calsfoundation@cals.org

Fort Chaffee

aka: Camp Chaffee

Fort Chaffee, just outside of Fort Smith (Sebastian County) and Barling (Sebastian County) on Arkansas Highway 22, has served the United States as an army training camp, a prisoner of war camp, and a refugee camp. Currently, 66,000 acres are used by the Arkansas National Guard as a training facility, with the Arkansas Air National Guard using the fort’s Razorback Range for target practice.

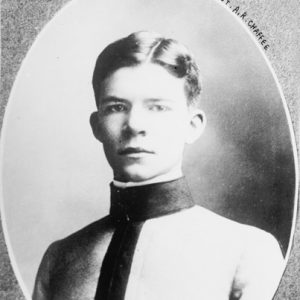

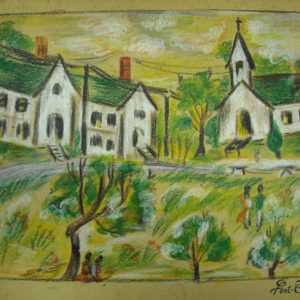

Groundbreaking for what was then Camp Chaffee was held on September 20, 1941, as part of the Department of War’s preparations to double the size of the U.S. Army in the face of imminent war. That month, the United States government paid $1.35 million to acquire 15,163 acres from 712 property owners, including families, farms, businesses, churches, schools, and other government agencies. The camp was named after Major General Adna R. Chaffee Jr., an artillery officer who, in Europe during World War I, determined that the cavalry was outmoded and, unlike other cavalry officers, advocated for the use of tanks. It took only sixteen months to build the entire base. The first soldiers arrived on December 7, 1941, the day the Japanese bombed Pearl Harbor, Hawaii. The installation was activated on March 27, 1942. From 1942 to 1946, the Sixth, Fourteenth, and Sixteenth Armored Divisions trained there. During World War II, it served as both a training camp and a prisoner-of-war (POW) camp. The major purpose of the camp was to train soldiers for combat and prepare units for deployment, but from 1942 to 1946, there were also 3,000 German POWs there. The creation of the camp caused the nearby town of Barling to experience a tremendous boom in housing and businesses.

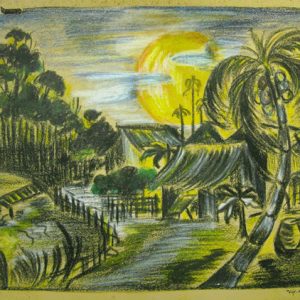

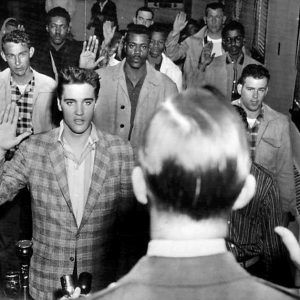

From 1948 to 1957, Chaffee was the home of the Fifth Armored Division. On March 21, 1956, Camp Chaffee was re-designated as Fort Chaffee; the army generally refers to something as a fort when it is a more permanent installation than a camp. In 1958, Chaffee was home to its most famous occupant, Elvis Presley. Presley received his first military haircut in Building 803. In 1959, the “Home of the U.S. Army Training Center, Field Artillery” moved from Fort Chaffee to Fort Sill, Oklahoma, where it remains. From 1960–61, the fort was the home of the 100th Infantry Division. In 1961, Fort Chaffee was declared inactive and placed on caretaker status, though it was reactivated again later that year and on several other occasions through 1974. During the Vietnam War, the fort was used as a test site for tactical defoliants like Agent Orange.

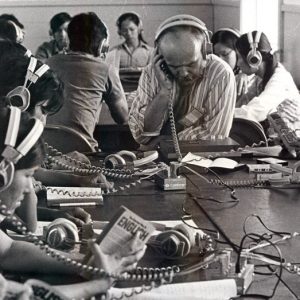

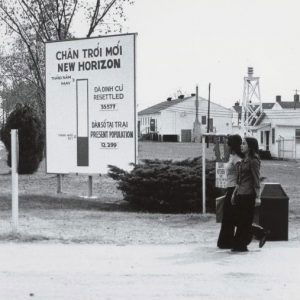

From 1975 to 1976, Fort Chaffee was a processing center for refugees from Southeast Asia. The facility processed 50,809 refugees of the Vietnam War, giving them medical screenings, matching them with sponsors, and arranging for their residence in the United States. On May 6, 1980, Chaffee became a Cuban refugee resettlement center after the Cuban government allowed American boats to pick up refugees at the port of Mariel. Three weeks later, a number of refugees rioted at Chaffee and burned two buildings. State troopers and tear gas were used to break up the crowd, and eighty-four Cubans were jailed. In two years, Fort Chaffee processed 25,390 Cuban refugees.

In 1987, the Joint Readiness Training Center began training soldiers at Chaffee. The center was transferred to Fort Polk, Louisiana, in 1993. In 1995, the Base Realignment and Closure Commission recommended the closure of Fort Chaffee. The recommendation was approved with the condition that minimum essential ranges, facilities, and training areas were maintained as a Reserve Component Training enclave. On September 28, 1995, Fort Chaffee became a subinstallation of Fort Sill. In late 1995, the federal government declared 7,192 of Fort Chaffee’s 76,075 acres to be surplus and turned the land over to the state. The remaining 66,000 acres were turned over to the Arkansas National Guard for use as a training facility.

A change-of-command ceremony was held on September 27, 1997. Command was transferred from the U.S. Army to the Arkansas Army National Guard when the U.S. Army garrison was deactivated, and Fort Chaffee became the Chaffee Maneuver Training Center for Light Combat Forces. The Fort Chaffee Redevelopment Authority was established to begin redeveloping the 6,000 acres that were turned over to the state. This was to include demolishing more than 700 buildings and rezoning land. The official redevelopment of the base began shortly after land was turned over, and the redevelopment authority is overseeing a number of residential, commercial, and industrial projects in what is known as Chaffee Crossing. On January 6, 2005, ground was broken for the Janet Huckabee Arkansas River Valley Nature Center, which now sits on 170 acres that was previously a part of Fort Chaffee.

With property transfers complete and minimal staff permanently stationed there, the Chaffee Maneuver Training Center was declared an open post. The gatehouses were abandoned, and most of the fencing was removed. Military Police patrols were discontinued, and emergency services turned over to the city of Barling, the Arkansas State Police, and Highway Patrol Troop H. This lasted until the September 11, 2001, terrorist attacks on the United States. Then, military installations were declared a closed post, and the center again took over emergency services. After Hurricane Katrina struck the Gulf Coast in 2005, the empty barracks at Fort Chaffee were converted into temporary housing for more than 10,000 refugees from Louisiana, Mississippi, Texas, and other areas affected by the hurricane and its aftermath.

Fort Chaffee has a rich military history, but it also has a bit of Hollywood history. In 1984, the movie A Soldier’s Story, starring Howard E. Rollins Jr. was shot at Fort Chaffee. Four years later, the Neil Simon movie Biloxi Blues, starring Matthew Broderick, was filmed there. The most recent visit from Hollywood was in 1995 for The Tuskegee Airmen with Laurence Fishburne and Cuba Gooding Jr.

For additional information:

Camp Chaffee Collection. Butler Center for Arkansas Studies. Central Arkansas Library System, Little Rock, Arkansas. Online at https://arstudies.contentdm.oclc.org/digital/search/searchterm/mss.02.12 (accessed January 7, 2026).

Chaffee Crossing. http://www.chaffeecrossing.com/ (accessed February 8, 2023).

“Fort Chaffee.” GlobalSecurity.org. http://www.globalsecurity.org/military/facility/fort-chaffee.htm (accessed February 8, 2023).

Froelich, Jacqueline. “During Vietnam, Agent Orange Got Arkansas Trial, Veterans and Locals Still Haunted by Exposure Fears.” Arkansas Public Media. http://arkansaspublicmedia.org/post/during-vietnam-agent-orange-got-arkansas-trial-veterans-and-locals-still-haunted-exposure-fears (accessed February 8, 2023).

Lipman, Jana K. “A Refugee Camp in America: Fort Chaffee and Vietnamese and Cuban Refugees, 1975–1982.” Journal of American Ethnic History 33 (Winter 2014): 57–87.

Maranda Radcliff

Fort Smith, Arkansas

Staff of the Encyclopedia of Arkansas History & Culture

My dad got a job in Fort Smith in 1961, and he and Mom and I moved to a trailer court across the street from the Branding Iron beer joint on Midland Boulevard. Dad often stopped at the Branding Iron on his way home from work. One night, he met two soldiers playing pool. Before long, Dad had sold the soldiers our house trailer, furniture and all, for about twice what he thought he had in it. He staggered home to tell Mom the good news, and she instantly burst into tears. Dad had come to town and started to work right away; he hadn’t had time to realize that Fort Chaffee had reactivated. Fort Smith was busting at the seams with new people, and there was no place to live. Some families were even living in their cars. Since we had to move in a week, the hunt for a house or apartment began, and Mom found absolutely nothing available. So, we moved to the Terry Motel a little farther down Midland next to the fairgrounds. It had been built in the 1950s, replacing an earlier tourist court and was pretty nice. But our family of three and a full-grown boxer dog took up about every inch of that small room. We lived there for three long months until Mom waited on the front steps of a rental house all day, finally catching the owner and agreeing to pay one year’s rent ($2,400) in advance, which ate up the “big killing” Dad had made. The Terry Motel still stands and is in good repair. But if I live to be 100, every time I pass the motel I’ll remember the look on my mother’s face, now going on fifty years ago, when Dad gave her his most excellent news.