calsfoundation@cals.org

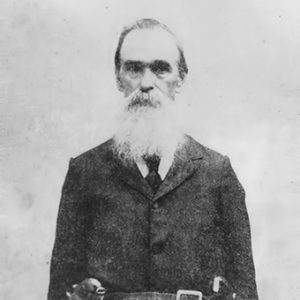

Isaac Charles Parker (1838–1896)

Isaac Charles Parker served as federal judge for the Federal Court of the Western District of Arkansas in Fort Smith (Sebastian County). He tried 13,490 cases, with 9,454 of them resulting in guilty pleas or convictions. His court was unique in the fact that he had jurisdiction over all of Indian Territory, covering over 74,000 square miles. He sentenced 160 people to death, including four women. Of those sentenced to death under Parker, seventy-nine men were executed on the gallows.

Born on October 15, 1838, in Barnesville, Ohio, Isaac Parker was the son of Joseph and Jane Parker. Joseph was a farmer, and Jane was known for her strong mental qualities and business habits. She was active in the Methodist church, and Parker attributed his success to the way he was raised, especially in connection with his mother. He was the great-nephew of Governor Wilson Shannon and attended Breeze Hill Primary School when he was not needed on the farm. Once he completed his primary education, he attended Barnesville Classical Institute, a private school. Parker taught in a country primary school to pay for his higher education.

At seventeen, Parker decided to study law. He became an apprentice, working under a Barnesville lawyer, and studied on his own, passing the bar in 1859. He began his legal career with his uncle, D. E. Shannon, in St. Joseph, Missouri, at the Shannon and Branch law firm, and by 1861, he was operating on his own. It was during this time that he met his wife, Mary O’Toole, whom he married on December 12, 1861. He won election as the city attorney on the Democratic ticket in April 1861, but he had been in office only a few days when the Civil War broke out, causing him to re-evaluate his political beliefs. He enlisted in the Sixty-first Missouri Emergency Regiment, a home guard unit for the Union forces.

Parker ran for county prosecutor of the Ninth Missouri Judicial District on the Republican ticket, making his break from the Democratic Party official. He also served as a member of the Electoral College (he cast his vote for Abraham Lincoln) in the election of 1864. He served two terms in the U.S. Congress, being elected in 1870 and 1872. While in Congress, he assisted veterans of his district in securing pensions, lobbied for construction of a new federal building in St. Joseph, sponsored legislation that would have allowed women the right to vote and hold public office in U.S. territories, and also sponsored legislation that would have organized the Indian Territory under a formal territorial government. It was during his second term that his speeches supporting the Bureau of Indian Affairs received national attention. During his second term in Congress, he put most of his effort into Indian policy and the fair treatment of the tribes that were living in the Indian Territory. It was after his second term in Congress that he began to seek a presidential appointment as judge of the Western District of Arkansas in Fort Smith. On March 18, 1875, President Ulysses S. Grant appointed him to the position.

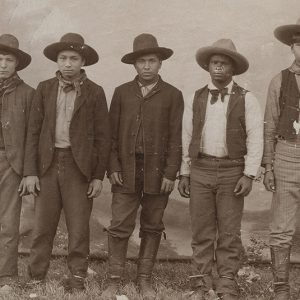

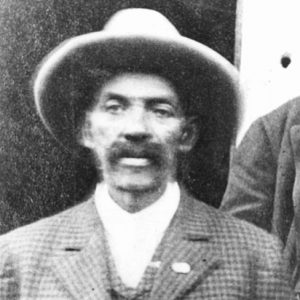

Parker became the federal judge for the Western District of Arkansas, which had jurisdiction over Indian Territory. This court had moved to Fort Smith. In 1875, Bass Reeves was hired as a commissioned deputy U.S. marshal, making him one of the first Black federal lawmen west of the Mississippi River.

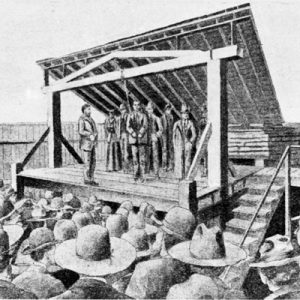

Parker arrived in Fort Smith on May 4, 1875, and held court for the first time on May 10, 1875. During his first term, he found eight men guilty of murder. Six of them died on September 3, 1875, on the gallows at Fort Smith. Parker’s court was supposed to hold four terms each year—in February, May, August, and November—but the caseload for the court was so large that the four terms ran together. Parker held court six days a week, each day often lasting up to ten hours each, in order to try as many cases as possible.

On November 9, 1882, Belle and Sam Starr were charged in the U.S. Commissioner’s Court at Fort Smith with the larceny of two horses. On March 8, 1883, a jury returned a guilty verdict, and Judge Parker sentenced the Starrs to a year in prison.

In 1883, Congress made cuts to jurisdiction areas. Jurisdiction over some portions of the Indian Territory was given to federal courts in Texas and Kansas, providing some relief to Parker’s court. There was, however, a continuous stream of settlers into the Indian Territory, over which he still had jurisdiction, and the crime rate increased.

Over the years, Parker became very involved in the community of Fort Smith. At his urging, the government gave the majority of the 300-acre military reservation to the city in 1884 to fund the public school system. He also served many positions besides judge in the community, including serving as the first board president of St. John’s Hospital (later known as Sparks Regional Medical Center and then Baptist Health-Fort Smith), and he was active on the school board. Mary, his wife, was also involved in many different social activities, and their sons, James and Charles, attended the public school which their father had helped to establish.

There was more to Parker’s position than sitting in a courtroom trying cases. He was occasionally called to testify in front of Congress or substitute for other federal judges in the area. He was also responsible for hearing more than just capital cases. He tried several civil cases during his time in Fort Smith as well.

Another change came about on February 6, 1889, when Congress took the circuit court authority from the federal court at Fort Smith and allowed the U.S. Supreme Court to begin reviewing all capital crimes. The latter went into effect on May 1, 1889, and had a very pronounced affect on Parker. Until this time, the president was the only person with the power to commute sentences; however, now the Supreme Court could overturn cases as well. A month after the Supreme Court’s review, Congress passed yet another act, the Courts Act of 1889, which established a federal court system in the Indian Territory, again decreasing the size of Parker’s jurisdiction. The Supreme Court began to reverse the capital crimes tried in Fort Smith, and two-thirds of the cases that were appealed were sent back to Fort Smith for a new trial.

Parker is often called the “Hanging Judge.” This alias is even alluded to in history books. At the time, capital offenses of rape and murder were punishable by death. However, it was not for the judge to decide guilt. Determining guilt was left up to the jury. Parker actually had no say in whether a person was to be hanged; in an interview published on September 1, 1896, in the St Louis Republic, Parker is quoted as saying, “I never hung a man. It is the law.” He, in fact, was against capital punishment, adding, “I favor the abolition of capital punishment, too. Provided that there is a certainty of punishment, whatever that punishment may be. In the uncertainty of punishment following crime lies the weakness of our ‘halting crime.’” His court did, however, sentence some of the most notorious outlaws to hang. Outlaws such as Cherokee Bill, Colorado Bill, and the Rufus Buck Gang are some of the well known who were sentenced to death and executed during Parker’s tenure.

On September 1, 1896, another act went into effect, removing the last of Parker’s Indian Territory jurisdiction. When the August 1896 term began, however, Parker was too ill to preside. Reporters interviewing Parker about the end of his jurisdiction over Indian Territory had to do so at his bedside. Parker died on November 17, 1896, of numerous health problems, including degeneration of the heart and Bright’s Disease. He is buried in the Fort Smith National Cemetery, only blocks from where he once presided as judge. His courtroom is now the Fort Smith National Historic Site.

For additional information:

Atkins, Jerry. Hangin’ Times in Fort Smith: A History of Executions in Judge Parker’s Court. Little Rock: Butler Center Books, 2012.

Brodhead, Michael J. Isaac C. Parker: Federal Justice on the Frontier. The Oklahoma Western Biographies 20. Norman: University of Oklahoma Press, 2003.

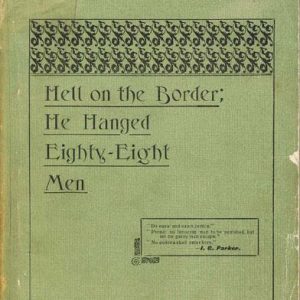

Harman, S. W. Hell on the Border: He Hanged Eighty Eight Men. Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 1992.

Stolberg, Mary M. “Politician, Populist, Reformer: A Reexamination of ‘Hanging Judge’ Isaac C. Parker.” Arkansas Historical Quarterly 47 (Spring 1988): 3–28.

Tuller, Roger. ‘Let No Guilty Man Escape’: A Judicial Biography of Isaac C. Parker. Norman: University of Oklahoma Press, 2001.

Underhill, Lonnie E. “The Hanging Judge: Isaac C. Parker, 1875–1896.” Journal of the West 61 (Fall 2022): 56–63.

Maranda Radcliff

Fort Smith, Arkansas

Hell on the Border

Hell on the Border Law

Law Post-Reconstruction through the Gilded Age, 1875 through 1900

Post-Reconstruction through the Gilded Age, 1875 through 1900 Rufus Buck Gang

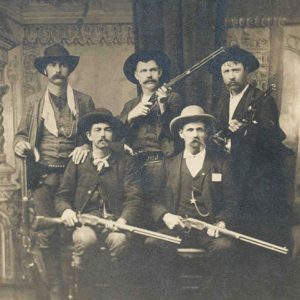

Rufus Buck Gang  Ned Christie Posse

Ned Christie Posse  Fort Smith Courthouses, 1896

Fort Smith Courthouses, 1896  Fort Smith Hanging

Fort Smith Hanging  Fort Smith National Historic Site

Fort Smith National Historic Site  Hell on The Border

Hell on The Border  George Maledon

George Maledon  Evett Dumas Nix

Evett Dumas Nix  Isaac Parker

Isaac Parker  Judge Isaac Parker

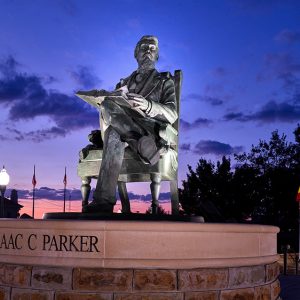

Judge Isaac Parker  Judge Parker Statue

Judge Parker Statue  Bass Reeves

Bass Reeves  Belle Starr

Belle Starr  U.S. Courtroom at Fort Smith

U.S. Courtroom at Fort Smith

Comments

No comments on this entry yet.