calsfoundation@cals.org

Bathhouse Row

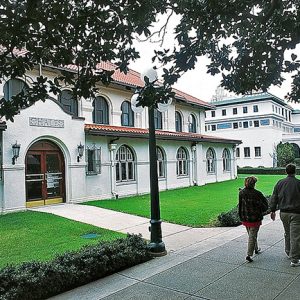

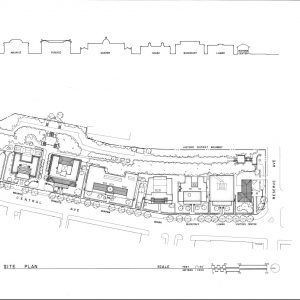

Bathhouse Row Historic District extends along the foot of the mountain that gives rise to the thermal springs in Hot Springs National Park. Located in downtown Hot Springs (Garland County), the scene is dominated by the most recent of a succession of bathing buildings dating back to 1830. Bathhouse Row includes eight surviving bathhouses: the Hale, Maurice, Buckstaff, Fordyce, Superior, Quapaw, Ozark, and Lamar. The landscape features sculptured fountains, water displays, and the Grand Promenade. Bathhouse Row has become the architectural core for downtown Hot Springs.

History

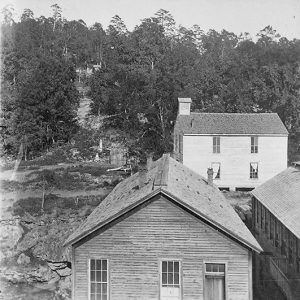

The first structures in the area to take advantage of the thermal springs were likely the sweat lodges of local Native Americans, which were followed by an unplanned conglomeration of buildings subject to fires, floods, and rot. At one time, the area was subject to numerous claims that eventually had to be settled by the U.S. Supreme Court. For eighty years, the government improved the spring area by containing the creek, filling and widening the narrow valley, and constructing the spa landscape. Ornate and numerous wooden bathhouses gave way to large and impressive masonry structures that represent the spa’s highest architectural attainment.

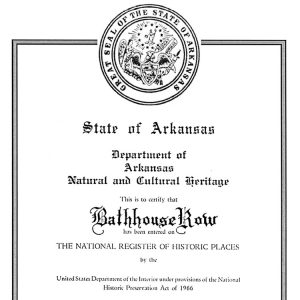

The peak of bathing came in 1946, when over one million baths were taken; however, a steady decline soon began. City redevelopment eliminated much of the moderate- to low-cost accommodations. The loss of other downtown businesses and the imposition of short-term bathhouse leases that reduced rather than encouraged maintenance also had an adverse affect. The placement of Bathhouse Row on the National Register of Historic Places in 1974, followed by its being made a National Historic Landmark in 1987, saved them but not the use of them. The Fordyce had already closed in 1962, after the decision to have only traditional bathing on the row; the Quapaw business declined, having previously enjoyed a highly successful bathing and physical therapy operation. A plan to use the Hale Bathhouse as a theater fell through, and the long-planned leasing of the Maurice by the Fine Arts Center was denied. The result is that the only bathhouses still operating are the venerable Buckstaff and Quapaw, and the only successful adaptively used building is the restored Fordyce Bathhouse Visitor Center and museum.

Descriptions

Plans for the most recent bathhouses envisioned a uniform architectural style, whereas business owners sought the business advantage of distinctive appearance. Little Rock (Pulaski County) architects George Mann and Eugene Stern designed several buildings, each unique. A common thread came from capitalizing on the legendary visit of the Spanish explorer Hernando de Soto to the springs. (Most historians now discredit the legend.) Mostly built in 1910s and 1920s era, design consideration had to take into account all perspectives adjacent to the formal entrance and the Maurice Historic Spring. In addition, the elevation of first floors for flood resistance called for basements, ramps, and steps while fireproofing the structures called for using brick (often veneered with stucco), sawed stone, concrete, marble, and tile. Long sunrooms and lobbies and great numbers of windows allowed ingenious manipulations to produce varied appearances and tasteful and artful qualities inside and out.

The oldest surviving bathhouse, the Hale, was constructed in 1892–93, replacing an earlier bathhouse. It was the first bathhouse with any modern conveniences. When the other bathhouses on Bathhouse Row were being built, it underwent extensive remodeling; a decade later, it was changed extensively, with drawbacks being the inclusion of wood and the exclusion of flood protection. The Hale came to have an abundance of arched windows, iron grills, and an elevation above the oak doors in the entryway. Its builders had its name carved in stone between dogwood blossoms in an effort to be distinctive. Its greatest distinction came from having a very large red tile hip roof magnified by a wide overhang with exposed beams. The Hale ceased operation in 1978. It was remodeled as a theater and concessionaire in 1981, but this venture lasted only nine months.

The Maurice, on the north side of the formal entrance, was designed by George Gleim Jr. of Chicago, Illinois, and was built in 1911–12. It set the tone for those to follow; a bronze and crystal fountain in a broad walkway, large windows in front, and a highly decorated lobby presented an open look. The stained glass below the skylight in the Roycroft Den was visible from the street, as were large patterned blue tile panels on the stucco façade. Bath halls had expanses of art glass featuring mermaids among lotus lilies. The game room sported a hunting scene around the perimeter. The green tiled roof signified closeness to nature. In 1931, a therapeutic pool was added in order to treat various forms of paralysis; the addition was inspired by treatments President Franklin D. Roosevelt received in Warm Springs, Georgia.

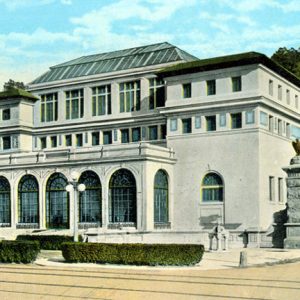

Completed in 1912, the Buckstaff conjures a Roman temple image with a story-and-a-half Doric colonnade topped by a wide flat pediment, all in white against the tan brick building. Arched lower-floor windows are ideally suited for striped awnings. Urn finials on the upper front complement the four planters on the open porch. Brass rails frame the ramp. The elimination of a sun porch in front allowed for an appearance of greater height. Sunbathing went to the roof.

The Fordyce on the south side of the formal entrance had a reputation as the most complete and luxurious bathhouse and as an impressive monument to the recovery of health of the owner, Colonel Samuel Fordyce, who believed the waters restored his health. Designed by Mann and Stern and built in 1914–15, it, along with the Maurice, attracted wealthier clientele. Constructed of two tones of brick in a lozenge pattern, the Fordyce features terra cotta window surrounds and balconies displaying hundreds of classical ornaments. The latter material went into surrounds of cherub fountains in the lobby, otherwise cased in marble, and into the life-sized statue of de Soto and an Indian maiden fountain in the men’s bath hall. Above that fountain but below the skylight in the interior courtyard is the mythical Neptune and ladies in a sea of stained glass. The bronze and glass, chain-suspended marquis had a blue glass top so as to present a blue sky whether it was rainy or sunny. Like many of its neighbors, it has a red tile roof over part of a skylight. The gymnasium has a full hip roof.

The northernmost bathhouse, the red brick Superior, was designed by Hot Springs architect Harvey C. Schwebke and completed in 1916 on the site of an earlier Superior Bathhouse. It has a closed sun porch. The columns that frame the windows have white hobnail studs, while the windows have green frames. Upper-floor windows have green frames, green rimmed medallions, and the name of the bathhouse once appeared through windows in green neon script. The owners relied on reputation for service rather than unusual architecture. In 1923, it was damaged by a flood, though not extensively. In 1983, the Superior closed, and its furnishings were sold at auction.

The Quapaw acquired its name from the discovery of Indian artifacts during the excavation of the basement, which accounts for the Indian cartouche on the undulating pediment on the façade. Completed in 1922, it was a moderately priced bathhouse with none of the extras that others featured, such as beauty parlors. Along with the Ozark, it had bathing facilities on the first floor to accommodate the elderly and handicapped. Sculpins (a kind of fish) project from the seashell cartouches on companion pediments on the end bays. The front of the stucco building has archways and arched windows extending around the sides, and the sun porches have arched doors to interior spaces and rows of double arches in the ceiling. Vaulted stained glass extends the lengths of the bath halls. The enormous dome tower is the highest on Bathhouse Row and is topped with a copper cupola. The tiles zigzag around the top of the dome, and flying horse and Neptune heads alternate in a golden tile band at the base. Curved ramps lead to the entrance. The Quapaw closed as a bathhouse in 1984 but reopened in 2008.

The structure of the Ozark, which was also completed in 1922 and designed by Mann and Stern, is odd because it is next to a bend in the street. Side bays recede to the next tier, which in turn carries the effect to towers with red tiled roofs and copper finials. The square towers have arched openings on all sides, but all other windows are square and are single or double receded. Urns rest on the ends of the second floor. The façade planters each have pairs of mythical flying animals. Tree of Life medallions are near the entrance. The Ozark closed in 1977.

The Lamar copies many elements of stucco building then popular in California. Finished in 1923, it features downward-pointing blue tile panels that accent the sun porch, which extends over nearly the full width. The Chicago windows in a modified arch have three panes. Square blue tile panels accent the upper floor. Two planters are on the bases of ascending pedestals at the front walk. Tile wall caps are on the roof and the pediment above the entry door. The Lamar ceased operations in 1985.

The Visitor Center, constructed in 1936, is now known simply as the administration building. Its predecessor fronted on the row and was sometimes mistaken for a bathhouse. The remedy for this confusion was to face the new edifice on the adjacent street. The Spanish style, by this time, had become thoroughly ingrained, hence the large brown double oak doors, iron grills, iron balcony rails, and red-tiled hip roof with an exposed beam overhang. The massive stone entrance surrounds jutting above the first floor emphasized form over design.

The ultimate landscape emerged when the second Arlington Hotel burned on April 5, 1923, and its site became a lawn. A park maintenance shop, cooling towers, the Government Free Bathhouse, and the Imperial Bathhouse were razed, and a service road closed, making the Grand Promenade a reality and giving rise to present-day downtown Hot Springs.

The Fordyce bathhouse, which has served as the Visitor Center and museum since 1989, closed temporarily in October 2012 for structural repairs and improvements; it reopened in 2014.

For additional information:

“Bathhouse Row.” National Register of Historic Places nomination form. On file at Arkansas Historic Preservation Program, Little Rock, Arkansas.

Carpenter, Kathryn Blair. “Access to Nature, Access to Health: The Government Free Bathhouse at Hot Springs National Park, 1877–1922.” MA thesis, University of Missouri–Kansas City, 2019.

Carroll, D. P. Bathhouse Row: We Bathe the World. Hot Springs, AR: Matter of Time Publishing, 2008.

Hanor, Jeffrey S. Fire in Folded Rocks. Hot Springs, AR: Eastern National Parks and Monuments Association, 2003.

“History: The Past is Where the Fun Is.” Hot Springs, Arkansas. https://www.hotsprings.org/pages/history/ (accessed July 11, 2023).

Hot Springs National Park (National Park Service). http://www.nps.gov/hosp (accessed July 11, 2023).

Shugart, Sharon. The Hot Springs of Arkansas through the Years. Hot Springs, AR: Eastern National Parks and Monuments Association, 1996.

———. “‘What’s a Nice Set of Springs Like You Doing in a Place Like This?’ The Bathhouses at the Hot Springs of Arkansas, 1809–1878.” The Record 44 (2013): 3.1–3.36.

Earl Adams

National Park Service

Bill Norman

Crossett, Arkansas

Bathhouse Row

Bathhouse Row  Bathhouse Row; 1867

Bathhouse Row; 1867  Buckstaff Bathhouse

Buckstaff Bathhouse  Bathhouse Row

Bathhouse Row  Bathhouse Row Certification Document

Bathhouse Row Certification Document  Bathhouse Row Plan

Bathhouse Row Plan  Buckstaff Bathhouse Facilities

Buckstaff Bathhouse Facilities  De Soto Sculpture

De Soto Sculpture  Early Bathhouses

Early Bathhouses  Fordyce Bathhouse

Fordyce Bathhouse  Hale Bath House

Hale Bath House  Hale Bathhouse

Hale Bathhouse  Hale Bathhouse

Hale Bathhouse  Hot Springs, Early Nineteenth Century

Hot Springs, Early Nineteenth Century  Huffman Hamilton Bathhouse

Huffman Hamilton Bathhouse  Imperial Bathhouse

Imperial Bathhouse  Lamar Bathhouse

Lamar Bathhouse  Maurice Bath House

Maurice Bath House  Maurice Bathhouse

Maurice Bathhouse  William Maurice Caricature

William Maurice Caricature  Ozark Bathhouse

Ozark Bathhouse  Pythian Bathhouse

Pythian Bathhouse  Quapaw Bathhouse

Quapaw Bathhouse  Superior Bathhouse

Superior Bathhouse  Water Troughs

Water Troughs

Comments

No comments on this entry yet.