calsfoundation@cals.org

Big Lake Wars

Competition and contention over an abundant (and unregulated) storehouse of northeastern Arkansas wildlife from the mid-1870s until 1915 led to violence and controversy known as the Big Lake Wars. Big Lake refers to a section of western Mississippi County created by the massive New Madrid Earthquakes of 1811–1812. “War” may be a misleading description of the events because there were no formalities, declarations, truces, or settlements. However, the conflict had a lasting impact on the state and even on the nation. The Big Lake Wars pitted local residents, who were mostly poor, against affluent northerners, chiefly from St. Louis, Missouri.

Early Arkansas maps labeled the sparsely populated area between Crowley’s Ridge and the Mississippi River as “the Great Swamp.” After the Civil War, the railroad boom included the building of the St. Louis, Iron Mountain and Southern Railway from St. Louis to Texarkana (Miller County), as well as the construction of the St. Louis–San Francisco Railway (Frisco). Both railroads built branch lines in northeastern Arkansas to haul timber from the vast hardwood forests to meet the building needs of the nation.

The post–Civil War period also spawned hunting excursions as a pastime for the well-to-do. Groups, some formed into hunting clubs, chartered railroad cars to travel to the Big Lake area for extended hunts in a time when there were no regulations, state or federal, on the taking of wild game.

The trains that took out timber also provided transportation for the products of the market hunters—mostly deer, ducks, and fish. Subsistence hunting, food for tables, became overshadowed by hunting that brought in money. Restaurants north of Arkansas often featured wild game from the Big Lake area, and iced barrels of venison, ducks, fish, and even frogs went aboard the trains in the area and headed north. The fish were usually largemouth bass and crappie, as catfish were disdained at that time.

Friction quickly arose between the local hunters and the visiting sportsmen, both using the same timberland lowland area. The St. Louis people began leasing land to keep out other hunters, and disputes flared into fights, shootings, and beatings. Some clubhouses and lodges, which were constructed with the readily available hardwood lumber, were burned.

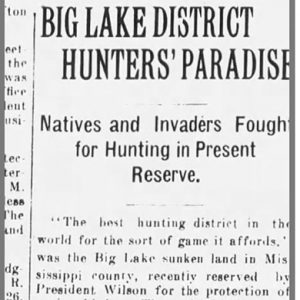

Local residents regarded the watery Big Lake country as theirs to hunt. Clubs signed leases and bought land, and lumber companies bought the timber rights. Titles to the land, however, were sometimes questionable if not fraudulent. Numerous court actions resulted. An avalanche of local legislation came out of the Arkansas General Assembly but was largely ineffective. Some of the laws prohibited out-of-state residents from hunting in Arkansas, and the wealthy sportsmen often paid the fines and went on hunting.

At the beginning of the twentieth century, concerns over dwindling wildlife populations emerged on a national level as well as in Arkansas. The international Migratory Bird Treaty was passed by Congress in 1913, putting ducks and geese under federal control. New federal and state laws were passed to establish hunting seasons and, later, to set daily limits on the taking of wildlife.

Big Lake National Wildlife Refuge, the first such refuge in Arkansas, was established in 1915, and the Arkansas Game and Fish Commission (AGFC) was created, also in 1915. The prime mover behind the formation of the AGFC was state senator Junius Marion Futrell of Paragould (Greene County), which is near Big Lake; Futrell later became governor. Arkansas’s governor in 1915, George Washington Hays, pitched his support behind Futrell’s legislation to get it passed and signed into law. The new agency had a staff of nine part-time game wardens to patrol the entire state, and one was a Paragould resident. These agencies, refuges, and regulations helped bring the four decades of conflict to a close.

Not directly tied to the Big Lake situation was the arrival of rice farming in the Grand Prairie region of Arkansas. Migrating ducks made seasonal use of the farms’ man-made reservoirs in addition to the nearby bottomland hardwood areas, and Stuttgart (Arkansas County) became a center of duck hunting. But the wintering ducks did not forsake Big Lake. To aid in their management, the AGFC in the early 1950s created Big Lake Wildlife Management Area on the eastern side of Big Lake National Wildlife Refuge, along with St. Francis Sunken Lands Wildlife Management area just to the west and southwest. A 1980s report by the federal refuge’s manager estimated that one million ducks were on the refuge in an early December survey.

For additional information:

Capooth, Wayne. The Golden Age of Waterfowling. N.p.: 2001.

Morrow, Lynn. “Duck and Goose Shambles: Sportsmen and Market Hunters at Big Lake, Arkansas.” Big Muddy: A Journal of the Mississippi River Valley 4, no. 1 (2004). Online at http://www.semopress.com/a-duck-and-goose-shambles-sportsmen-and-market-hunters-at-big-lake-arkansas/ (accessed November 4, 2021).

Sutton, Keith, ed. Arkansas Wildlife: A History. Fayetteville: University of Arkansas Press, 1998.

Wright, Steve, and Steve Bowman. Arkansas Duck Hunters Almanac. Fayetteville, AR: Ozark Delta Press, 1998.

Joe Mosby

Conway, Arkansas

Early Twentieth Century, 1901 through 1940

Early Twentieth Century, 1901 through 1940 Politics and Government

Politics and Government Recreation and Sports

Recreation and Sports Big Lake Article

Big Lake Article

Comments

No comments on this entry yet.