calsfoundation@cals.org

Hattie Caraway (1878–1950)

Hattie Ophelia Wyatt Caraway was the first woman elected to the U.S. Senate, the first woman to preside over the Senate, the first to chair a Senate committee, and the first to preside over a Senate hearing. She served from 1931 to 1945 and was a strong supporter of President Franklin D. Roosevelt’s economic recovery legislation during the Great Depression.

Hattie Wyatt was born to William Carroll Wyatt and Lucy Burch Wyatt on February 1, 1878, near Bakersville, Tennessee. It is unknown how many siblings she had, though the 1900 Census shows four children living at her parents’ residence. When she was four, she moved with her family to Hustburg, Tennessee, where she helped on the family farm and in her father’s general store. She enrolled in Ebenezer College in Hustburg but later transferred to Dickson Normal College in Dickson, Tennessee, where she received a BA in 1896.

After working several years as a schoolteacher in Tennessee, Wyatt married Thaddeus (Thad) Horatius Caraway of Clay County, Arkansas, a fellow Dickson graduate, on February 5, 1902. They settled in Jonesboro (Craighead County). She focused on taking care of the home and raising their three sons while her husband practiced law and began his political career. After he was elected to the U.S. House of Representatives as a Democrat in 1912, the family moved to Maryland. He represented Arkansas in the House from March 4, 1913, until March 3, 1921. After campaigning on issues that grew out of World War I, Thaddeus Caraway won a Senate seat in 1920 and served in the Senate from March 4, 1921, until his unexpected death on November 6, 1931.

On November 13, 1931, Arkansas governor Harvey Parnell appointed Caraway to fill the vacancy caused by her husband’s death. She was sworn in on December 8, 1931, and was confirmed in a special election on January 12, 1932, thus becoming the first woman elected to the U.S. Senate. On May 9, 1932, she became the first woman to preside over the Senate (when the vice president, Charles Curtis, was resting). She surprised many by announcing her intention to run for reelection, as many had not expected her to do so. Caraway was reelected in 1932 after a campaign tour with Huey P. Long, the populist senator from Louisiana. Long was motivated by sympathy for Caraway’s being a widow as well as by his ambition to extend his influence into the home state of his rival, Senator Joseph Taylor Robinson. In 1938, Caraway ran for reelection against Congressman John L. McClellan, whose campaign slogan was “We need another man in the Senate,” and she won with the support of veterans, women, and union members. Caraway was defeated by J. William Fulbright in 1944. Her term ended on January 2, 1945.

Caraway spoke on the Senate floor so infrequently that she became known as Silent Hattie. She believed in speaking briefly with well-chosen words and stated that she did not want to waste the taxpayers’ money on printing speeches in the Congressional Record. However, she often voiced her opinions in committee meetings. Caraway became the first woman to chair a Senate committee when she served as chair of the Senate Committee on Enrolled Bills from 1933 to 1944. She also requested and was assigned to the Agriculture Committee because of the importance of farming in her state. The committee also governed flood control and the navigation of rivers, two issues very relevant to Arkansas.

A strong supporter of Roosevelt’s New Deal legislation, Caraway seconded his nomination for reelection at the 1936 Democratic National Convention. In a rare speech to the Senate on relief and work-relief appropriations on May 25, 1938, Caraway stated, “My philosophy of legislation, and really on life, is to be broad-minded enough to consider human relationships and the well-being of all the people as worthy of consideration, to realize that all human beings are entitled to earn, so far as possible, their daily bread, and to try to prevent the exploitation of the underprivileged.”

Occasionally Caraway did not support Roosevelt’s policies. Although she voiced her opinions about equality of human beings when it came to New Deal legislation, Caraway was a woman from the South, where commonly held political views did not always coincide with those of Roosevelt. In 1938, Caraway joined many southern senators in voting against anti–poll tax and anti-lynching legislation, both of which Caraway viewed as unconstitutional. She also opposed the repeal of Prohibition.

Caraway was instrumental in securing Camp Robinson, Fort Chaffee, two Japanese relocation centers at Jerome (Drew and Chicot counties) and Rohwer (Desha County), five air bases, defense ordnance plants, and aluminum factories in Arkansas during World War II. Caraway also worked for the Equal Nationality Treaty of 1934, which extended to women numerous nationality rights previously limited to men. In 1943, she became the first woman in the Senate to cosponsor the proposed Equal Rights Amendment.

After leaving the Senate, Caraway remained in Washington in other civil service positions. She served on the United States Employees’ Compensation Commission from 1945 to 1946 and on the Employees’ Compensation Appeals Board from 1946 until her death. Hattie Caraway suffered a stroke in January 1950 and died in Falls Church, Virginia, on December 21, 1950. She is buried next to her husband at Oaklawn Cemetery in Jonesboro.

For additional information:

Hattie Wyatt Caraway Papers. Special Collections. University of Arkansas Libraries, Fayetteville, Arkansas.

Hendricks, Nancy. Dear Mrs. Caraway, Dear Mr. Kays. N.p.: 2010.

———. “Legacies & Lunch: Hattie Caraway.” October 1, 2014. Central Arkansas Library System, Little Rock, Arkansas. Video online at Butler Center AV/AR Audio Video Collection: Nancy Hendricks Lecture (accessed July 1, 2021).

———. Senator Hattie Caraway: An Arkansas Legacy. Charleston, SC: History Press, 2013.Hodges, Kristin Diane. “Covering Caraway: Arkansas Reports on Hattie Caraway’s Ascent to the United States Senate.” MA thesis, University of Arkansas at Little Rock, 2013.

Hutchinson, Donna King. “The Not So Silent Hattie Caraway: The Management of Rhetorical Roles.” MA thesis, University of Arkansas, 2002.

Jacobi, Keli Coburn. “United States Senator Hattie W. Caraway: How a ‘Well-Behaved’ Woman of the South Made History, Why So Few Know about It, and Why We Should Care.” MA thesis, University of Louisiana at Monroe, 2012.

Kincaid, Diane, ed. Silent Hattie Speaks: The Personal Journal of Senator Hattie Caraway. Westport, CT: Greenwood Press, 1979.

Malone, David. Hattie and Huey: An Arkansas Tour. Fayetteville: University of Arkansas Press, 1989.

Pownell, Sharon. “Senator Hattie Caraway.” Craighead County Historical Quarterly 13 (Spring 1975): 3–10.

Towns, Stuart. “A Louisiana Medicine Show: The Kingfish Elects an Arkansas Senator.” Arkansas Historical Quarterly 25 (Summer 1966): 117–27.

Wilkerson Freeman, Sarah. “Senator Hattie Caraway (1878–1950): A Southern Stealth Feminist and Enigmatic Liberal.” In Arkansas Women: Their Lives and Times, edited by Cherisse Jones-Branch and Gary T. Edwards. Athens: University of Georgia Press, 2018.

Williams, Nancy A., ed. Arkansas Biography: A Collection of Notable Lives. Fayetteville: University of Arkansas Press, 2000.

Julienne Crawford

Arkansas History Commission and State Archives

Calvert Mansion

Calvert Mansion  Caraway and Kids

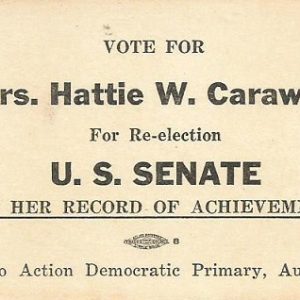

Caraway and Kids  Hattie Caraway Card

Hattie Caraway Card  Caraway Gravesite

Caraway Gravesite  Caraway Home

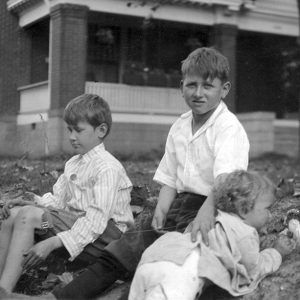

Caraway Home  Caraway Sons

Caraway Sons  Caraway Tribute

Caraway Tribute  Hattie Caraway

Hattie Caraway  Hattie and Thaddeus Caraway

Hattie and Thaddeus Caraway  Hattie Caraway Stamp Program

Hattie Caraway Stamp Program  Hattie Caraway Stamp

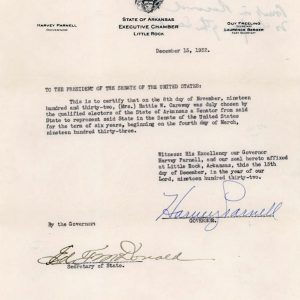

Hattie Caraway Stamp  Hattie Caraway Appointment Certificate

Hattie Caraway Appointment Certificate  Hattie Caraway

Hattie Caraway  Hattie Caraway and Granddaughter

Hattie Caraway and Granddaughter  Joe T. Robinson and Hattie Caraway

Joe T. Robinson and Hattie Caraway  Joe T. Robinson Portrait

Joe T. Robinson Portrait  Senators and Representative: 1938

Senators and Representative: 1938  Women of the 75th U.S. Congress

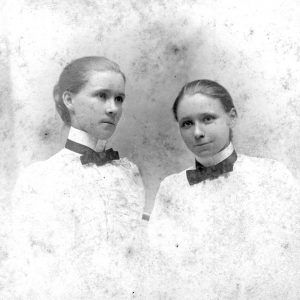

Women of the 75th U.S. Congress  Wyatt Sisters

Wyatt Sisters

Comments

No comments on this entry yet.