calsfoundation@cals.org

Carnegie Libraries

Four libraries built in Arkansas between 1906 and 1915 using grants from philanthropist Andrew Carnegie carry the classification “Carnegie Libraries.” These four libraries were built in Eureka Springs (Carroll County), Fort Smith (Sebastian County), Little Rock (Pulaski County), and Morrilton (Conway County). Of these, two continue to operate as libraries (Eureka Springs and Morrilton), one has been dismantled (Little Rock), and one is being used for a new purpose (Fort Smith).

It is not known how many Arkansas cities applied for grants from Andrew Carnegie, or how many requests were denied, although very few communities nationally were denied grants. One exception was Branch Normal College (now the University of Arkansas at Pine Bluff). Principal Isaac Fisher solicited library funds from Carnegie in 1902 but was turned down.

Andrew Carnegie, born on November 25, 1835, in Scotland, was the son of hand-loom weavers who immigrated in 1848 to the United States. Settling in Allegheny City across the river from Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania, Carnegie replicated the pattern of his parents by working in local textile mills at a young age and, over time, amassed great wealth as an industrialist. After the turn of the century, he sold his steel business interests for $480 million, permitting him to practice a great deal of philanthropy. By the time of his death in 1919, Carnegie had given away some $350 million of his wealth through multiple avenues, of which his flagship was the Carnegie Corporation. In his autobiography, Carnegie recalled how, as a young boy, he enjoyed the free access to the personal library of businessman and iron manufacturer Colonel James Anderson: “It was from my own early experience that I decided there was no use to which money could be applied so productive of good to boys and girls who have good within them and ability and ambition to develop it, as the founding of a public library in a community which is willing to support it as a municipal institution. I am sure that the future of those libraries I have been privileged to found will prove the correctness of this opinion.” Publicity in 1901 surrounding Carnegie’s gift of $5.2 million in U.S. Steel bonds to New York City for the purpose of building sixty-five branch libraries received so much attention that requests from other hamlets began an onslaught of library appeals. Eventually, James Bertram, Carnegie’s secretary, was directed to come up with a plan to address these requests. Bertram labeled his application document a “Schedule of Questions,” requiring communities to submit applications for a library grant addressing four areas: 1) demonstrating a need; 2) providing a location; 3) providing ten percent (based on grant amount) annually for its support (nicknamed “The Carnegie Formula”); and 4) making the library free to all. Money supplied by Carnegie was typically based on U.S. Census figures at around two dollars a person, and local politicians had to be willing to use taxation in support of the library. Using the Carnegie name was not a prerequisite, although roughly a third did. Once approved, cities were notified as to their grant level and directed to start construction with Carnegie financial officer Robert Franks to honor project demands—not in lump sum but gradually.

Although the local community selected the building design, by 1908 Bertram started to steer grantees toward architectural styles using a pamphlet titled Notes on Library Bildings [sic] designating minimum standards and providing six model floor plans. Typically, a staircase led users to a conspicuous center doorway accompanied by a lamppost out front—both features serving as symbols to learning’s elevation and enlightenment. A community not meeting Bertram’s suggested pattern customarily needed to adapt in order to get construction approval. A mainstream design crafted patron space as the main interest, causing a fundamental change in the way libraries had operated. Under the Carnegie floor plan, patrons freely browsed books on open shelves. Previously, patrons directed a library clerk to retrieve books from closed shelves.

The first Carnegie library built in the United States was in 1889 in Braddock, Pennsylvania, while the last was finished in 1946. Worldwide, 2,811 libraries were funded by Carnegie between 1883 and 1946 at a cost of around $56 million; of these, 1,946 were built in the United States from 1,419 grants totaling $41 million, with Indiana receiving the most at 160 buildings. More than half of the libraries built through Carnegie funds are still in operation in the twenty-first century, with two of the four constructed in Arkansas included in that total and both listed on the National Register of Historic Places.

Before any Arkansas community could qualify for a Carnegie grant, the Arkansas General Assembly passed legislation in 1903 authorizing first- and second-class cities to levy and collect ¼ mill on real and personal property, followed the next year with authorization to levy and collect taxes for library purposes.

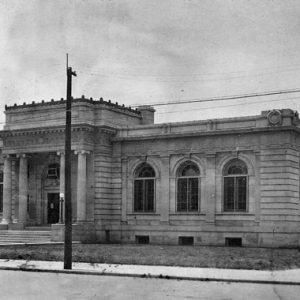

The Carnegie City Library at Fort Smith received a grant of $25,000 on March 24, 1906, after the women’s Fortnightly Club and the Fort Smith Reading Room Association formed the Fort Smith Public Library Association to obtain the grant. The land selected, 318 North 13th Street, had been the site of the home where Judge Isaac Parker died (1895) but had been destroyed by a cyclone in 1898. City Ordinance 709, passed in 1906, allowed for a public library and board of regents to administer it. The cornerstone, complete with time capsule, was laid by contractor W. F. May Company on March 27, 1907, at 3:30 p.m. Using an architectural design shadowing the Guthrie Carnegie Library built in 1901–1903 in Indian Territory (present-day Oklahoma) under architect J. H. Bennett, the Fort Smith library was the first Carnegie Library opened in Arkansas (January 1, 1908) and was formally dedicated on January 30, 1908. This location operated until September 8, 1970, when a new library opened at 61 South 8th Street with formal dedication on November 13. The original Carnegie City Library was sold to the American Television studios, where it later served as part of the KFSM-TV station. In 2001, a newer library opened on Rogers Avenue, and the name was changed to the Fort Smith Public Library.

The Carnegie Library at Little Rock received a grant of $50,000 on March 24, 1906. It was increased to $88,100 on August 6, 1907. Designed by New York architect Edward Tilton (who is credited with more than 100 libraries designed in the United States and Canada, including many Carnegie libraries), the building’s construction started on December 28, 1907, under the direction of local architect Charles Thompson at the southwest corner of West 7th Street and South Louisiana. Opening on February 1, 1910, this library became the foundation upon which the Central Arkansas Library System (CALS) was built. The original Carnegie building was razed in 1964, but some of the original Carnegie furniture is still in use. Furthermore, the four stone columns that graced the front of the original building, saved by Carl Martin, became part of the landscape of the Main Library of CALS in 2009.

The Carnegie Public Library, also known as the Free Public Library, at Eureka Springs received a grant of $12,500 on April 23, 1906, with an increase of $3,000 after Library Board of Trustees president B. J. Rosewater pleaded with Carnegie for extra funding needed to finish construction. Construction was under the direction of contractor Charles W. Conner, taking place at 198 Spring Street starting in 1910 and finishing in 1912. The 3,500-square-foot structure has two stone staircases leading to the front door. The limestone building sits on land donated by R. C. Kerens and was designed by architect George W. Hellmuth of St. Louis, Missouri. The library closed for lack of funding in the winter of 1916, eventually reopening in 1920. Additional levels were added in 1977 and 1989 to provide more shelf room. In 2009, the library reported a collection of 34,695 books and seven computers with free Internet access.

The Carnegie Library at Morrilton, known as the Conway County Library, received a grant of $10,000 on September 29, 1915, with construction taking place at 101 West Church Street and completed in October 1916. The Pathfinder Club, a women’s organization established in 1897, was the driving force behind securing the grant to establish a library. Purchasing a lot downtown for its location, they used books from the library they had started among themselves. The 3,628-square-foot building cost around $7,500, with the remainder for furnishings. Here again the architectural style consists of a stairway leading to a dominant front door between large pillars. Morrilton achieved the distinction of being the smallest town in America to have a Carnegie library at the time of its opening, and the library gained National Register of Historic Places status on April 15, 1978. A new addition was completed in 2000, but the original Carnegie building is still in use as of 2011.

For additional information:

Bobinski, George S. Carnegie Libraries: Their History and Impact on American Public Library Development. Chicago: American Library Association, 1969.

Carnegie, Andrew. Autobiography of Andrew Carnegie. London: Constable and Co., 1920.

Fort Smith Public Library. http://www.fortsmithlibrary.org/ (accessed February 7, 2022).

Herndon, Dallas T. Centennial History of Arkansas. Chicago, S. J. Clarke Publishing Co., 1922.

Jones, Theodore. Carnegie Libraries across America. New York: John Wiley & Sons, 1977.

Koch, Theodore W. A Book of Carnegie Libraries. New York: H. W. Wilson Co., 1917.

Martin, Marilyn. “From Altruism to Activism: The Contribution of Literary Clubs to Arkansas Public Libraries, 1885–1935.” Arkansas Historical Quarterly 55 (Spring 1996): 64–94.

Nasaw, David. Andrew Carnegie. New York: Penguin Press, 2006.

Schmidt, Sabine, and Don House. Remote Access: Small Public Libraries in Arkansas. Fayetteville: University of Arkansas Press, 2021.

Schuette, Shirley, and Nathania Sawyer. From Carnegie to Cyberspace: 100 Years at the Central Arkansas Library System. Little Rock: Butler Center Books, 2010.

Van Slyck, Abigail A. Free to All: Carnegie Libraries & American Culture, 1890–1920. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1995.

Wheeler, Elizabeth L. “Isaac Fisher: The Frustrations of a Negro Educator at Branch Normal College, 1902–1911.” Arkansas Historical Quarterly 41 (Spring 1982): 3–50.

John Spurgeon

Bella Vista, Arkansas

Arkansas Library Association

Arkansas Library Association Carnegie Library at Eureka Springs

Carnegie Library at Eureka Springs  Conway County Library

Conway County Library  Eureka Springs Library

Eureka Springs Library  Little Rock Public Library

Little Rock Public Library  Morrilton Library

Morrilton Library

Selection from actor Laurence Luckinbills remarks at a UA Library press conference, June 18, 2012: I love libraries. My first visit to one was in Fort Smith seventy years ago. I was seven. My aunt, who was a schoolteacher , took me to get my first library card. She had noticed that I had put my nose in my seventh birthday giftThe Adventures of Robin Hoodand never taken it out. She and the librarian had signed me up and walked me into The Reading Room (a whole room for it!) then shown me The Stacks! I was now important. Trusted. A man. I was a member of The Carnegie Library in Fort Smith, Arkansas! I wandered into the stacksthe jungle of books! Time stopped as I read, or tried to read, the titles of books I could not read and some I knew I could easily read. Robin Hood was there, and Tom Sawyer, Tarzan of the Apes, and some guys named the Hardy Boys, whom I got to know later. The librarian looked at the pile of books I had brought her. She smiled. Do you want to take these home? Take them homecould it be true? Could I? Can I take them home? I squeaked. For two weeks, she said, and opened each and took two cards out of a paper pocket in the back cover (secret pocket!). She picked up a little tool and pressed it on an ink pad , printing a date on each one. My aunt and I walked down the marble staircase to the street. If I finish them before two weeks, can I go and get more? She smiled, as she always did with me, Why, I believe you can, Larry, she said in her soft Arkansas lilt.