calsfoundation@cals.org

Carrie Amelia Moore Nation (1846–1911)

aka: Carry Nation

Carry Amelia Moore Nation was a temperance advocate famous for being so vehemently against alcohol that she would use hatchets to smash any place that sold it. She spent most of her life in Kansas, Kentucky, and Missouri, but she lived in Arkansas for several years near the end of her life; her last speech was in Eureka Springs (Carroll County). The house she lived in, which is in Eureka Springs, was made into a museum called Hatchet Hall for a time, then turned back into a private residence.

Carry Moore, whose first name is sometimes spelled Carrie, was born on November 25, 1846, in Garrard County, Kentucky, to George and Mary Moore. George Moore was of Irish descent, and he owned a plantation with slaves. Mary Moore had a mental illness that caused her to be under the delusion that she was a lady-in-waiting to the queen of England, and later she imagined that she actually was the queen. Despite this, she was the mother to six children, including Carry.

Moore grew up under the care of her father’s slaves. She was close to one of the slaves, named Aunt Eliza. It was not until Moore was older that she was allowed to eat at the same table as her parents because her mother believed that being with the slaves was the best way to bring up her children.

When the Civil War began, the family moved to Texas, and on the way, they stopped near the Pea Ridge battlefield in Benton County. Moore was sickly at the time.

She married a doctor named Charles Gloyd on November 21, 1867. Her parents did not approve of the marriage because they knew that Gloyd was an alcoholic, though she did not know about his drinking problem until after they were married. Their marriage was unhappy, especially since their only child, a girl they named Charlien, had a mental disability. Carry Gloyd believed it was caused by her husband’s drinking. She left him, and he died only months later.

Her second husband was David Nation, an editor of a newspaper and a part-time preacher and lawyer. Their marriage was not happy either, because they argued about religion. She believed in helping needy people by taking them in, even when it inconvenienced her husband and stepchildren. David Nation was asked to resign as preacher of his church because his wife stirred up trouble. In 1877, the Nation family moved to Texas, although Carry Nation did not want to go. The couple divorced in 1901, not having had any children.

During this time, Nation had already been speaking against tobacco and alcohol. She especially disliked alcohol, most likely because of her experience with her first husband. She referred to alcohol as evil spirits. On one occasion, at a store owned by a man known as O. L. Day, she rolled a keg of whiskey onto the street, opened it with a hatchet, and set it on fire. She would go into any place that sold any kind of alcohol, even for medical purposes, and get rid of it. She broke windows and mirrors as well as destroyed kegs of beer or whiskey with her hatchets. At times, she attacked the people who sold the alcohol.

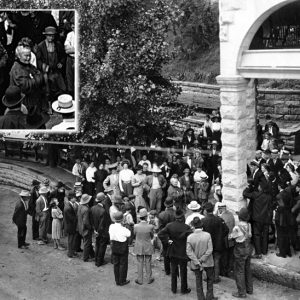

Nation was arrested many times in several states, including Oklahoma, Kansas, and Missouri. She spent time in the Little Rock (Pulaski County) jail, and she was arrested in Hot Springs (Garland County) in the winter of 1907. She was released when she made a deal with the mayor to speak at the opening of a new subdivision, for which he paid her fifty dollars. She made an additional sixty dollars selling souvenir hatchets. In Little Rock in 1906, she took a tour of twenty-six saloons and bars. She made speeches, and many people admired her. Some followed her on her travels and helped her smash saloons and bars, but she also made a lot of enemies, some of whom threw eggs at her.

Nation’s daughter, Charlien, was committed to the Texas State Lunatic Asylum in 1905. Nation tried to move her to Austin, Texas, and then to Oklahoma, but she finally brought her to Hot Springs, where Charlien stayed for only a few years.

When Nation wrote her autobiography, The Use and Need of the Life of Carry A. Nation, at the age of sixty, she was living in Oklahoma, and she wrote that she planned to stay there. However, not long after that, she bought her home in Eureka Springs. She wanted a quiet place to live, and she said that Arkansas reminded her of Scotland, where she had recently traveled. In the time she lived there, the house was both a boarding house and a school. She did most of the cooking herself and provided religious instruction for her boarders. The school was founded in 1910 and was called “National College” although it did not offer classes at a college level. Although she continued to travel, she owned the house until her death.

Her final speech was in Eureka Springs on January 13, 1911. She had recently had health problems, but the speech had been going well. Suddenly she stopped and gasped out, “I have done what I could.” Then she lapsed into a coma. She was taken to Evergreen Place Hospital in Kansas, where she remained in poor condition until her death on June 9, 1911. Doctors said the cause of death was paresis.

She is buried in Belton, Missouri. Her grave was unmarked for many years until the Woman’s Christian Temperance Union (WCTU), of which she had been a member, erected a gravestone with her name and the quote: “Faithful to the Cause, She Hath Done What She Could.”

A fountain was built in her honor in Wichita, Kansas, not far from the place of one of her first acts against alcohol. The fountain was destroyed only a few years later when the driver of a beer truck lost control and ran into it.

If Nation had lived just a few years longer, she could have seen Prohibition become the law of the land. She was not the only temperance advocate, but she was probably one of the most influential. The house that became known as Hatchet Hall still stands in Eureka Springs. Nearby is a spring named after Nation.

For additional information:

Beals, Carleton. Cyclone Carry: The Story of Carry Nation. Philadelphia: Chilton Company, 1962.

“Carry A. Nation: The Famous and Original Bar Room Smasher.” Kansas State Historical Society. http://www.kshs.org/exhibits/carry/carry1.htm (accessed June 3, 2022).

Grace, Fran. Carry A. Nation: Retelling the Life. Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 2001.

Lewis, Bill. “Carry Nation: The Trouble Was All in Her Head.” Arkansas Gazette. August 25, 1978, pp. 1B, 6B.

Nation, Carrie. “The Use and Need of the Life of Carry A. Nation” http://www.druglibrary.org/schaffer/history/e1900/cn/index.htm (accessed June 3, 2022).

Taylor, Robert Lewis. Vessel of Wrath: The Life and Times of Carry Nation. New York: New American Library, Inc., 1966.

Anastasia Teske

North Little Rock, Arkansas

Hatchet Hall

Hatchet Hall  Carrie Nation

Carrie Nation  Carrie Nation

Carrie Nation  Carrie Nation

Carrie Nation

Carrie Nation was related to my mother and to my grandmother, Marjorie Moore. She told me Carrie was my great-grandmother.