calsfoundation@cals.org

Worms [Medical Condition], Traditional Remedies

aka: Intestinal Parasites

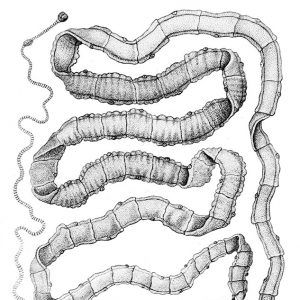

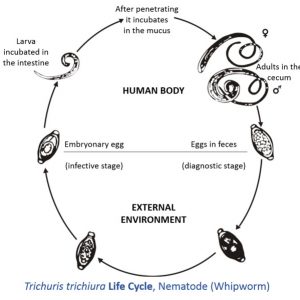

Well into the twentieth century, it was believed that all children had parasitic worms and that parents needed to treat this condition with patent or homemade medicines. These concoctions rid children of such intestinal parasites as roundworms (Ascariasis), threadworms (Trichuris), and tapeworms (Taenia solium), some of which also went by the colloquial names of pinworms and seatworms. Worm infestations, it was believed, could cause death.

This is borne out by the census’s four mortality schedules (1850–1880). In these, “worms” and “worm fever” were listed as the causes of some children’s deaths, the majority occurring during the warm months of July through October. Some of these children may have died from the debilitating effects of worms or by being overdosed with vermifuge (an agent that works to expel or destroy intestinal parasites). However, in the case of one- and two-year-olds, the more likely cause was the change in diet occasioned by teething and beginning solid foods, during months when that food was most susceptible to spoilage. (This is also true for those deaths believed to have been from teething.)

Intestinal parasites were the direct result of poor sanitation (especially the lack of, or refusal to use, outdoor toilets). It was commonly believed, however, that children acquired worms by eating dirt, a practice associated with the South known as geophagy. This desire to eat “clay dirt” or chalk was first observed among slaves during colonial times, and later among both black and white women (especially pregnant women) and children. The craving to eat dirt is believed to be caused by a dietary deficiency. Doing so was not without risk; Mary Towson, a seven-year-old African American, is listed on the 1880 mortality schedule (Drew County) as having died from “eating dirt.” The practice, which continues to this day, does not cause worms, and may even be a symptom of parasite infection rather than a cause.

Patent medicine advertising and the popular self-help medical books of the day gave long lists of often conflicting symptoms to diagnose the presence of worms. These included teeth grinding and restless sleep, irritability, an off-color complexion (yellow, pasty, pale, or having red cheeks and a white mouth), colic pain, bad breath, flatulence, and/or itching of the nostrils or rectum. Other signs were emaciation and a voracious appetite or disgust at seeing food.

A number of herbal and folk remedies were used to expel worms. The most oft-cited was making molasses candy and adding Jerusalem Oak (Chenopodium botrys), colloquially known as wormseed, goosefoot, or American wormseed. (Chenopodium was one of two deworming medicines dispensed by the Rockefeller Sanitary Commission between 1910 and 1914 in an effort to eradicate hookworms.) Other home cures included making teas from pumpkin seeds, peach leaves, wild sage, rue, horsemint, senna, homegrown tobacco, or pokeroot, all readily available in Arkansas.

In keeping with the Southern belief in the medicinal properties of turpentine, some parents fed their children sugar laced with drops of turpentine, or rubbed the child’s navel and throat with the liquid, believing that this rid the body of worms. African Americans in the Mississippi River Delta in the 1970s reported dosing children with coal oil, copperas (also used to deworm hogs), and calamus (Acorus calamus), a root used by whites, as well.

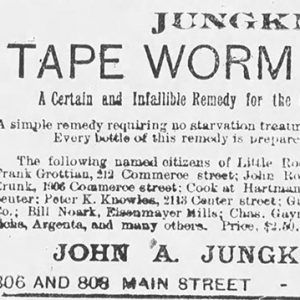

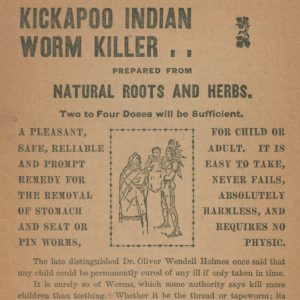

Those who could afford to purchase over-the-counter or patent medicines had numerous, heavily advertised brands to choose among. These included the ever-popular Black Draught (also a laxative), White’s Cream Vermifuge, Jayne’s Vermifuge, Jungkind’s Tape Worm Specific, and Kickapoo Worm Killer, all of which advertised extensively in Arkansas newspapers.

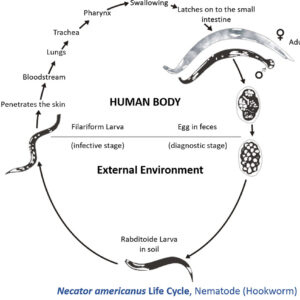

One type of worm infestation, hookworm (Necator americanus), was successfully combated in Arkansas by the Rockefeller Sanitary Commission from 1910 to 1914. In order to diagnosis this condition, people were required to bring stool samples to be tested, and patients were treated for all intestinal worms found in the samples. Still, most parents continued to give their children a precautionary dose of vermifuge on at least a yearly basis. In twenty-first-century Arkansas, intestinal parasites are not widespread (but not uncommon, especially among young children) and are treated successfully with prescription medications.

For additional information:

Frate, Dennis A. “Dirt Eating (Geophagy).” In Encyclopedia of Southern Culture, edited by Charles Reagan Wilson and William Ferris. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 1989.

Fravel, Jesse. “The Arkansas Hookworm Eradication Program of 1910–1914.” Faulkner Facts and Fiddlings 12 (Winter 1970): 91–95.

———. “The Hookworm Doctor.” Rivers and Roads and Points in Between 2 (Spring 1974): 34–36.

Morson, Donald, Frank Reuter, and Wayne Viitanen. “Negro Folk Remedies Collected in Eudora, Arkansas, 1974–1975.” Mid-South Folklore 4 (Spring 1976): 11–24.

Randolph, Vance. Ozark Magic and Folklore. New York: Dover Publications, Inc., 1964.

Vaughn, Freddie, and Frank Reuter. “Negro Folk Remedies Collected in Southeast Arkansas, 1976.” Mid-South Folklore 4 (Summer 1976): 61–73.

Abby Burnett

Kingston, Arkansas

Early Twentieth Century, 1901 through 1940

Early Twentieth Century, 1901 through 1940 Nematodes

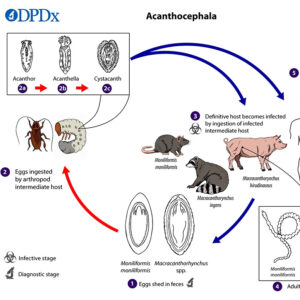

Nematodes Acanthocephala Life Cycle

Acanthocephala Life Cycle  Hookworm Larva

Hookworm Larva  Hookworm Life Cycle

Hookworm Life Cycle  Hookworms in the Intestine

Hookworms in the Intestine  Roundworm

Roundworm  Tapeworm

Tapeworm  Trichuris Life Cycle

Trichuris Life Cycle  Wickliffe Rose

Wickliffe Rose  Worm Cure Ad

Worm Cure Ad  Worm Killer Ad

Worm Killer Ad

Being from the poor side of the Blue Ridge Mountains, I recall in about 1949 my mother using kerosene on a bad cut on my left foot to secure the bleeding. Never heard of that folk remedy before, until reading it here.

I grew up in southern Missouri. I am now seventy-six. Two to three times each year, my mom dosed me with one teaspoon of sugar containing a single drop of kerosene to kill my intestinal worms. I don’t recall any ill effects.