calsfoundation@cals.org

Caves and Caverns

Caves and caverns are natural underground openings large enough for humans to enter. They are primarily formed by volcanic activity or the eroding effects of water and wind. The caves of Arkansas are of the latter variety, the result of the dissolution of limestone and other soluble rock throughout the state’s mountainous regions. Hence, the highest concentration of caves is in the northwest and north-central areas of the state.

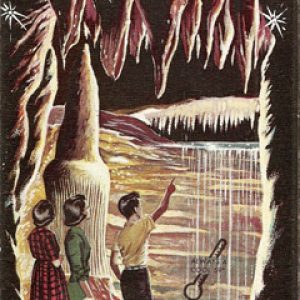

Arkansas boasts several caves of sufficient size to be of interest to tourists and spelunkers, and all of these can be described as “living caves”—caves in which water remains present, along with its continuing ability to alter cave structure. The caves of Arkansas display vast arrays of stalactites and stalagmites, underground streams (including some with navigable sections), underground bridges and waterfalls, ancient sea fossils, and more. Archaeological evidence of Native American habitation dates back thousands of years.

Though now primarily tourist attractions, caves have also played various roles in the history of Arkansas. The first school in the state is believed to have held its classes in a cave near Ravenden Springs (Randolph County). Rumors of treasure buried by Spanish explorer Hernando de Soto, and whispers of curses on those who seek it, still swirl around a cave in Little River County. Some claim that silver ingots occasionally wash out from Mill Ford Cave, now covered by Beaver Lake, and the saltpeter and lead found in caves provided munitions for the Confederacy during the Civil War.

In more recent times, caves have attracted those who had nowhere else to go or did not wish to be found; transients and those down on their luck have sometimes made caves their temporary shelter. Some have chosen caves as long-term residences. There has been at least one case, near Eureka Springs (Carroll County), of a person who left modern society for the solitude of cave dwelling. Jake Call bought 120 acres of wilderness property in 1936 intending to build a house. Instead, he made his home for at least thirty years in a 10′ x 40′ cave on the property.

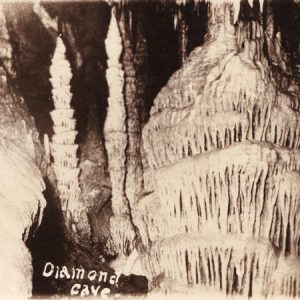

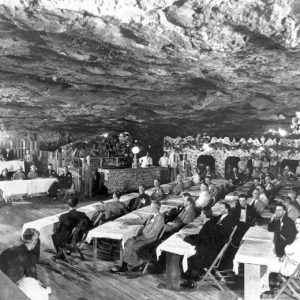

In the 1960s and 1970s, the caves of Arkansas attracted the attention of state and federal governments for their ability to shelter people, this time as nuclear fallout shelters. The presence of water and the constant cool temperature (along with the radiation-blocking benefit of subterranean living) made caves a sensible option for surviving a nuclear war. One holdover from the Cold War era is the Beckham Creek Cave Haven in Parthenon (Newton County), which has found new life as a luxury hotel; rooms and reception areas are available that allow for a comfortable underground stay. Two popular caves that became tourist attractions in the early twentieth century were Diamond Cave, which offered public tours into the 1990s, and Wonderland Cave, which served at various times as a nightclub and wine storage cellar. Both caves are closed to the public.

In 2009, officials with state and federal agencies began closing some caves in Arkansas to the public after a potentially lethal fungal infection, white nose syndrome, that originated on the East Coast spread to bat populations in the South. Other caves remain open but require visitors to use special gear to avoid contaminating the caves.

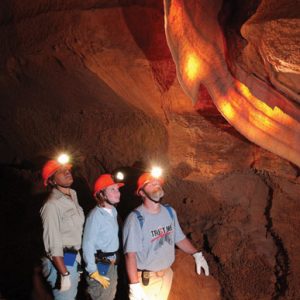

Guided tours are offered at Blanchard Springs Caverns, Bull Shoals Caverns, Cosmic Caverns, Hurricane River Cave, Mystic Caverns, Onyx Cave, Old Spanish Treasure Cave, and War Eagle Cavern, among others. Guided wild caving tours for those who are physically fit are offered at Hurricane River, War Eagle, Cosmic, and Blanchard Springs.

In 2020, the Arkansas National Heritage Commission began working in partnership with the Cave Research Foundation to create more complete maps and biological inventories of caves within the state.

For additional information:

Bleiberg, Larry. “Cold War Bunker in Ozarks Cave Is Now Cool Spot to Spend Vacation” Arkansas Democrat-Gazette. October 16, 2005, p. 3H.

Copeland, Clovis. “Caves Offer Shelter if Nuclear Attack Comes.” Arkansas Democrat. November 10, 1961, p. 9A.

“Christmas Tree in Big Cave for Half Century, Brought Community Peace and Plenty.” Arkansas Democrat. December 18, 1932, p. 10A.

Eley, Ashton. “Arkansas Scoured for Hidden Caves and Secrets Within.” Arkansas Democrat-Gazette, April 5, 2021, pp. 1B, 3B.

Graening, G. O., Danté B. Fenolio, and Michael E. Slay. Cave life of Oklahoma and Arkansas. Norman: University of Oklahoma Press, 2011.

Hull, Ralph. “Underground Stream Leads into Big Hurricane Cavern.” Arkansas Gazette. October 18, 1931, p. 9B.

“Legend of Spanish Treasure Clings to Cave.” Arkansas Democrat Magazine. November 12, 1967, p. 7.

Peacock, Leslie Newell. “Closing Caves, Sparing Bats.” Arkansas Times. March 25, 2010, p. 8.

Steele, Phillip. “Cave Dweller Likes Tourists, Befriends Animals.” Arkansas Democrat Magazine. November 17, 1968, p. 2.

Taylor, Michael Ray. Hidden Nature: Wild Southern Caves. Nashville, TN: Vanderbilt University Press, 2020.

Weaver, H. Dwight. The Wilderness Underground: Caves of the Ozark Plateau. Columbia, MO: University of Missouri Press, 1992.

Matthew Franks

Pulaski Technical College

Geography and Geology

Geography and Geology Karst Topography

Karst Topography Zero Mountain

Zero Mountain Beckham Creek Cave

Beckham Creek Cave  Blanchard Springs Caverns

Blanchard Springs Caverns  Blanchard Springs Caverns

Blanchard Springs Caverns  Blanchard Springs Caverns

Blanchard Springs Caverns  Bull Shoals Caverns Brochure

Bull Shoals Caverns Brochure  Cave Springs Cave Natural Area

Cave Springs Cave Natural Area  Chinn Spring Cave

Chinn Spring Cave  Cosmic Caverns

Cosmic Caverns  Devil's Den Cave

Devil's Den Cave  Diamond Cave Postcard

Diamond Cave Postcard  Diamond Cave Brochure

Diamond Cave Brochure  Foushee Cave Natural Area

Foushee Cave Natural Area  Hell Creek Natural Area

Hell Creek Natural Area  Hurricane River Cave

Hurricane River Cave  Indian Rock Cave

Indian Rock Cave  Mystic Caverns

Mystic Caverns  Wonderland Cave

Wonderland Cave  Zero Mountain Caverns

Zero Mountain Caverns

Comments

No comments on this entry yet.