calsfoundation@cals.org

Minstrel Shows

Popular during the nineteenth century, the minstrel show was one of the earliest forms of theatrical entertainment in the United States. The elements of the genre were developed during the 1820s and 1830s, and the first show fully dedicated to minstrelsy was staged in 1843 by the Virginia Minstrels. Early performances were given by white performers who used burnt cork to blacken their faces in order to represent different black characters. The white performers also drew heavily on the music produced by African Americans, and in particular plantation slaves in the South. The banjo, an instrument with origins in West Africa, and the “bones”—pairs of bones or wood that were struck against one another—quickly became part of the standard minstrel show, as did plantation songs of the South mixed with European forms. The popularity of minstrel shows quickly spread throughout the country, including Arkansas, with performances that consisted of a variety of different acts, including songs, dances, comic skits, and opera parodies. Much of the subject matter was based around southern life, and in particular southern plantation life, as was much of the music.

Initially, performances consisted of two separate parts, each dedicated to one of the two main stock minstrel show characters: the urban dandy (“Zip Coon”) and the plantation slave (“Jim Crow”). Shows offered a variety of different types of entertainment, including singing, dancing, stump speeches, skits, and parodies. As the minstrel show grew in popularity during the late 1840s and 1850s, a more defined three-part structure was developed. The first section focused on more polished popular songs, including those written by Stephen Foster, and had a more genteel feel than the other sections. The second section, known as the “olio,” could offer a variety of different types of entertainment, including singing, dancing, skits, and parodies of European operas. The third section had scenes set on southern plantations with its climax being the ensemble finale known as the “walk-around.” During this concluding section, all of the troupe’s members sang, danced, and joked, creating a final spectacle to end the night.

After the Civil War, the minstrel show had to compete with a number of new types of entertainment that developed during the late nineteenth and early twentieth century, including vaudeville, burlesque, revues, and musicals. Black minstrel troupes also emerged after the Civil War, frequently also in blackface. Elements of the minstrel tradition continued into the twentieth century and even into early motion pictures. Al Jolson, one of the top performers of the 1920s and 1930s, wore blackface on stage and film, and many early films focused on minstrelsy and minstrel show songwriters, including the Minstrel Man (1944) and Dixie (1943), a film about Daniel Emmett of the Virginia Minstrels.

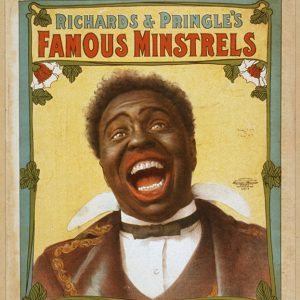

A number of prominent minstrel troupes toured Arkansas during the nineteenth and twentieth centuries. Both white and black minstrel troupes frequently toured the Arkansas Delta region, including the Al G. Fields Minstrels, Richard & Pringle’s Famous Georgia Minstrels, the Dandy Dixie Minstrels, Allen’s Minstrels, and the Florida Blossom Minstrels. Typically, the performances of both white and black minstrel groups were preceded by an afternoon parade to create greater interest in the ensuing performance that evening. Usually, the show would be held in a theater or under tents brought by the troupe.

The main difference between the white and black shows was that the black minstrel performances were largely for black audiences, and black minstrels also stuck to more familiar elements, such as songs and jokes with which the audience was already familiar. One top black minstrel group that toured Arkansas during the early twentieth century, when the performance style was in decline, was the Rabbit Foot Minstrels. They toured primarily in the South and helped launch the careers of blues performers Ma Rainey and Bessie Smith. The famous fiddle tune and Arkansas’s first unofficial state song “The Arkansas Traveler” also has its roots in the minstrel show, as it was frequently performed by different minstrel troupes.

Black and white minstrel shows continued to be staged in Arkansas well into the twentieth century. Schools occasionally staged minstrel shows, with author Grif Stockley, for instance, recalling that his all-white high school in Marianna (Lee County) staged a blackface minstrel show in the 1960s, and such venues as the Kempner Theatre in Little Rock (Pulaski County) housed minstrel troupes during the early decades of the twentieth century.

For additional information:

Abbott, Lynn and Doug Seroff. Ragged but Right: Black Traveling Shows, “Coon Songs,” and the Dark Pathway to Blues and Jazz. Jackson: University Press of Mississippi, 2007.

Bean, Annemarie, James V. Hatch, and Brooks McNamara, eds. Inside the Minstrel Mask: Readings in Nineteenth-Century Blackface Minstrelsy. Hanover, NH: Wesleyan University Press, 1996.

Toll, Robert C. Blacking Up: The Minstrel Show in Nineteenth Century America. New York: Oxford University Press, 1974.

Matthew Mihalka

University of Arkansas, Fayetteville

Flippen, Jay C.

Flippen, Jay C. Minstrel Show

Minstrel Show  Minstrel Show Poster

Minstrel Show Poster  Minstrel Show Poster

Minstrel Show Poster

Comments

No comments on this entry yet.