calsfoundation@cals.org

Pulaski Light Artillery Battery (CS)

aka: Totten Artillery Company

While Arkansas militia laws in the antebellum period authorized the formation of four militia companies of artillery, cavalry, infantry, and light infantry in each county, few such organizations existed. Pulaski County was an exception to this, and in the years before Arkansas’s secession, there were four volunteer militia units there, including the Totten Artillery, later renamed the Pulaski Light Artillery. While their service was brief compared to other Arkansas units during the Civil War, the men of the Pulaski Light Artillery played a pivotal role in the Battle of Wilson’s Creek, Missouri, on August 10, 1861.

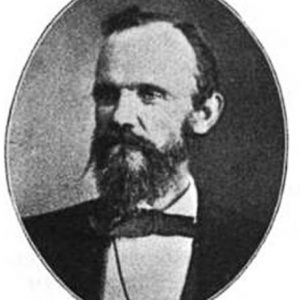

On February 14, 1861, Captain William C. Woodruff composed a letter to Colonel Craven Payton of the Thirteenth Regiment, Arkansas State Militia, informing him of the raising of the “Totten Artillery Company” in Little Rock (Pulaski County), as well as requesting that Col. Payton “make a requisition on the governor of Arkansas for sufficient arms to equip said company say for: 15 mini[é] rifles, one battery consisting of three 6-pounder cannon and one 12-pounder howitzer, site [sic] arms for 50 officers and men under the Act of Assembly approved January 20, 1861.” Woodruff, a graduate of the Western Military Institute in Georgetown, Kentucky, was the son of William E. Woodruff, founder of the Arkansas Gazette and an early settler in Arkansas Territory. Returning to Little Rock in 1859, Woodruff studied the law and then opened his own practice. With his education and social standing, Woodruff was elected as captain of the new artillery battery, named for local physician Dr. William Totten and his son, Captain James Totten, Battery F, Second United States Artillery Regiment, who was stationed at the Little Rock Arsenal. Capt. Totten assisted Woodruff in the training of his men in artillery drill.

In January 1861, rumors arrived via telegraph of the reinforcement of the arsenal’s garrison, which inflamed pro-secessionist feelings in the state. Governor Henry Rector sent a letter to Capt. Totten asking him to confirm the rumors and declare his intentions; Totten responded by stating that he had no knowledge of reinforcements and that as a soldier of the U.S. Regular Army, while his duty was to follow orders, he was personally committed to avoiding “collision between the Federal troops under my command and the citizens of Arkansas.”

With the news of reinforcements, Arkansas’s militia sprang to action, with 5,000 volunteers arriving at Little Rock by early February 1861. With increased tensions and the possibility of a preemptive attack on the arsenal, Gov. Rector implored Totten to surrender his garrison. Totten, not wishing to be the cause of possible bloodshed, agreed to the demand, provided the governor arranged for safe conduct for his men. On February 8, Totten was formally escorted from the garrison. He and his men made their way to the Federal Arsenal in St. Louis, Missouri. A committee of the Ladies of Little Rock, in appreciation of Totten’s foresight, presented him with a sword, with the inscription: “When woman suffers, chivalry forbears; the soldier fears all danger but his own.”

In late April 1861, the Totten Artillery (soon to be renamed the Pulaski Light Artillery) was ordered to Fort Smith (Sebastian County), joining Colonel Solon Borland and other forces in securing that federal post for the South. After serving briefly in abandoned Fort Smith, the battery returned to Little Rock.

In late May, the unit was ordered to return to Fort Smith. Before the men boarded the steamboat Tahlequahon May 23, clad in new uniforms of gray jeans-wool and red trim made by the ladies of Little Rock, the battery was presented a flag by Miss Juliet Langtree. Langtree gave a spirited and emotional charge to the men that “those you leave behind you will drop a tear for the soldier and offer up a prayer for his safety.”

On June 18, the battery was ordered to move to Van Buren (Crawford County). Shortly afterward, it marched to Camp Walker, in Benton County, where the unit came under command of General Nicholas B. Pearce of the Arkansas State Troops. The battery spent the summer of 1861 drilling. While at Fort Smith, Woodruff noted that he had to observe the artillery drill of Captain John Reid’s Fort Smith Battery on several occasions to refresh his memory.

General Nicholas B. Pearce, commander of Arkansas State Troops, and General Sterling Price, commander of the Missouri State Guard, agreed to place their commands under the overall command of General Benjamin McCulloch. In August, Gen. McCulloch ordered his command, including the Pulaski Light Artillery, to advance into southwestern Missouri, where the army went into camp along the banks of Wilson’s Creek, near the Telegraph Road, which ran between Fayetteville (Washington County) and Springfield, Missouri. McCulloch’s plan was to attack 5,000 Federal soldiers under the command of Brigadier General Nathaniel Lyon near Springfield. Plans were made for a night march on the evening of August 9 to Springfield, but McCulloch countermanded his order due to a sudden rain storm. Gen. Lyon, in the meantime, had ordered his command to march from Springfield in an attack of his own, which was supposed to stun the Southerners and allow him to retreat to Rolla, Missouri, about 100 miles northeast of Springfield. In the early morning hours of August 10, Lyon achieved the element of surprise and launched an attack on the Southern camps, who did not post sentries after their own advance was canceled.

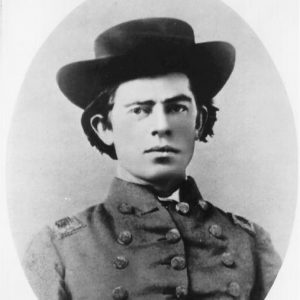

The battery soon found itself under fire from Lyon’s forces, and Captain Woodruff, without direct orders, began to return fire, checking Lyon’s advance across the slopes of Oak Hill (later known as “Bloody Hill”) toward the Confederate encampments. Woodruff’s efforts bought Price and McCulloch time to reorganize their forces to meet Lyon’s onslaught. Woodruff frequently found himself engaging in counterbattery fire with Dubois Battery, on the left of the Union battle line, and Battery F, Second United States Artillery, commanded by Capt. Totten, their old instructor from the Little Rock Arsenal. The battery’s conspicuous role in checking Lyon’s advance made it a target for a battalion of the First U.S. Infantry under the command of Captain Joseph Plummer, who had been ordered by Lyon to cross to the east side of Wilson Creek in a flanking maneuver. Before Capt. Plummer and his men could reach the battery, they were repulsed by the Third Louisiana and Second Arkansas Mounted Rifles, led by Colonel James McIntosh. During this counter-battery fire, Lieutenant Omer Rose Weaver was mortally wounded when a solid shot struck him in the right shoulder.

After the Battle of Wilson’s Creek, McCulloch ordered his command to return to Arkansas, while Price’s Missouri State Guard advanced toward the Missouri River. In late August, at Camp Walker, the Arkansas state forces were given the choice of remaining in state service or enlisting in the Confederate army. The battery voted to remain with the state and was sent to Fayetteville in early September 1861 to be mustered out of service, and the battery’s guns and other property were turned over to Confederate authorities.

In December 1861, Woodruff organized another battery named the “Weaver Light Artillery,” with about thirty veterans of the Pulaski Light Artillery enlisting to serve with their old commander. During the remainder of the war, the battery saw a number of consolidations with other artillery units, and served at the battles of Prairie Grove (as Marshall’s Battery), Helena, Bayou Fourche, Prairie D’Ane, Jenkins’ Ferry, Poison Spring, Marks’ Mills, and Pilot Knob, Missouri, before surrendering to Federal forces in May 1865.

For additional information:

Burgess, Stephen. “Lt. Omer Weaver’s Arkansas Belt Plate.” North South Trader’s Civil War Magazine (January 1995): 48–52.

Daniel, Larry J. Cannoners in Gray: The Field Artillery of the Army of Tennessee, 1861–1865. Tuscaloosa: University of Alabama Press, 1984.

Dedmondt, Glenn. The Flags of Civil War Arkansas. Gretna: Pelican Publishing Company, 2009.

Piston, William Garrett. “‘When the Arks. boys goes by they take the rags off the bush’: Arkansans in the Wilson’s Creek Campaign of 1861.” In The Die Is Cast: Arkansas Goes to War, 1861, edited by Mark K. Christ. Little Rock: Butler Center Books, 2010.

Piston, William Garrett, and Richard W. Hatcher. Wilson’s Creek: The Second Major Battle of the Civil War and the Men Who Fought It. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2001.

Todd, Frederick P. American Military Equipage, 1851–1872: A Description by Word and Picture of What the American Soldier, Sailor, and Marine of These Years Wore and Carried, with Emphasis on the American Civil War. New York: Scribner, 1980.

Woodruff, William E. With the Light Guns in ’61–’65. Little Rock: Central Printing Company, 1903.

Woodruff’s Battery Information File. John K. and Ruth Hulston Civil War Research Library, Wilson’s Creek National Battlefield, Republic, Missouri.

Todd Wilkinson

Ozarks Technical Community College

Civil War Timeline

Civil War Timeline Military

Military Robert C. Newton

Robert C. Newton  Pulaski Battery Site

Pulaski Battery Site  Omer Rose Weaver

Omer Rose Weaver

Comments

No comments on this entry yet.