calsfoundation@cals.org

Arkansas Department of Corrections

The umbrella entity of the Arkansas Department of Corrections, created by Act 910 of 2019, is composed of over 6,000 employees within the following: the Division of Correction (formerly the Arkansas Department of Correction), the Division of Community Correction (formerly Arkansas Department of Community Correction), the Corrections School System (Arkansas Correctional School District and Riverside Vocational Technical School), and the Office of the Criminal Detention Facility Review Coordinator, along with the administrative functions of the Criminal Detention Facility Review Committees, Parole Board, Sentencing Commission; and State Council for the Interstate Commission for Adult Offender Supervision.

The Division of Correction (ADC) enforces the court-mandated sentences for people convicted of crimes at a variety of prison facilities located in twelve counties across the state. Its central offices are in Pine Bluff (Jefferson County).

The first state penitentiary was built in 1839–40 in Little Rock (Pulaski County) at the site of what is now the Arkansas State Capitol. After legislation passed in 1899 calling for a new seat of government, it was relocated to a fifteen-acre site southwest of the city, explicitly to make room for the new capitol building. This second penitentiary was popularly known as “The Walls.” In 1902, the Cummins State Prison Farm was established in Lincoln County, and land was purchased in 1916 for the Tucker State Prison Farm in Jefferson County. Prisoners from “The Walls,” which closed in 1933, were transferred to the new facilities.

Act 1 of 1943 standardized numerous boards of state agencies, including the State Penitentiary Board, but it was not until the February 21, 1968, passage of Act 50 that the Arkansas Department of Correction was established, with the State Penitentiary Board reconstituted as the State Board of Correction to oversee it. The act also established a diagnostic center as part of the ADC to conduct “social, medical and psychiatric studies of persons committed to the Department” and coordinate with other state agencies for any needed medical services for inmates. The act required the ADC to establish standards for medical care and put in place the option of transferring “mentally ill and mentally retarded inmates” to the Arkansas State Hospital.

This reorganization followed a series of high-profile embarrassments for the state’s prison system. The 1965 court case of Talley v. Stephens restricted the state’s use of corporal punishment, requiring that safeguards be put in place to prevent excessive punishment and that better care be provided for prisoners. In August 1966, Governor Orval Faubus opened an investigation into allegations of wrongdoing among prison employees, and a riot broke out at Cummins the following month. In 1968, prison warden Thomas O. Murton made public allegations that murders of inmates had taken place in state prisons, among other abuses; these were later published in a book, Accomplices to the Crime: The Arkansas Prison Scandal (1969), which inspired the movie Brubaker (1980). The February 9, 1968, issues of Newsweek and Time magazines carried stories relating harsh conditions in Arkansas prisons, including allegations of murder and torture.

The 1968 reorganization did not produce immediate results, and the following year, large portions of Arkansas’s prison system were ruled unconstitutional in Holt v. Sarver. In 1970, Judge J. Smith Henley ruled the entire state’s prison system unconstitutional due to the persistence of cruel and unusual punishment and the ADC’s interference with prisoners’ access to the court system. Only in 1973 did Henley release the ADC from his jurisdiction, citing improvements. That same year, Act 279 created a school district within the ADC for the “institution of basic education for inmates…to the end that said inmates may improve their minds and characters and become less likely to commit further crimes.” The following year, the state located its first work release center in Benton (Saline County). However, the ADC continued to attract controversy and scandal in the ensuing years, most notably over its role in what has been called the Arkansas prison blood scandal, in which blood extracted from prisoners, many with hepatitis and/or HIV, was sold to blood brokers and shipped across the globe, infecting untold numbers of people.

The ADC operates twenty different facilities, including Varner Unit, a super maximum security (supermax) facility that houses inmates scheduled for the death penalty, though executions take place at the Cummins Unit. In addition, the ADC operates a sex offender registry and maintains a list of escaped prisoners, both available online; the agency’s website also features a searchable database of prisoners in state facilities. The ADC actively cooperates with the Arkansas Victim Notification Program (VINE), created by Act 1262 of 1997 and provided by the Arkansas Crime Information Center. The VINE program allows victims of crimes to be notified regarding any change in a prisoner’s status.

Prior to 2019, the ADC was a cabinet-level department known as the Arkansas Department of Correction until the creation of the new Arkansas Department of Corrections as part of the Transformation and Efficiencies Act of 2019 (Act 910), which created the Board of Corrections to oversee the ADC, the Division of Community Correction, and the Corrections School System.

In 2023, the Arkansas General Assembly passed, and Governor Sarah Huckabee Sanders signed, Act 185, which amended the law concerning the secretary of the Department of Corrections, making that person serve at the pleasure of the governor, rather than the Board of Corrections. Act 659, passed that same year, states that the directors of both the Division of Correction and the Division of Community Correction serve at the pleasure of the secretary rather than the board. Conflict between the governor and the board came to a head later in the year when Gov. Sanders publicly called for the ADC to increase the number of prisoners detained in state facilities. Board members expressed concern about prison overcrowding, especially amid staff shortages, but Corrections Secretary Joe Profiri sided with the governor. On December 14, 2023, the board voted to suspend Profiri with pay and to direct outside counsel to file a lawsuit against Sanders, Profiri, and the ADC, asserting that Act 185 conflicted with Amendment 33 of the Arkansas Constitution, which was designed to protect state agencies from political influence. The next day, Pulaski County Circuit Judge Patricia James issued a temporary restraining order, ruling that Acts 185 and 659 usurped the board’s power under the state constitution. Also on December 15, Attorney General Tim Griffin filed suit against the Board of Corrections, alleging that the board had violated the state’s Freedom of Information Act in hiring outside counsel during a closed session, but on December 19, Judge Tim Fox of the Pulaski County Circuit Court ruled that Griffin’s lawsuit violated his statutory duty to represent the state, meaning that the attorney general was essentially suing his own clients, and Fox threatened to dismiss the case without prejudice, which he did on January 22, 2024. On January 4, 2024, Judge James issued a preliminary injunction, holding Acts 185 and 659 in abeyance until the lawsuit challenging their constitutionality was completed. On April 23, 2024, the Joint Performance Review Committee of the state legislature found that the Arkansas Board of Corrections erred in hiring outside counsel and violated the Freedom of Information Act, referring its findings to the Arkansas Legislative Council.

On December 22, 2023, it was announced that Benny Magness, chair of the Board of Corrections, had asked Gov. Sanders to activate Arkansas National Guard personnel to “help fill in staffing gaps within the Division of Correction.” The following day, Sanders released a letter calling upon Magness to resign. Magness refused, and on January 10, 2024, the Board of Corrections fired Secretary Profiri; Gov. Sanders subsequently hired him as a senior advisor. The board hired former state senator Eddie Joe Williams on January 31, 2024, to serve as interim corrections secretary, but he resigned on February 6, 2024. Gov. Sanders subsequently nominated Lindsey Wallace to serve as corrections secretary after reportedly conferring with Magness on the matter.

| Facility | Location | Capacity |

| Barbara Ester Unit | Jefferson County | 580 |

| Benton Unit | Saline County, south of Benton | 325 |

| Cummins Unit | Lincoln County, south of Pine Bluff | 1,725 |

| Delta Regional | Chicot County, southeast of Pine Bluff | 599 |

| East Arkansas Regional Unit | Lee County, southeast of Forrest City | 1,432 |

| Grimes Unit | Jackson County, northeast of Newport | 1012 |

| J. Aaron Hawkins Sr. Center | Wrightsville, Pulaski County | 212 |

| Maximum Security Unit | Jefferson County, northeast of Pine Bluff | 532 |

| McPherson Unit | Jackson County, northeast of Newport | 971 |

| Mississippi County Work Release Center | Mississippi County, west of Luxora | 121 |

| North Central Unit | Calico Rock, Izard County | 800 |

| Northwest Arkansas Work Release Center | Springdale, Washington County | 100 |

| Ouachita River Unit | Hot Spring County, south of Malvern | 1,782 |

| Pine Bluff Unit | Jefferson County, west of Pine Bluff | 430 |

| Randall L. Williams Correctional Center | Jefferson County, west of Pine Bluff | 562 |

| Texarkana Regional Correction Center | Texarkana, Miller County | 128 |

| Tucker Unit | Jefferson County, northeast of Pine Bluff | 1,126 |

| Willis H. Sargent Training Academy | England, Lonoke County | |

| Varner Unit | Lincoln County, south of Pine Bluff | 1,714 |

| Wrightsville Unit | Wrightsville, Pulaski County | 850 |

For additional information:

Arkansas Department of Corrections. http://www.adc.arkansas.gov (accessed April 26, 2022).

Campbell, Matt. “The Queen’s Gambit: Gov. Sanders and Co. Play Political Games with Overcrowded Prisons.” Arkansas Times, March 2024, pp. 28–33. Online at https://arktimes.com/arkansas-blog/2024/02/28/the-queens-gambit-gov-sanders-and-co-play-political-games-with-overcrowded-prisons (accessed March 1, 2024).

Crosley, Clyde. Unfolding Misconceptions: The Arkansas State Penitentiary, 1836–1986. Arlington, TX: Liberal Arts Press, 1986.

Earley, Neal. “Prison-Board Bypass Barred for Governor.” Arkansas Democrat-Gazette, December 16, 2023, pp. 1A, 5A. Online at https://www.arkansasonline.com/news/2023/dec/15/judge-temporarily-blocks-sanders-from-bypassing/ (accessed December 18, 2023).

Snyder, Josh. “Judge: AG Has 30 Days to Avoid Suit Dismissal.” Arkansas Democrat-Gazette, December 20, 2023, pp. 1A, 5A. Online at https://www.arkansasonline.com/news/2023/dec/19/judge-orders-tim-griffin-to-reach-agreement-with/ (accessed December 20, 2023).

Staff of the CALS Encyclopedia of Arkansas

Corrothers, Helen Gladys Curl

Corrothers, Helen Gladys Curl Hutto, Terrell Don

Hutto, Terrell Don Law

Law Lockhart, Art

Lockhart, Art Prison Reform

Prison Reform Arkansas State Penitentiary

Arkansas State Penitentiary  Arkansas State Penitentiary

Arkansas State Penitentiary  Arkansas State Penitentiary

Arkansas State Penitentiary  Arkansas State Penitentiary

Arkansas State Penitentiary  Benton Work Release Center

Benton Work Release Center  Johnny Cash at Cummins

Johnny Cash at Cummins  Cummins Baptism

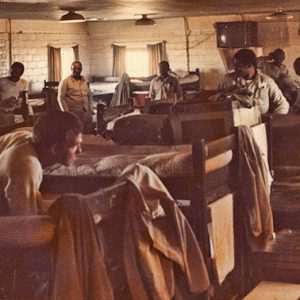

Cummins Baptism  Cummins Barracks

Cummins Barracks  Cummins Chapel

Cummins Chapel  Cummins Unit

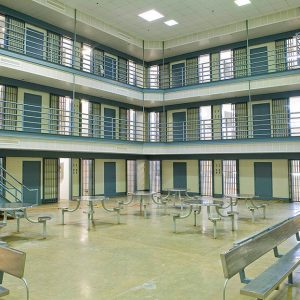

Cummins Unit  East Arkansas Regional Unit

East Arkansas Regional Unit  Benjamin Laney

Benjamin Laney  McPherson and Grimes Units

McPherson and Grimes Units  Ouachita River Unit

Ouachita River Unit  Prison Hospital

Prison Hospital  Prison Hospital

Prison Hospital  Texarkana Regional Correction Center

Texarkana Regional Correction Center  Varner Unit

Varner Unit  Women Prisoners

Women Prisoners

My 23-year-old son is in the hole at Cummins for three months because he got high on weed. He suffers from ADHD, anxiety, and depression but can’t get any mental health help. I pray he isn’t going to be the 7th inmate this year to commit suicide while in solitary confinement. It’s sad how this system works.

As a nineteen-year-old man doing time in both Cummins and Tucker Units in 1969-1971, I received treatment that was more than any human being should have to endure at the hands of another. Rape, torture, beatings, and starvation all went hand in hand for me. Now forty years later, I still wake up screaming in the middle of the night. I am told that very little has changed since then. May God help those who survived those years and those who brought the cruelty to them. It is time for change in our world.