calsfoundation@cals.org

Philander Smith University

Philander Smith University was the first historically Black, four-year college in Arkansas and the first historically Black college to be accredited by a regional accrediting institution.

Like most of the African American colleges and universities in the United States, Philander Smith University originated in the Bureau of Refugees, Freedmen and Abandoned Lands (commonly known as the Freedmen’s Bureau). The War Department organized the Freedmen’s Bureau on March 3, 1865, just before the Civil War ended. Throughout its six-year existence, the bureau sold confiscated properties and raised money to help the freed slaves gain access to the rights that they were denied during slavery. Among these was the right to be educated.

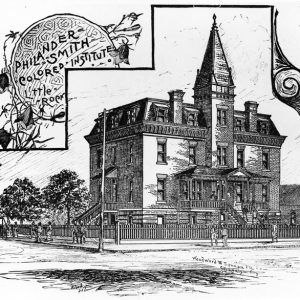

In 1869, the bureau directed that schools be made available to Black Arkansans. On November 7, 1877, the future Philander Smith College began as Walden Seminary in Little Rock (Pulaski County). Named for bureau activist John Walden (1831–1914) and located in the Wesley Chapel Methodist Church at 8th Street and Broadway, the seminary was designed to educate Black ministers. Reverend Thomas Mason, its first president (serving from November 1881 to May 1897), moved the school in 1882 to a new campus at 11th and Izard streets.

This move was made possible by a public plea for gifts to the school. Responding to an article published in the Christian Advocate in 1882, Adeline Smith of Oak Park, Illinois—the widow of Philander Smith, “a liberal giver to Asiatic Missions” with an “interest in the work of the church in the South”—donated $10,500 to Walden Seminary. The seminary was promptly renamed Philander Smith College. On March 3, 1883, the state chartered it as a four-year college.

By 1887, the college employed six faculty members and enrolled nearly 200 students of “various levels of ability.” From 1887 to 1891, money contributed by Little Rock residents and the Slater Fund for Negro Education made possible a building for instruction in printing and carpentry. Resisting the national trend of educating African Americans only in “practical” subjects, Philander Smith combined courses in journalism and advertising composition with vocational classes. While it offered elementary and secondary classes, the school’s charter emphasized that it was to be a four-year college, and it offered both BA and BS degrees. In 1888, Philander Smith conferred its first bachelor’s degree on Rufus C. Childress, who later became assistant supervisor of Arkansas’s Black schools.

In the late 1880s and the 1890s, the college offered “classical” and “scientific” degrees with courses in Greek, Latin, algebra, and natural philosophy. Moral and religious education, including prayer meetings and Bible studies, was required. Tuition was free for pre-ministerial students and a dollar a month for everyone else.

In 1896, with 268 students enrolled at the college, Mason resigned amid dissent about the employment of white faculty. At the time, Philander Smith then had eleven white teachers and four Black teachers on its faculty. As early as 1883, students and community leaders had debated the college’s hiring of both Black and white teachers. By the turn of the century, America’s ninety-five Black colleges were actively debating whether liberal arts courses or vocational programs were more appropriate for Black students. Black faculty also demanded “greater control of their schools. Many Blacks began to question why, in the wake of an increasingly educated population, more African Americans were not being appointed to tenured faculty positions and high-ranking administrative jobs,” according to Juan Williams and Dwayne Ashley.

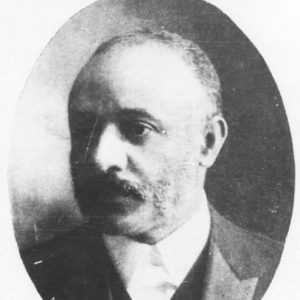

Mason’s successor, Rev. James Monroe Cox, served Philander Smith for thirty-eight years—as a professor of classical languages for eleven years and as president for twenty-seven years—until 1924. Seven years into the Cox presidency, Philander Smith employed for the first time an all-Black faculty. Cox emphasized the liberal arts and dropped the grammar school in 1923. The campus’s Cox Administration Building is named for him.

George Collins Taylor, president of Philander Smith from 1924 to 1936, was a Philander Smith graduate. During his presidency, fewer than one in ten Black Southern youths attended high school, yet in 1932, Philander Smith College awarded twenty-two degrees, demonstrating its success as a four-year college. To place a greater emphasis on the mission of Philander Smith in educating students at the college level, Taylor eliminated the secondary school department.

When Marquis LaFayette Harris became president in 1936, the college had a $200 endowment. Philander benefited in 1939 when the Methodist Church united its various groups that had been divided regionally since the mid-nineteenth century. This union, known since 1968 as the United Methodist Church, provided a broader base of support for the school, and endowments grew dramatically. Under Harris, the school bought the campus of Little Rock Junior College from the Little Rock School Board in July 1948. Earlier, Philander Smith opened a program in flight instruction and maintenance for the war effort in 1942. Throughout the 1940s, Philander added business and science classes and offered night school classes for returning veterans. In 1944, the school became a founding member of the United Negro College Fund. In 1949, it was the state’s only private Black college with North Central Association of Colleges and Schools accreditation.

In the 1950s, Harris approved construction of a president’s residence, a science building, and new dormitories. By the late 1950s, Philander Smith employed forty-six faculty members and had a $500,000 endowment. The Harris Library and Fine Arts Auditorium is named for Harris. In May 1955, Philander Smith College became the first predominantly Black school in Arkansas to grant a bachelor’s degree to a white student, Dorothy Martin.

In the final years of Harris’s presidency, Philander Smith College—a small, quiet, religious school—entered a tumultuous era. Students and faculty of the college were not noticeably involved in Little Rock’s Central High School desegregation crisis. In 1959, however, Harris, who had directed Philander Smith students to see movies or shop in downtown Little Rock only in groups, learned that Philander Smith students had been arrested during a sit-in at a white business. Although Harris wished to expel the students, other administrators of the school persuaded him to allow them to remain enrolled without any penalty. (Rumors that some of these students lost financial aid from the school cannot be confirmed.)

On campus, the 1960s brought a series of presidents to the college: James D. Scott (1960–1961), Roosevelt Crockett (1961–1965), and Ernest Dixon (1965–1969). Off campus, Philander Smith students negotiated a January 1, 1963, agreement with downtown Little Rock merchants to desegregate public transportation and facilities and conducted peaceful but public demonstrations at the Arkansas State Capitol after the 1968 assassination of Dr. Martin Luther King Jr.

With the end of segregated higher education, Black colleges had to deal with cultural identity issues. Desegregation had a paradoxical effect on the institutions that had trained the Black intellectuals who dismantled the Jim Crow system. Williams and Ashley wrote that “between 1976 and 1994 predominantly white colleges experienced a forty-percent increase in Black enrollment; [historically Black institutions] increased by only half that amount.” Lower endowments for Black colleges, seen as “a direct result of the wide income gap between African Americans and whites,” put huge financial pressure on small private Black colleges. The relevance of historically Black schools was questioned, although, as of the beginning of the twenty-first century, a third of all bachelor’s degrees awarded to African Americans come from historically Black institutions. Seventy percent of the nation’s Black physicians and dentists, as well as half of all Black engineers are educated at historically Black institutions.

Presidents Walter Hazzard (1969–1979), Grant Shockley (1979–1983), and Hazo Carter (1983–1987) worked to ensure Philander’s future with improvements to classrooms, student housing, and academic programs. Meyer Titus, president from 1988 to 1998, raised $2 million to build a multi-purpose academic center (named the Titus Building) and a business classroom and gymnasium complex on the campus. From 1998 to 2004, Trudie Kibbe Reed, Philander’s first female president, instituted an Honors Academy and a Black Family Studies program. Reed increased the college endowment to $9 million and raised $37.6 million to construct three state-of-the-art facilities: the Kendall Health Mission Center for health sciences education, a new dormitory complex, and the Reynolds Library and Technology Center. Dr. Walter Kimbrough assumed the duties of president in December 2004. He was named president of Dillard University in New Orleans, Louisiana, in late 2011. His successor, Johnny Moore—a 1989 Philander Smith graduate—was selected as the college’s new president in April 2012. Moore resigned in February 2014 and was replaced by Roderick Smothers. Philander’s Social Justice Institute opened on campus in 2017. Smothers resigned in May 2023, with Board of Trustees chair Terry Espen serving as the executive in charge until a nationwide search could be held to select a new president.

In spite of the challenges faced by all schools entering the twenty-first century, Philander Smith has continued to grow in size and in reputation. The faculty and the student body of the college remain predominately Black. Notable graduates of Philander Smith include Dr. Joycelyn Elders, former U.S. surgeon general; Rev. James H. Cone, professor at Union Theological Seminary in New York; Lottie Shackelford, Little Rock’s first woman mayor; and professional athletes Elijah Pitts and Hubert “Geese” Ausbie. More than forty percent of Philander Smith’s students are first-generation college students.

In 2023, Philander Smith began offering its first graduate degree, a Master of Business Administration. That same year, it announced the establishment of a community engagement center, located on West 12th Street, including office space for its Social Justice Hub, criminal justice and cybersecurity program, and Community Development Corporation. Also announced was a change in name from Philander Smith College to Philander Smith University.

In fall 2024, enrollment was 1,000 students.

For additional information:

Gibson, De Lois. “A Historical Study of Philander Smith College, 1877 to 1969.” EdD thesis, University of Arkansas, 1972.

Philander Smith College Yearbooks. Butler Center for Arkansas Studies. Central Arkansas Library System, Little Rock, Arkansas (accessed September 13, 2024).

Philander Smith University. http://www.philander.edu (accessed September 13, 2024).

“Philander Smith Opens Help Center.” Arkansas Democrat-Gazette, May 6, 2023, 8B. Online at https://www.arkansasonline.com/news/2023/may/07/philander-smith-college-opens-help-center/ (accessed September 13, 2024).

Williams, Juan, and Dwayne Ashley. I’ll Find a Way or Make One: A Tribute to Historically Black Colleges and Universities. New York: Amistad/HarperCollins Publishers, 2004.

Kae Chatman

Little Rock, Arkansas

Staff of the CALS Encyclopedia of Arkansas

Arkansas Council on Human Relations (ACHR)

Arkansas Council on Human Relations (ACHR) Arkansas' Independent Colleges and Universities

Arkansas' Independent Colleges and Universities Carter, Vertie Lee Glasgow

Carter, Vertie Lee Glasgow Education, Higher

Education, Higher Iggers, Georg

Iggers, Georg Williams, Robert Lee, II

Williams, Robert Lee, II Campus Center

Campus Center  James M. Cox

James M. Cox  Elders School of Allied and Public Health

Elders School of Allied and Public Health  Mabee Kresge Science Hall

Mabee Kresge Science Hall  Ottenheimer Business Center

Ottenheimer Business Center  The Panther

The Panther  Philander Smith College

Philander Smith College  Philander Smith College

Philander Smith College  Philander Smith Colored Institute

Philander Smith Colored Institute  Philander Smith Graduates

Philander Smith Graduates  The Philanderian

The Philanderian  Titus Academic Center

Titus Academic Center  U. M. Rose School

U. M. Rose School

Comments

No comments on this entry yet.