Big John” Tate, born in West Memphis, gained notoriety as a successful amateur and professional boxer. Scenes from the movie Hallelujah (1929) were filmed near West Memphis, making it one of Hollywood’s earliest feature films to be shot in Arkansas.

For additional information:

Claiborne, Taylor, ed. West Memphis, 1927–1976. West Memphis, AR: Printing Crafts Inc., 1976.

The Crittenden County Rambler: Guide to Historic Places. West Memphis, AR: Crittenden County Historical Society, 1983.

Hosken, Simon Rosewall. “Conversations with West Memphis: A Sense of Place and Heritage.” PhD diss., Arkansas State University, 2011.

———. “Policing the Blues: Remembering the Desegregation of Law Enforcement in West Memphis, Arkansas.” Arkansas Historical Quarterly 72 (Summer 2013): 120–138.

Neill, Kenneth. “Truckstop City, Razorback to the Core: West Memphis Is Itching to Boom.” Arkansas Times, August 1979, pp. 30–41.

Nelson, Rex. “Boom Town.” Arkansas Democrat-Gazette, February 9, 2020, pp. 1H, 6H.

Vickers, Norman C. A Historical Survey of Crittenden County, Arkansas. Earle, AR: The Crittenden County Arkansas Museum, 2006.

West Memphis Chamber of Commerce. http://www.westmemphischamber.net/ (accessed September 30, 2022).

Woolfolk, Margaret Elizabeth. A History of Crittenden County Arkansas. Greenville, SC: Southern Historical Press, 1993.

Charlotte C. Wicks

Marion, Arkansas

The Coffee Cup

The Coffee Cup  Cotton Wagons

Cotton Wagons  Cottonseed Oil Mill

Cottonseed Oil Mill  Crittenden County Map

Crittenden County Map  Greyhound Racing

Greyhound Racing  Hernando de Soto Bridge

Hernando de Soto Bridge  Highway 70 Bridge

Highway 70 Bridge  "Moanin' at Midnight," Performed by "Howlin' Wolf"

"Moanin' at Midnight," Performed by "Howlin' Wolf"  St. Michael's School

St. Michael's School  West Memphis Train Station

West Memphis Train Station  West Memphis Post Office

West Memphis Post Office  West Memphis

West Memphis  West Memphis, 1930

West Memphis, 1930  West Memphis; 1935

West Memphis; 1935  West Memphis Flood

West Memphis Flood  West Memphis Street Scene

West Memphis Street Scene

Comments

No comments on this entry yet.