calsfoundation@cals.org

Republican Party

Few state political parties have experienced histories as hapless as that of Arkansas’s Republicans. Following the Democratic disenfranchisement of the state’s African Americans (most of whom identified as Republicans) in the last years of the nineteenth century, Arkansas’s Republicans focused more on gaining patronage from Republican administrations in Washington DC than on ardently contesting elections at home that inevitably would be lost. Moreover, until the 1990s, Republican victories in statewide elections were always attributable to Democratic failings rather than Republican ingenuity. But as the twentieth century closed, the state’s Republicans began to become consistently competitive, with markedly improved candidates for office expressing a conservative ideology increasingly preferable to Arkansas voters. Recent election cycles, especially the 2014 election, have made the Republican Party the dominant force in Arkansas politics.

The Republican Party of Arkansas was officially formed in April 1867. Quickly, Powell Clayton—a Union officer during the Civil War who moved to Arkansas to begin life as a planter early in Reconstruction—became the key leader of the party. During Reconstruction, Republicans were elected to state offices at all levels—including governor. This Republican dominance ended with the enfranchisement of former Confederate loyalists as Reconstruction ended in the state in 1873. Even after Reconstruction, the Grand Old Party (GOP) remained visible, with newly enfranchised African Americans joining white Republican loyalists in support of the party, with many being elected to local office and the Arkansas General Assembly. Still, as a political minority, the Republicans who succeeded politically after Reconstruction beyond the local level were those who joined in electoral unions with populist coalitions. Disenfranchisement of black citizens, in the form of “reforms” passed by the Democratic-controlled legislature in the early 1890s, ended any Republican viability. In order to attract white Democrats, one faction within the Republican Party, known as the “Lily Whites,” sought the exclusion of African Americans from party ranks, while black Republicans and their allies constituted the opposing “Black and Tans” faction.

After disenfranchisement, the only area with significant numbers of white Republicans was northwest Arkansas, where Republican loyalties could be traced to the native Unionists of the Civil War era. Arkansas Republicans became known as “post office Republicans” because, rather than putting energy into developing a political party to challenge Democrats in Arkansas, the activists simply sought the bevy of federal appointments (including postmaster positions) that came with Republican presidential victories.

The small number of state legislators who identified themselves as Republicans in the first eight decades of the twentieth century came from the hill counties. It was in this quadrant that modern Republican development was first evident. In 1966, Republican John Paul Hammerschmidt won a U.S. House seat from the area. He would not relinquish it until retiring in 1992, often facing only token reelection opposition. Hammerschmidt’s only truly close call came in 1974 (an electoral cycle where the Watergate crisis threatened all Republicans), when he beat upstart law professor Bill Clinton.

Also in 1966, Republicans gained an even higher profile win with election of the state’s first Republican governor of the modern era: multimillionaire Winthrop Rockefeller, a 1950s transplant from New York. (He was joined in success by Republican lieutenant governor candidate Maurice “Footsie” Britt, a World War II hero.) But Rockefeller’s coalition differed dramatically from his fellow Republicans beginning to gain success elsewhere in the South. In other states, it was conservative whites fleeing to a Republican Party from a national Democratic Party increasingly liberal on civil rights. Instead, Rockefeller’s gubernatorial victory (and 1968 reelection) relied on progressive Democrats and newly enfranchised black voters fleeing a state party that was, in their eyes, too resistant to change. Rockefeller faced a Democratic legislature that consistently shot down his progressive proposals. As a result, when the state Democratic Party learned its lesson and nominated the first in a long line of progressive gubernatorial candidates in 1970, the Rockefeller coalition disintegrated.

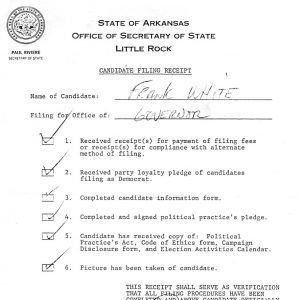

Rockefeller’s death in 1973 devastated the state Republican Party, as it lost a patron committed to investing in the development of a two-party state. Despite the historic success of Republican presidential candidates Richard Nixon (1972), Ronald Reagan (1980 and 1984), and George H. W. Bush (1988) in a state that had not given the GOP its Electoral College votes since Reconstruction, Republican success in state and congressional politics in the 1970s and 1980s was rare. In 1978, Ed Bethune did gain a second congressional seat for the party, from the district covering central Arkansas, and he held it for three terms. Also, a chaotic first administration for Democratic governor Bill Clinton created an opening for Republican Frank White in 1980. In the campaign, White hammered Clinton’s support of fee increases for license plates and his inability to prevent the placement of Cuban refugees—who later rioted—at Fort Chaffee; White won a tight election. Two years later, Clinton defeated White and returned to office.

In 1989, Bethune’s Democratic replacement, Tommy Robinson, announced his switch to the Republican Party—the party’s highest-profile capture of a Democratic officeholder. Soon after, Robinson announced that he would challenge Clinton for governor in 1990. While Robinson had the support of national GOP leaders, he failed to win a Republican primary (open to voters of either party) over another party-switcher, Sheffield Nelson. Clinton defeated Nelson solidly in the general election and soon announced his candidacy for president in the 1992 election. The 1992 election produced not only an Arkansan president but also another Republican congressman from the state, with Jay Dickey elected from Arkansas’s Fourth District (south Arkansas) over a scandal-plagued Democratic nominee in 1992; Dickey would serve four terms before being defeated in 2000.

Clinton’s departure for Washington DC in 1993 produced new opportunities for Arkansas Republicans. A hotly contested special election to fill the lieutenant governorship was won by the party’s nominee for the U.S. Senate a year earlier, Mike Huckabee. Huckabee, a Baptist minister and former president of the Arkansas Baptist State Convention, showed a personal style attractive to Arkansas voters. After being reelected in 1994, Huckabee ascended to the governorship in 1996 after a federal jury convicted Democratic governor Jim Guy Tucker on charges emanating out of—but not connected to—an investigation of Clinton’s business dealings in Arkansas. The vacancy in the lieutenant governorship was filled in a special election by another Republican, Winthrop Paul Rockefeller, son of the late governor. In contrast to the previous victories of Rockefeller and White, these victories indicated an era of more stable success for the party.

Huckabee became the longest-serving Republican governor in Arkansas, winning elections in 1998 and 2002. His conservative populist ideology and savvy communication skills made him the first true state political “star” for the GOP in the modern era. While his decade as governor presented grand opportunities to fill the hundreds of positions in the state executive branch with Republican loyalists and to take on national Republican leadership roles, Huckabee evidenced less interest in building a strong Republican party organizationally.

The two other dominant state Democratic politicians of the modern era, Dale Bumpers and David Pryor, completed their final terms in the U.S. Senate, leaving openings for the GOP. While Republicans failed to gain Bumpers’s seat, Pryor’s was won by Tim Hutchinson, the Republican congressman who had filled Hammerschmidt’s void, in 1996. Thus, Arkansas became the next-to-last Southern state to elect a Republican U.S. senator since the direct election for that office began (Louisiana was the last). Hutchinson’s brother, Asa, the state GOP’s former chairman, was elected as his replacement in Congress. (When Asa Hutchinson accepted an appointment in the George W. Bush administration in 2001, Republican John Boozman replaced him.) Arkansas’s newly successful Republicans had much more in common ideologically with Republicans elsewhere in the South than did the elder Rockefeller, generally exhibiting conservative positions on both economic and social issues.

In 2010, Congressman Boozman easily defeated U.S. Senator Blanche Lincoln and, because of victories in the First and Second Congressional Districts, Arkansas had a majority Republican congressional delegation for the first time since Reconstruction. Even more telling were victories in three statewide constitutional officers and in over forty percent of legislative races. Two years later, Republicans captured a majority in the Arkansas General Assembly, as well as sweeping the state’s four spots in the U.S. House of Representatives. Demographic trends have favored the party’s future development, as the fastest-growing areas of the state—northwestern Arkansas and the suburbs around Little Rock (Pulaski County)—are also the areas where Republicans have found the greatest success. In 2014, the Republican Party captured victories in all of the state’s congressional districts, the one open U.S. Senate seat, and all of the state constitutional offices, as well as increasing its majorities in both houses of the Arkansas General Assembly, thus bringing Arkansas into line with the rest of the American South politically. Two years later, the state party managed to gain a supermajority in the Arkansas House of Representatives following the defection of two Democratic Party members to Republican ranks in the wake of an election that solidified Republican power both nationally and locally. The party expanded its supermajority in both houses of the state legislature in 2022; in addition, Republicans in the Senate adopted a rule change to limit Democratic representation on committees.

At the biannual state convention in June 2024, the party members voted to close its primaries, meaning that voters will have to register as a Republican to vote in a Republican primary; the change came from state convention leadership rather than the party’s rules committee, which had declined the proposed rule change. The secretary of state‘s office declared that this move will require a change in state law to take effect, but party leadership disagreed. On July 25, 2024, the party’s executive committee reversed course, declaring the June vote null and void. On August 26, a group of delegates to the party’s state convention filed a federal lawsuit in the U.S. District Court for the Eastern District of Arkansas against Joseph Wood, state party chairman, and Secretary of State John Thurston, alleging both of depriving the plaintiffs of their civil rights by not abiding by the vote of the delegates. On December 2, 2024, the Republican Party of Arkansas executive committee voted to dissolve the Saline County Republican Committee, whose leaders had led the push for closed primaries, and on May 5, 2025, U.S. District Judge Brian S. Miller dismissed the lawsuit seeking to close the primary. However, on June 21, 2025, the Republican Party of Arkansas State Committee did vote to bar registered Democrats from voting in Republican primary elections.

For additional information:

Barth, Jay, Diane D. Blair, and Ernie Dumas. “Arkansas: Characters, Crises, and Change.” In Southern Politics in the 1990s, edited by Alexander P. Lamis. Baton Rouge: Louisiana State University Press, 1999.

Blair, Diane D., and Jay Barth. Arkansas Politics and Government: Do the People Rule? 2d ed. Lincoln, NE: University of Nebraska Press, 2005.

Childs, Lisa C. “Reexamining the Origins of Arkansas’s Republican Party.” Arkansas Historical Quarterly 79 (Winter 2020): 317–347.

Coon, Ken. Heroes and Heroines of the Journey: The Builders of the Modern Republican Party of Arkansas. N.p.: 2017.

Davis, John C. From Blue to Red: The Rise of the GOP in Arkansas. Fayetteville: University of Arkansas Press, 2024.

Davis, John C., Andrew J. Dowdle, and Joseph G. Giammo. “Arkansas: Should We Color the State Red with a Permanent Marker?” In The New Politics of the Old South: An Introduction to Southern Politics, 7th ed., edited by Charles S. Bullock III and Mark J. Rozell. Lanham, MA: Rowman & Littlefield, 2022.

Dillard, Tom W. “To the Back of the Elephant: Racial Conflict in the Arkansas Republican Party.” Arkansas Historical Quarterly 33 (Spring 1974): 3–15.

Kirk, John. “A Southern Road Less Traveled: The 1966 Arkansas Gubernatorial Election and (Winthrop) Rockefeller Republicanism in Dixie.” In Painting Dixie Red: When, Where, Why, and How the South Became Republican, edited by Glenn Feldman. Gainesville: University Press of Florida, 2011.

Lewis, Todd E. “‘Caesars Are Too Many’: Harmon Liveright Remmel and the Republican Party of Arkansas.” Arkansas Historical Quarterly 56 (Spring 1997): 1–25.

Rector, Charles J. “Lily-White Republicanism: The Pulaski County Experience, 1888–1930.” Pulaski County Historical Review 42 (Spring 1994): 2–18.

Russell, Marvin F. “The Rise of a Republican Leader: Harmon L. Remmel.” Arkansas Historical Quarterly 36 (Autumn 1977): 234–257.

Urwin, Cathy Kunzinger. Agenda for Reform: Winthrop Rockefeller as Governor of Arkansas. Fayetteville: University of Arkansas Press, 1991.

Wickline, Michael R. “State to Limit GOP Primary Vote Eligibility.” Arkansas Democrat-Gazette, September 15, 2025, pp. 1A, 3A. Online at https://www.arkansasonline.com/news/2025/sep/14/state-set-to-limit-eligibility-for-voting-in-gop/ (accessed September 15, 2025).

Jay Barth

Hendrix College

Arkansas Quarter Press Conference

Arkansas Quarter Press Conference  "Footsie" Britt Campaign Sticker

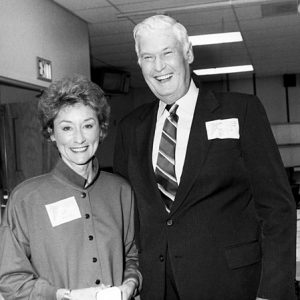

"Footsie" Britt Campaign Sticker  Gay White and Footsie Britt

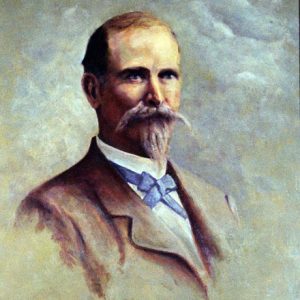

Gay White and Footsie Britt  Powell Clayton

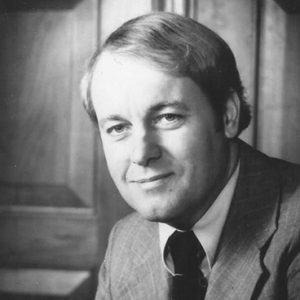

Powell Clayton  John Paul Hammerschmidt

John Paul Hammerschmidt  Asa Hutchinson at CSA Arrest

Asa Hutchinson at CSA Arrest  Hutchinson, Hutchinson, and White

Hutchinson, Hutchinson, and White  Peggy Jeffries with Lonoke County Republicans

Peggy Jeffries with Lonoke County Republicans  Sheffield Nelson

Sheffield Nelson  Old Guard Home Parody

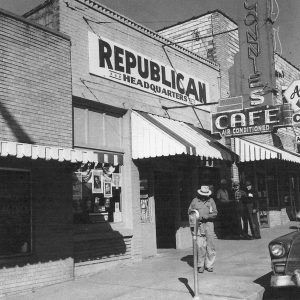

Old Guard Home Parody  Republican Headquarters in Mountain Home

Republican Headquarters in Mountain Home  Republican Party Leaders

Republican Party Leaders  Lincoln Day Dinner Flyer

Lincoln Day Dinner Flyer  Republican Stickers

Republican Stickers  Winthrop Rockefeller on Victory Train

Winthrop Rockefeller on Victory Train  Frank White's Gubernatorial Candidate Form

Frank White's Gubernatorial Candidate Form

Comments

No comments on this entry yet.