calsfoundation@cals.org

Mitchell v. United States

Mitchell v. United States et al., 313 U.S. 80 (1941), came on appeal to the U.S. Supreme Court, challenging discriminatory treatment of railroad accommodations for African-American passengers on interstate train coaches passing through Arkansas, where a state law demanded segregation of races but equivalent facilities. The Supreme Court had held in earlier cases that it was adequate under the Fourteenth Amendment for separate privileges to be supplied to differing groups of people as long as they were treated similarly well. Originating in Arkansas in April 1937, the suit worked its way through the regulatory and legal system, finally ending up on the calendar of the Supreme Court in 1941.

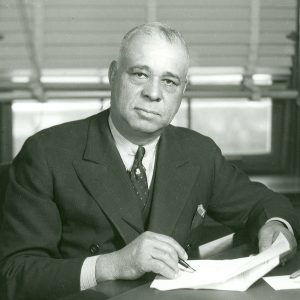

The circumstances surrounding the matter began after the only African American in the U.S. Congress, Representative Arthur Wergs Mitchell, a Democrat of Illinois, opted to spend a two-week vacation in Hot Springs (Garland County). He purchased a first-class railroad ticket, costing three cents per mile, from the Illinois Central Railroad Company in Chicago. Beginning on April 20, 1937, the trip involved the Illinois Central and the Chicago, Rock Island and Pacific Railroad. Traveling through Memphis, Tennessee, Mitchell transferred to the Chicago, Rock Island and Pacific line on the morning of April 21, requesting a Pullman sleeper coach, which cost an additional ninety cents, headed for Hot Springs. As the train crossed the Mississippi River into Arkansas, Conductor Albert W. Jones proceeded to collect fares. While in St. Francis County, Jones was startled to find an African American seated in the “white” section and immediately directed Congressman Mitchell to move to the African-American car.

Conductor Jones’s actions were based on his obligation to enforce the Arkansas Separate Coach Law of 1891 along any of Arkansas’s 2,063 miles of track. The rule, branded a “Jim Crow” law, required railroads operating in Arkansas to establish “equal but separate and sufficient” coaches for segregating white and black passengers, as well as commanding railroad employees to enforce the law or be fined $25 to $50; passengers who refused their instructions could be fined from $10 to $200.

Mitchell, due to his congressional status and purchase of the first-class ticket, refused to comply. Conductor Jones said to him, “It don’t make a damn bit of difference who you are—as long as you a nigger you can’t ride in this car.” Under threat of stopping the train and being arrested by the nearest sheriff if he did not proceed to the “colored passenger” coach, Mitchell moved to the designated area, although his luggage remained in the Pullman coach. The conductor later advised Mitchell that he could ask for a refund for the Memphis to Hot Springs portion of the fare as coach was only two cents per mile.

Mitchell never mentioned the incident during his two weeks in Hot Springs at his lodgings in the Pythian Hotel & Baths. The governor, Little Rock (Pulaski County) mayor, and the president of the Little Rock Chamber of Commerce all sent letters welcoming Mitchell. In a scheduled Little Rock speech before a mixed audience, the congressman was introduced by U.S. District Attorney Fred A. Isgrig, but again at no time did he mention the confrontation on the train. Upon his return trip to Chicago, Mitchell rode in the “Jim Crow” car without being directed to do so.

Back in Chicago, Congressman Mitchell, himself a lawyer, consulted with attorney Ralph E. Westbrook, and together they filed a personal damages lawsuit for $50,000 against the railroads in state court, along with a complaint with the Interstate Commerce Commission (ICC). Mitchell claimed that the African-American accommodations were not equal, nor should they be enforced by the ICC. He described the Jim Crow facilities thusly: “[T]he car was divided by partitions and partly used for carrying baggage,…poorly ventilated, filthy, filled with stench and odors emitting from the toilet and other filth, which is indescribable.” As for the language of Conductor Jones toward a member of the U.S. Congress, Mitchell described it as “too opprobrious and profane, vulgar and filthy to be spread upon the records of this court.” The “colored” cars were further described as not air-conditioned and divided by partitions for “colored smokers, white smokers, and colored men and women. A toilet was in each of the three sections, but only the one in the women’s section flushed and was for the exclusive use of colored women. The car was without wash basins, soap, towels, or running water, except in the women’s section.”Correspondingly, the “white” cars were described as in excellent condition, modern, air-conditioned, and equipped with hot and cold running water, soap, and towels, along with flushable toilets for both men and women; too, first-class passengers had sole use of the only dining-car and observation-parlor car.

The ICC dismissed the complaint, with the twelve-member board voting seven to five, noting “the discrimination and prejudice was plainly not unjust or undue.” Mitchell appealed the ICC ruing to the U.S. District Court for the Northern District of Illinois, but it also dismissed the complaint, noting that “the small number of colored passengers asking for first-class accommodations justified an occasional discrimination against them because of their race.” Mitchell appealed that ruling directly to the U.S. Supreme Court, where he presented oral arguments himself.

On April 28, 1941, four years and seven days from the original incident, Chief Justice Charles Evans Hughes delivered the unanimous opinion of the Court: “This was manifestly a discrimination against him [Mitchell] in the course of his interstate journey and admittedly that discrimination was based solely upon the fact that he was a Negro. The question whether this was a discrimination forbidden by the Interstate Commerce Act is not a question of segregation but equality of treatment. The denial to appellant equality of accommodations because of his race would be an invasion of a fundamental right which is guaranteed against state actions by the 14th Amendment.” The Supreme Court reversed the U.S. District Court decree and remanded the case, also directing that the ICC order be set aside and sent back for further proceedings in conformity with the Supreme Court opinion.

Not until January 1956 was segregation on interstate transportation ended on railroads, and not until 1973 did the Arkansas General Assembly finally repeal the Separate Coach Law of 1891, originally authored by state Senator John N. Tillman—afterward president of the University of Arkansas (UA) in Fayetteville (Washington County) from 1905 to 1912. Eventually, in the civil lawsuit, Mitchell reached an out-of-court settlement, and additionally he received $3,750 and court costs. However, his political career in Chicago was over because of his having angered the white political establishment. Mitchell did not seek reelection but instead retired and moved to Petersburg, Virginia, becoming a gentleman farmer on his estate, named Rose-Anna Gardens, where he was laid to rest in 1968.

For additional information:

Duis, Perry R. “Arthur W. Mitchell: New Deal Negro in Chicago.” Master’s thesis, University of Chicago, 1966.

Knapp, John Morris. A Carpetbagger in Reverse: Arthur W. Mitchell, America’s First Black Democratic Congressman. Tuscaloosa: University of Alabama Press, 2024.

Kornweibel, Theodore, Jr. Railroads in the African American Experience: A Photographic Journey. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 2010.

Litwack, Leon F. Trouble in Mind: Black Southerners in the Age of Jim Crow. New York: Random House, 1998.

“New Notes of Historical Interest.” Arkansas Historical Quarterly 1 (March 1942): 86.

Nordin, Dennis S. The New Deal’s Black Congressman: The Life of Arthur Wergs Mitchell. Columbia: University of Missouri Press, 1997.

“Races: Jim Crow Suit.” Time, May 24, 1937. Online at http://content.time.com/time/subscriber/article/0,33009,848678,00.html (accessed February 14, 2022).

“Supreme Court: No More Jim Crow?” Time, May 12, 1941. Online at http://content.time.com/time/subscriber/article/0,33009,795237,00.html (accessed February 14, 2022).

Teague, Greyson. “Ticket to Ride: Arthur Mitchell and the Fight to Dismantle Jim Crow in Transportation.” Arkansas Historical Quarterly 80 (Autumn 2021): 287–308.

Wormser, Richard. The Rise & Fall of Jim Crow: The African-American Struggle against Discrimination, 1865–1954. New York: Grolier Publishing, 1999.

John Spurgeon

Bella Vista, Arkansas

Comments

No comments on this entry yet.